A photo of a kitchen that looks somehow full and desolate at the same time.

An email from Jefferson Parish Schools Superintendent Cade Brumley.

A snapshot of a hand-washing station at Faubourg Wines.

It’s a weird collection of thoughts, notes, photos, correspondence and signage, but these are the things that may, one day, help piece together the real, lived experience of the coronavirus in New Orleans and throughout the world. Part of The Journal of the Plague Year, this project is meant to chronicle and curate what comes of this unique and strange moment in history as the world grapples with a new reality shaped by the coronavirus. Spurred on by the value they saw in a similar project after Hurricane Katrina, researchers at the University of New Orleans’ Midlo Center for New Orleans Studies are spearheading local collection of these artifacts.

“On March 15, I got a note that something had been canceled,” recalled Midlo Center co-director Dr. Connie Zeanah Atkinson. “I immediately saved it.”

Atkinson quickly learned of The Journal of the Plague Year, which despite having started at Arizona State University, is modeled in part after UNO’s endeavor in New Orleans when artifacts and mementos of Hurricane Katrina were gathered in a similar way.

That collection, the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank, comprises more than 25,000 contributions.

“Texts from moms looking for their children, or pictures of signs of homes or children’s contributions were particularly heartrending,” Atkinson said of the Hurricane Digital Memory Bank. “But those things can, at the moment, be lost after awhile. You’ve forgotten those strategies you use to survive, things that worked, things that didn’t work. We lose that, and if we can collect them, it might help.”

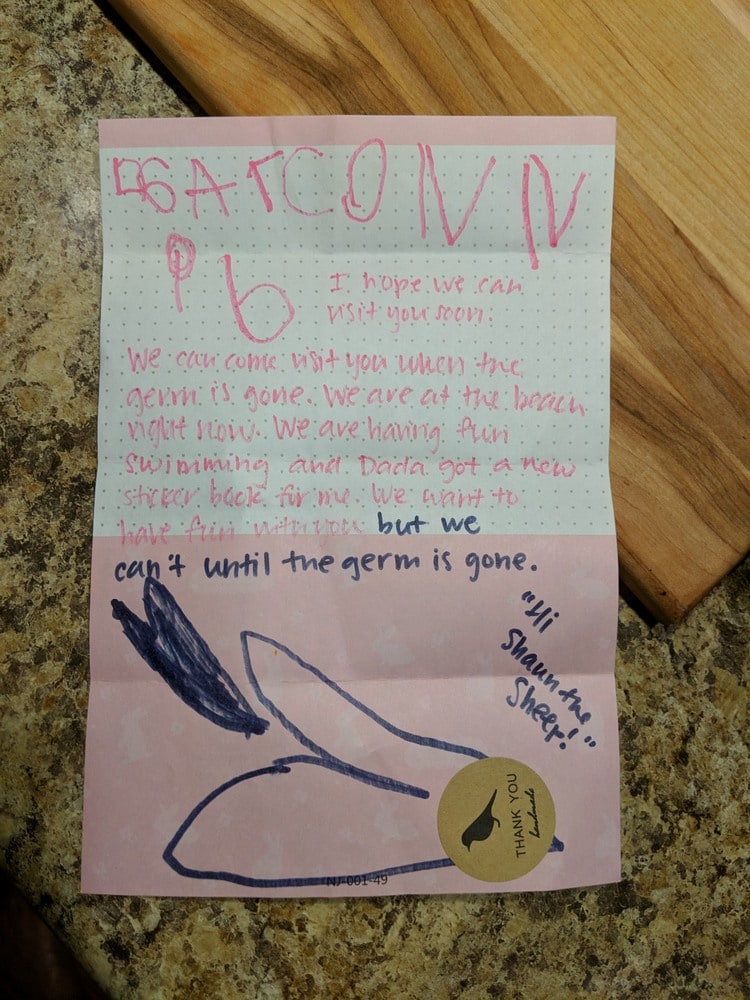

Credit: Hattie Jane Parker, “A Letter from 4-year-old Hattie to her Great Aunt, New Orleans, LA,” A Journal of the Plague Year: an Archive of CoVid19, accessed May 4, 2020, https://covid19.omeka.net/items/show/2564

Much has changed since the Katrina project, including the digital capability to gather these mementos, and the coping mechanisms to face an unprecedented disaster.

“We were thinking this would give us another great opportunity to have people in the arts, music and hospitality industries tell us what’s going on in their lives right this second,” said Atkinson, who before her turn as a researcher was a music journalist here in New Orleans. “People are coming up with strategies, these virtual concerts, and these will help us in the future, but also it might help these hospitality and cultural people get some help during this disaster.”

Contributions to the Journal of the Plague Year span the globe and take shape in a myriad of ways, but they all shed light on the intricacies of a daily life that has changed so drastically since the coronavirus first appeared.

The New Orleans contributions highlight the specific ways of life here: A calendar of a musician’s gigs, all canceled; a closed sign on the front of Snug Harbor, a snapshot of a vanity license plate that just reads “UGH WHY.”

“Evocative things of the moment, that’s what we want,” Atkinson said. “We want personal things.”

Anyone can contribute to the Journal using its online portal, but some submissions require manual entry. That’s where New Orleans Historical managing editor Kathryn Anne O’Dwyer comes in.

Credit: Rick Olivier, ““Ugh Why” Automobile Vanity License Plate, New Orleans, LA

,” A Journal of the Plague Year: an Archive of CoVid19, accessed May 4, 2020, https://covid19.omeka.net/items/show/1363.

“Sometimes, it is really heavy stuff, memorials for people passing away, people sharing different ways they’re attempting to mourn family members and friends, and while it’s really sad to think about this person passing, people are using the archive to show the world how they are getting through it, and it is actually really uplifting,” O’Dwyer said. “There’s a lot of public art — sidewalk chalk — memorializing people. It brings a cheerfulness to this really horrible thing that’s happened.”

So far, there are about 175 contributions from New Orleans among about 2,500 total worldwide, each of which represents a bit of sober grounding for the often dizzying experience of a pandemic. (Submit yours here.)

“You can curl up in the fetal position and be fearful, or you can watch reruns all day, and it doesn’t work. It doesn’t fill up the time, and it doesn’t help,” Atkinson said. “… Just being able to put down your digital contribution of how you feel and send it out into the world, it’s a little bit of a pushback against the virus.”