A speakeasy recently opened up below Orpheum Theater — a callback to the 1920s, when shady characters with memorable nicknames illegally provided Prohibition-weary New Orleanians with the booze they so badly wanted.

Of course, this underground bar — called Double Dealer — is attracting patrons of the more upstanding variety. This guy, for example:

View this post on Instagram

Speakeasies from a century ago, on the other hand, sometimes attracted a more notorious crowd. One whose name started with an “M”…and ended with an “afia.”

You look over your shoulder.

“But, c’mon, Matt,” you whisper, because you don’t want a Made Man to overhear you, “the Mafia wasn’t happening in New Orleans, was it? It was a New York and Chicago thing, right?”

Wrong.

Not only was New Orleans a center of America’s network of Mafia families… many historians believe New Orleans was the original center.

Can I trust you? Let me tell you a story.

From Sicily to New Orleans

Italy wasn’t a unified nation until 1861. Earlier that century the Mediterranean island of Sicily was merged into a kingdom with Naples, though Sicilians wanted their independence. That dream was briefly achieved in 1848 when they revolted and won, but Naples took back control the next year and enacted oppressive policies toward the rebel island. Those policies — combined with a local economy that struggled to compete in a unified Italy — triggered a diaspora of Sicilians across the Atlantic Ocean that lasted more than a half-century.

No city in America received more Sicilians from that exodus than New Orleans. Between 1884 and 1924 an estimated 290,000 Italian immigrants — many from Sicily — arrived here.

MORE: Stories of the New Orleans Mafia as told by mob associate Frenchy Brouillette

But why choose New Orleans?

The winding down of the American Civil War allowed freed former slaves the choice between staying in rural areas to work the fields, or heading to cities for higher-paying jobs. Not surprisingly, many chose to leave.

The Louisiana Bureau of Immigration was formed to recruit new agricultural workers, but it also had success attracting Sicilians — offering them the opportunity to move beyond their previous lives of subsistence farming.

Raffaele Agnello arrived in New Orleans earlier than most — by about 1860. He was a Sicilian from Palermo (located in western Sicily) and was already a mafioso before leaving his homeland. When Confederate forces and local police abandoned New Orleans during the Civil War, Agnello was a leader in the European Brigade — a group of immigrants tasked by the mayor to keep order in the city. His position in the brigade helped him consolidate local Italian power into NOLA’s first Mafia, earning him the nickname Zu (or Uncle).

Agnello and his brother, Joseph “Peppino,” gained strength as more Sicilians from Palermo flooded the city. They controlled the Italian dockworkers and skimmed money from the fruit trade those workers handled.

This attracted the attention of Joseph “J.P.” Macheca, a man born and raised in the Italian-American community of New Orleans and heavily involved in the importing of fruit.

Macheca organized and funded The Innocenti, a politically motivated group that gained support from New Orleanians with ties to the eastern side of Sicily. The Innocenti set up guards and patrols around the French Quarter — called Little Palermo — and that felt like a threat to Agnello, triggering America’s first Mafia War.

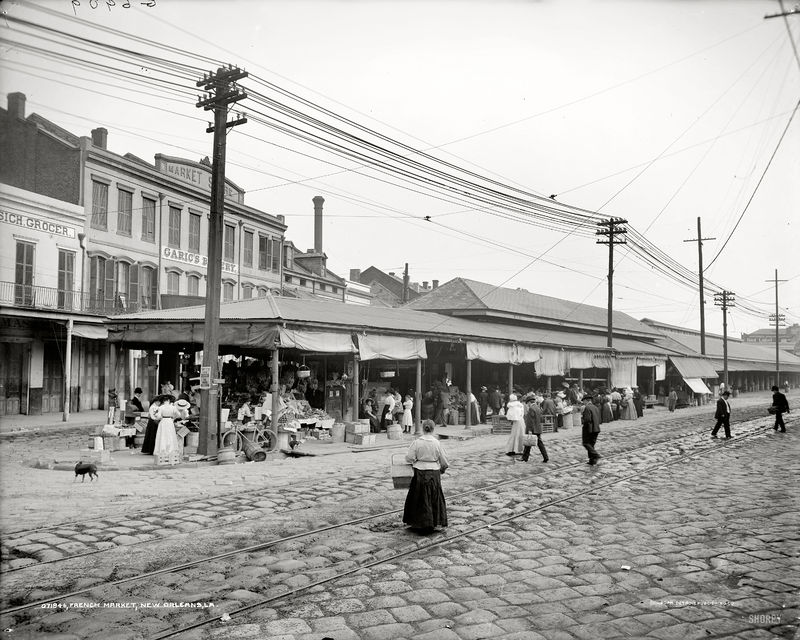

It was a bloody and complicated affair, involving political officials, set-ups and a whole lot of “whacks,” but we don’t have time for all that here. Suffice it to say that on the morning of April 1, 1869, Raffaele Agnello, the first Godfather of New Orleans, walked by the French Market and through the Quarter with his bodyguard, greeting his supporters. The two turned the corner from Old Levee Street (now Decatur Street) onto Toulouse Street, just outside the J. Macheca & Company fruit store. The bodyguard was distracted from a sound behind them, and in that instant Agnello was shot in the face and killed.

His brother, Joseph, was killed a few years later, leaving New Orleans’ organized crime network to Macheca.

The Black Hand

Macheca and his group fell under a Mafia splinter group based in Monreale, Sicily, called the Stuppagghieri. Beginning in the 1870s, they established lucrative organized criminal activities such as extortion (with noncompliant businesses set aflame), labor racketeering and — like their Agnello-led predecessors — collecting tribute payments from Italian laborers and dockworkers. They also collected payments from the powerful, rival Provenzano crime family… at least for a while.

By the early 1880s, Joe Provenzano was dominating operations on the docks, and decided to split from Macheca’s Stuppagghieri. For the next six years, the two sides imported hundreds of Sicilian criminals to bolster their strength — with the Provenzano group pulling from the Palermo Mafia that once supported AgNello, and Macheca being supported by the Stuppagghieri. War broke out again in 1888.

For decades the city’s nonItalian residents were growing increasingly angry with their new neighbors. As far back as 1869, the New Orleans Times wrote how parts of the city were overrun with “well-known and notorious Sicilian murderers, counterfeiters, and burglars, who — in the last month — have formed a sort of general co-partnership or stock company for the plunder and disturbance of the city.”

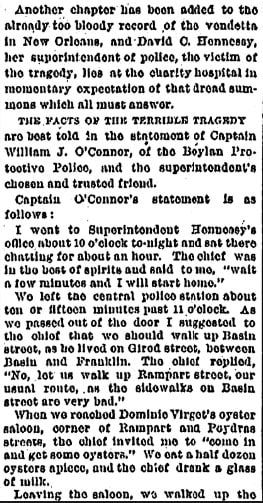

Cleaning up the streets was tasked to David Hennessy — 29 years old and just recently appointed to be New Orleans’ police chief. Hennessy had a history of fighting organized crime, capturing the notorious Giuseppe “Vincenzo Rebello” Esposito, wanted in Italy for — among other things — kidnapping a British tourist and cutting off his ear.

Hennessy made progress mediating the war between the two factions, but — on the night of Oct. 15, 1890 — he was shot by several sawed-off-shotgun-wielding gunmen on his way home beside where Borgne is today. He died the next day, but was said to have blamed the “Dagos” — a derogatory term for Italians. (In the article excerpt, below, written hours after the shooting, I love how it was noted that the fallen chief’s last meal was a half-dozen oysters and “a glass of milk.” Only Hennessy and only in New Orleans.)

Hysteria swept over the city and as many as 250 Italians were rounded up for questioning. Nineteen men were ultimately charged with the murder — or as accessories — and held without bail in the parish prison just upriver of where the Mahalia Jackson Theater now stands. One of those men was Joseph Macheca, and — when none of the men were found guilty — an angry mob of thousands of New Orleanians stormed the prison. Eleven of the 19 were lynched or shot, while the others were able to hide.

Many believe this to be the largest single mass lynching in U.S. history.

A Modern Mafia

Macheca was among those lynched, but one of his top lieutenants, Charles “Millionaire Charlie” Matranga escaped and became the crime family’s new leader. He pushed the rival Provenzanos out to Florida and profited from rackets including operations on the docks, prostitution, narcotics trafficking, gambling and — starting in 1920 with the advent of Prohibition — bootlegging.

Matranga retired in 1922, turning over leadership to Sylvestro “Silver Dollar Sam” Carolla. Carolla forced out rival bootlegging gangs over the remainder of the decade, eventually gaining full control of the increasingly profitable racket.

He used this clout to gain political connections — evidenced in 1929 when Al Capone came to town. New Orleans was called “the liquor capital of America” and Carolla supplied Mafia families around the country with booze during Prohibition. Capone arrived at New Orleans Union Station to demand Silver Dollar supply him rather than a rival Chicago family. Carolla met Capone and had several police officers he controlled break the thumbs of Capone’s bodyguards, flexing the muscle of our local Mafia.

In the 1930s, trouble in New York meant opportunity in New Orleans. New York Mayor, Fiorello La Guardia, attacked the slot machine business of New York mobsters such as the “Prime Minister of the Mob” Frank Costello, and Phillip “Dandy Phil” Kastel. Carolla negotiated a deal with the mobsters — as well as with then-Louisiana Sen. Huey Long — to bring slot machines to Louisiana instead. He placed the operation under his lieutenant, Carlos “Little Man” Marcello, who ran profitable illegal gambling operations undisturbed for years.

The Little Man

When Carolla got into legal trouble resulting in his deportation, Marcello began his reign as the most powerful Mafia boss in New Orleans history. The “Little Man” — named as such because he was only 5foot, 6 inches tall — teamed with nationally famous organized crime figure Meyer “Mob’s Accountant” Lansky to split profits from the most important casinos in the area. He also provided muscle in Florida real estate deals in exchange for a cut of money skimmed from select Las Vegas casinos.

(Marcello also earned his early money by forcing local businesses to carry pinball machines and skimming from their profits. Makes you wonder where Kebab got all those machines, hmmmm.)

View this post on Instagram

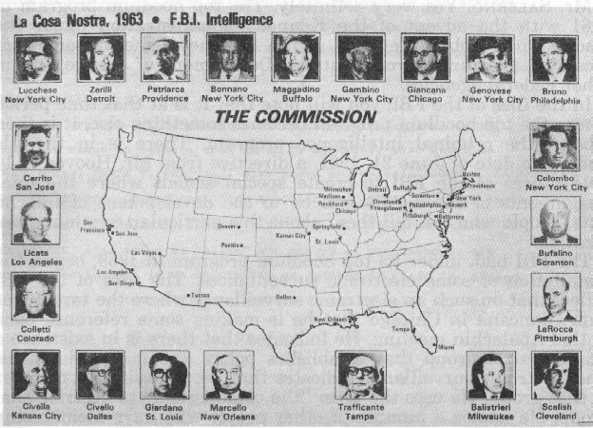

Whereas many of New Orleans’ early Italian mob leaders faced their biggest challenges from other mob families, Marcello faced his from the federal government. As the first half of the 20th century wound down, “Lucky” Luciano organized the United States’ major crime families into a national network. This took place as major newspapers and magazines — as well as local “crime commissions” in major cities — uncovered extensive corruption of the political process by organized crime.

In 1951, the U.S. Senate’s Kefauver Committee, formally and extensively investigated the role of organized crime in the country. Marcello appeared before the committee on Jan. 25, where he famously pleaded the Fifth Amendment 152 times. The senators called Marcello “one of the worst criminals in the country.”

The McClellan Committee investigated organized crime once again in 1959. Sen. John F. Kennedy was a member of the committee and his brother, Bobby, was its chief counsel. Marcello once again refused to answer questions, setting off a vicious feud between himself and the Kennedys.

MORE: In 1890, A New Orleans Police Chief Was Gunned Down By The Mafia

A few years later, as Attorney General in his brother’s Administration, Bobby had Marcello deported to Guatemala. (Like — Kennedy basically kidnapped Marcello and literally dropped him in the middle of the Guatemalan jungle. That’s ice cold by Kennedy and deserves a story of its own!) Little Man was almost killed there, but fought his way back to the United States. Two years later, Bobby had him tried for multiple charges of conspiracy, but Little Man was able to outmaneuver his nemesis once again.

Not to dive too far down the conspiracy rabbithole, but many believe the assassination of President Kennedy was the doing of Marcello, pointing to his connections to, both, Lee Harvey Oswald (Oswald’s uncle was a Lieutenant for Marcello) and Jack Ruby (who owned a strip club in Dallas that worked closely with one of Marcello’s). The House Select Committee on Assassinations reported, “The committee found that Marcello had the motive, means and opportunity to have President John F. Kennedy assassinated, thought it was unable to establish direct evidence of Marcello’s complicity.

Marcello was famous for telling people during this time that “If you cut off a dog’s tail it will continue to bite you, but if you cut off the dog’s head it will cease to cause you trouble.” In the decades that followed, several witnesses provided additional evidence to believe Marcello cut off the head, and — when he did — Bobby Kennedy was out of power.

The Mafia Today?

For 30 years, Marcello successfully ran the New Orleans Mafia, often hosting meetings at Mosca’s in nearby Avondale, a delicious old-school Italian restaurant inside a building he happened to own. (Marcello’s son still owns the building.)

View this post on Instagram

In 1982, Marcello was convicted of several crimes involving corruption, labor racketeering, bribing a federal judge and the accepting of kickbacks in exchange for large state insurance contracts. He was in jail until 1989, when he suffered a series of strokes. He announced his retirement and died on March 2, 1993, in his Metairie home.

The deathblow to the New Orleans Mafia appeared to be dealt in 1995 and 1996, when the new boss, Anthony Carolla (son of “Silver Dollar”), as well as underboss, Francis “Muffaletta Frank” Gagliano, were sentenced to several years in prison for attempting to skim from the burgeoning video poker industry. Gagliano’s son, Joseph, was given 2 ½ years for a scheme to defraud the President Casino in Biloxi by marking blackjack cards with invisible ink.

How’d the FBI discover these plans?

Easy. They wiretapped Frank’s Deli (named after “Muffaletta Frank” and known today as Frank’s Restaurant) in the French Quarter beginning in 1993. The sting was known as “Operation Hardcrust” — supposedly because of the stale bread undercover agents were forced to eat while at Frank’s. (Ouch.)

View this post on Instagram

The public didn’t hear much from the city’s Mafia after that. Then, on May 7, 2015, two Metairie men were pulled over in response to a tip. When the police checked the vehicle, they found it was a stolen van outfitted with makeshift gun ports, a sniper rifle with a silencer, and 80 feet of cannon fuse. The driver was Dominick Gullo, known for staging poker tournaments around the country, and the passenger was Joseph Gagliano — the previously incarcerated son of former underboss, “Muffaletta Frank.”

The two men claimed they had just purchased the van a few hours prior and were not aware of what was in the back. Later, they said they had outfitted the van to sell snoballs.

I’m no detective. It’s totally possible they were about to sell snoballs out of the back of a van with a sniper rifle and cannon fuse.

Or…maybe… just maybe… they were up to something else.

View this post on Instagram

Additional Resources:

Brouillette, Frenchy. Mr. New Orleans: The Life of a Big Easy Underworld Legend, Phoenix Books, 2009.

Kelly, Robert J. Encyclopedia of Organized Crime in the United States. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2000.

Kurtz, Michael L. (Autumn 1983). “Organized Crime in Louisiana History: Myth and Reality”. Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 24 (4)

The Brackish Podcast. “Episode 6: Carlos Marcello.”Apple Podcasts. September 13, 2019.

MATT “THE WRITER” HAINES LIVES IN NEW ORLEANS. HE’S NOT A MADE MAN, BUT PLEASE FOLLOW HIM ANYWAY AT MATTHAINESWRITES.COM, AND ON FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM AND TWITTER.