This season, Mardi Gras parades might not be rolling through the streets, but certain traditions will remain: King cake will still be enjoyed throughout the Carnival season, people will find smaller and safer ways to observe Mardi Gras practices, and the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club will continue the charity work that has fueled their organization for over 100 years.

The Zulu parade that rolls through the streets of New Orleans, on Mardi Gras morning, has long been a yearly routine for thousands of New Orleanians. As crowds gather and shout for one of the krewe’s famed painted coconuts, bands get revelers in the spirit and the enthusiasm of riders keeps the party going, as paraders cheer and chant for Zulu’s unique throws.

The krewe itself has a rich history dating back to the early 20th Century.

Inspired by a play he saw in 1908, John L. Metoyer founded the Zulu Organization in 1909 and crowned William Story as the first Zulu king. The group was officially incorporated as the Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club on Sept. 20, 1916.

Twenty-two group members signed the document which established bylaws, as well as the organization’s dedication to benevolence and goodwill. The majority of the men who belonged to Zulu were also involved in benevolent societies where, for a small yearly fee, Black people could seek financial aid for health care or the burial of deceased family members.

The Zulu King & Louis Armstrong

The krewe chooses its king via an election, and the official toast of king Zulu and queen Zulu takes place every year at Geddes and Moss Undertaking Co. on Washington Avenue. The funeral home has been a supporter of the Zulu organization since its inception.

“Zulu was fairly small when it all started,” said Charles Hamilton, a former Zulu king and organization president, who has been a member of Zulu since 1978 and has held other positions within the group.

“There weren’t many floats and there was no real route. The floats themselves were sponsored by bars. It wasn’t until 1949 when Louis Armstrong served as king Zulu and was on the cover of Life Magazine, that the krewe gained national prominence,” he said.

In the 1960s, membership in the Zulu organization dwindled to just 16 members, due to the pressure of local civil rights activists who saw the krewe as a type of mockery. Protesters printed a statement in the local Black community paper, The Louisiana Weekly, calling out the Zulu Parade as a caricature that portrayed Black people as uncivilized. The group publicly called for a boycott of the Zulu Parade.

In response, the Zulu organization said that the black paint, which members of the organization wear, is not blackface but is used as an alternative to masks, which Black Americans were prohibited from wearing.

The krewe briefly gave up the black face paint in order to garner new members but began painting their faces again once membership increased. James Russell, who served as president of the Zulu organization at this time, is credited with keeping the group together, easing tensions and welcoming in new members.

The Zulu Ensemble

In the early 1980s, the Zulu Ensemble was formed. The choir performs at local churches, funerals, school functions, the Jazz and Heritage Festival, and Celebration in the Oaks.

“The early ’80s is when Zulu became more than just a Mardi Gras krewe,” Hamilton said. “We started having more community involvement.”

Community involvement is the backbone of the Zulu organization, and the group participates in charitable events such as distributing food baskets and donating funds to schools and other organizations that help those in need. Zulu members also contribute to Toys for Tots and the Southern University Scholarship Fund.

The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club is proud to be open to men from all walks of life and of every race. Calling themselves an “everyman club,” Zulu has recruited men from various professions and races and prides itself on being the first parading organization that was racially integrated.

The coconut throw

At the Zulu parades, the most sought after catch is the “Zulu coconut.” Coconuts were first thrown in 1910, in their natural (unpainted) form. The painted and decorated treasure, which has been a crowd favorite and a “must” catch on Mardi Gras day, originated in the 1940s. The history of the coconut throw is simple- while other krewes were throwing glass beads, they were too expensive for the members of Zulu, so they decided to purchase inexpensive coconuts from the French Market.

“Zulu invented the signature Mardi Gras throw,” Hamilton said. “When you see other krewes throwing that one signature throw that everyone wants to catch- they got that idea from us!”

In 1987, due to lawsuits brought on by people injured by thrown coconuts, the krewe couldn’t renew its insurance coverage and was forced to put its coconut tradition on hold. However, in 1988, a “Coconut Bill” relieved the krewe of liability from injury, and the throw was, once again, a part of Carnival practice.

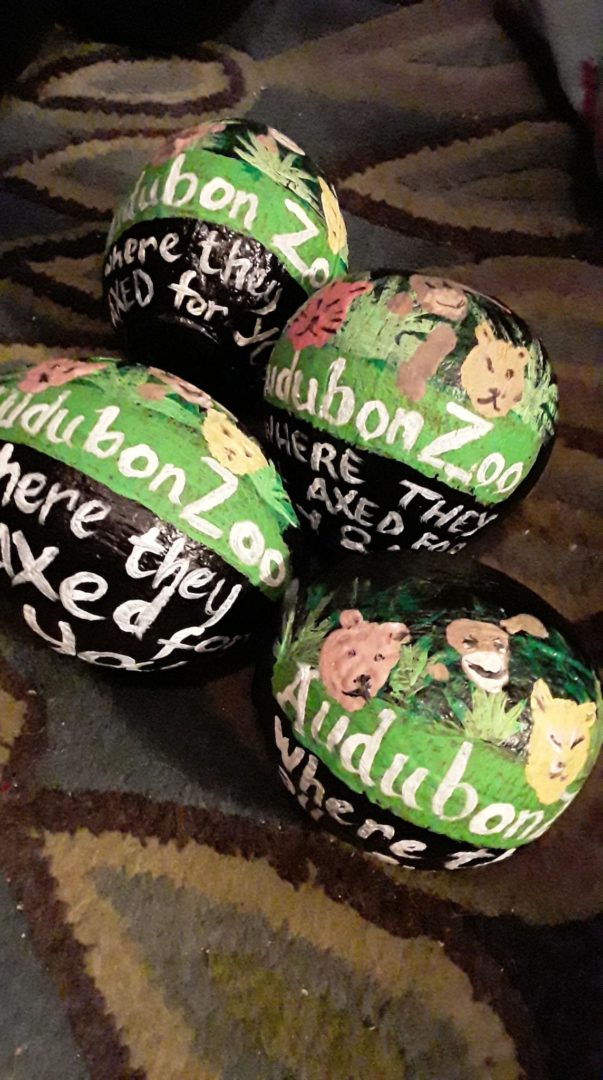

Custom Zulu coconuts

While many krewe members paint their own coconuts, some more artistic folks paint them for the krewe. Michelle Kavanaugh was hired to paint Zulu coconuts five years ago after she was asked to help by friends who ride in Zulu.

She begins the process in September and takes custom orders.

“The coconuts come cleaned and ready to decorate with a base coat of black, silver or gold paint,” Kavanaugh said. “Mostly I use paint, but I do use fake flowers, feathers, rhinestones, slick “puffy” paint, hot glue and beads. My customers prefer not to use glitter.”

The process for each coconut takes time and Kavanaugh likes adding her own special touches to her designs.

“A lot of the time I’ll have to use two coats of paint to get maximum coverage,” she said. “Since my coconuts are more elaborate than a plain ‘Z’, I try to think of things that are native to New Orleans, which takes some thought. I only do five of the same design.”

She continued, “After I have completed the design, I spray each one with a clear coat to protect them. Then I bag them individually in clear bags. I have tables set up all over my house and by the week before Mardi Gras my entire house is filled with coconuts!”

Sarah Barrow has been dubbed the “Coconut Lady” for her work on the Zulu coconuts. She’s been painting for 20 years and she paints about 7,000 coconuts a season. She has the honor of painting King Zulu’s coconuts.

“My favorite designs are the designs I do for the elected King Zulu each year,” Barrow said. “I’ve painted for over six King Zulus who all have a very detailed design. [The Zulu organization] has given me a way to fuel my passion for art. I’m a teacher by day, but being an artist is my passion.”

Zulu has had its share of difficult times. Membership slowed in the 80s and 90s and Councilman Roy E. Glapion, Jr., who served as Zulu president from 1976 to 1988, is credited with encouraging more professionals to join the krewe. He’s also responsible for holding the krewe to a higher standard and insisting on better float quality and consistency.

Carnival after Katrina

Carnival after Katrina was particularly trying.

“Membership dwindled after Katrina because krewe members were scattered all over the country,” Hamilton explained. “A lot of our people lost everything. I was Zulu president then, and I knew that we had to roll in 2006, even with the limited members we had at the time. I knew that the other krewes were going to be looking to us to see what we were going to do.”

In December 2020 , The Zulu Social Aid and Pleasure Club announced that the organization would not name royalty and other dignitaries in 2021. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, the City of New Orleans canceled all Mardi Gras parades, and the Zulu parade will not roll for the 2021 Carnival season.

Zulu President Elroy James issued a statement explaining that the election of club dignitaries had been postponed, and then altogether canceled, due to the outbreak. James said that it is also likely that the Zulu ball will be scaled down, or canceled completely.

In the past, the parade and ball were canceled due to krewe hiatuses, World War II, and the 1979 police strike.

Coronavirus has dealt a personal blow to The Zulu Organization, as well. Several members have died of the disease, including Cornell Charles, a coach and mentor to children, and 2007 Zulu king Dr. Larry Hammond.

New Orleans Mayor LaToya Cantrell referred to Hammond as a “culture bearer in the truest sense,” on Twitter .

It breaks my heart to mark the passing of Dr. Larry Hammond, Zulu King in 2007. A vital part of our City’s rebirth after Katrina, & a culture bearer in the truest sense. We mourn his passing & all COVID victims, with a heavy heart. May he rest in peace. 📸: @asolidphotography pic.twitter.com/UQIeJPdZvI

— Mayor LaToya Cantrell (@mayorcantrell) April 1, 2020

Several other members were hospitalized, or forced to self-quarantine, due to the disease.

Since there will be no ride, Kavanaugh and Barrow won’t be painting their beloved coconuts this year, but they look forward to painting again for the 2022 Mardi Gras season and spreading the joy of Zulu.

Kavanaugh says that the importance of the Zulu organization can’t be overstated.

“Other than being a fantastic Mardi Gras club, the philanthropic efforts by the club often go unacknowledged,” she said. “It’s very nice to know an organization like this is constantly giving back to the community.”