The neighborhood of Oakland is known for its historic spots – the Carnegie Museum, the main branch of the Carnegie Library and the towering Cathedral of Learning, to name a few. Since this summer of social distancing is turning into the semester of social distancing, we’ve put together a self-guided tour of some of the other historic spots in Oakland that should be on your radar. While the neighborhood has many historic buildings, here is a look at some of the history and art you can find outside.

WESTINGHOUSE MEMORIAL

The pleasures of Schenley Park are well-known, well-used, well-loved, from the nature trails on which to walk and run to rolling hills on which to picnic to the fields through which to throw a frisbee back and forth. It’s generally bustling and boisterous, even in times of directed quarantine and confinement, and is a lot of fun. But sometimes you’re looking for something different, repose instead of exuberance, meditation rather than motion. For a gentle place suitable for looking inward, head out to Westinghouse Memorial.

This monument to George Westinghouse, an entrepreneur in railroads and electricity, a rival of Thomas Edison, a supporter of Nicola Tesla, was initially funded in 1930 by small donations from over 55,000 employees. A decade or so ago, it began to show some metaphorical cracks around the edges and has recently been fully restored to a state of subtle glory. A pond with lush water lilies fronts bronze sculpture and relief depicting the story of Westinghouse’s rise, bounded by graceful trees and welcoming benches. You will likely see ducks and possibly a turtle.

It’s unquestionably lovely, a serene, quiet space, tucked away, not quite secret, but private and intimate in feeling, distinct from the activity of the park.

CMU CAMPUS

Even in the summer, there’s typically a populace moving and shaking on CMU’s grounds, artists and actors and scientists and scholars putting in the work to do their part to improve the world with the contribution their talents best can make. Right now, however, it’s a bit of a ghost town, the campus desolate and empty.

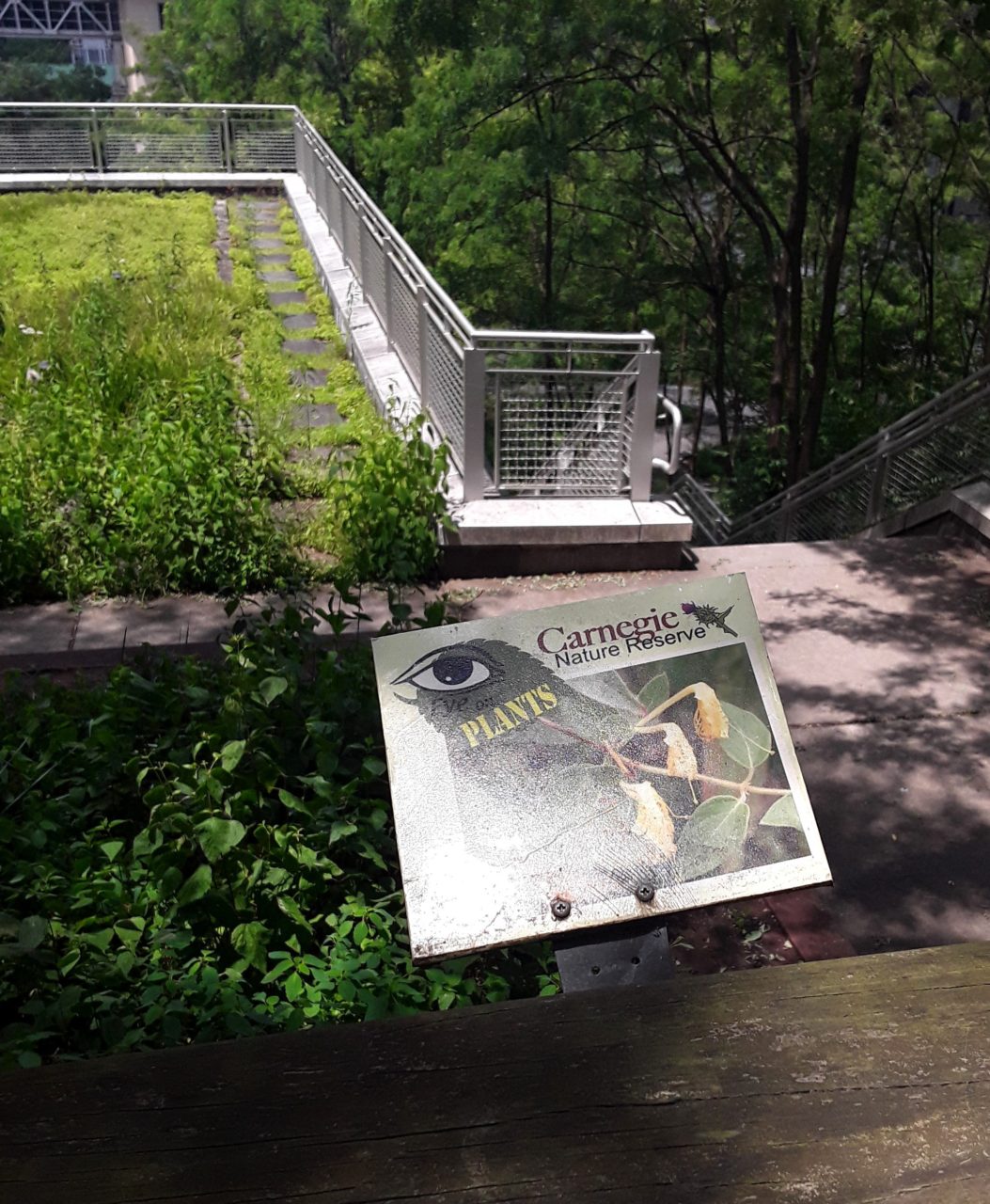

Of people, anyway. But while the student body, and bodies, are elsewhere, the space remains, the spaces within it solitary and ripe for exploration. Works of art, nature, and humanity are worthy of our active observation or can provide a place for us to be peacefully idle. Arresting sculptures command our attention while delicate hidey holes whisper and draw us in. There are platforms nestled off the beaten path to observe wildlife now jungle-like as left all to itself, as well as manicured lawns which bear the signs of humankind awakening to others. It’s a place that offers much to learn even to those who aren’t enrolled.

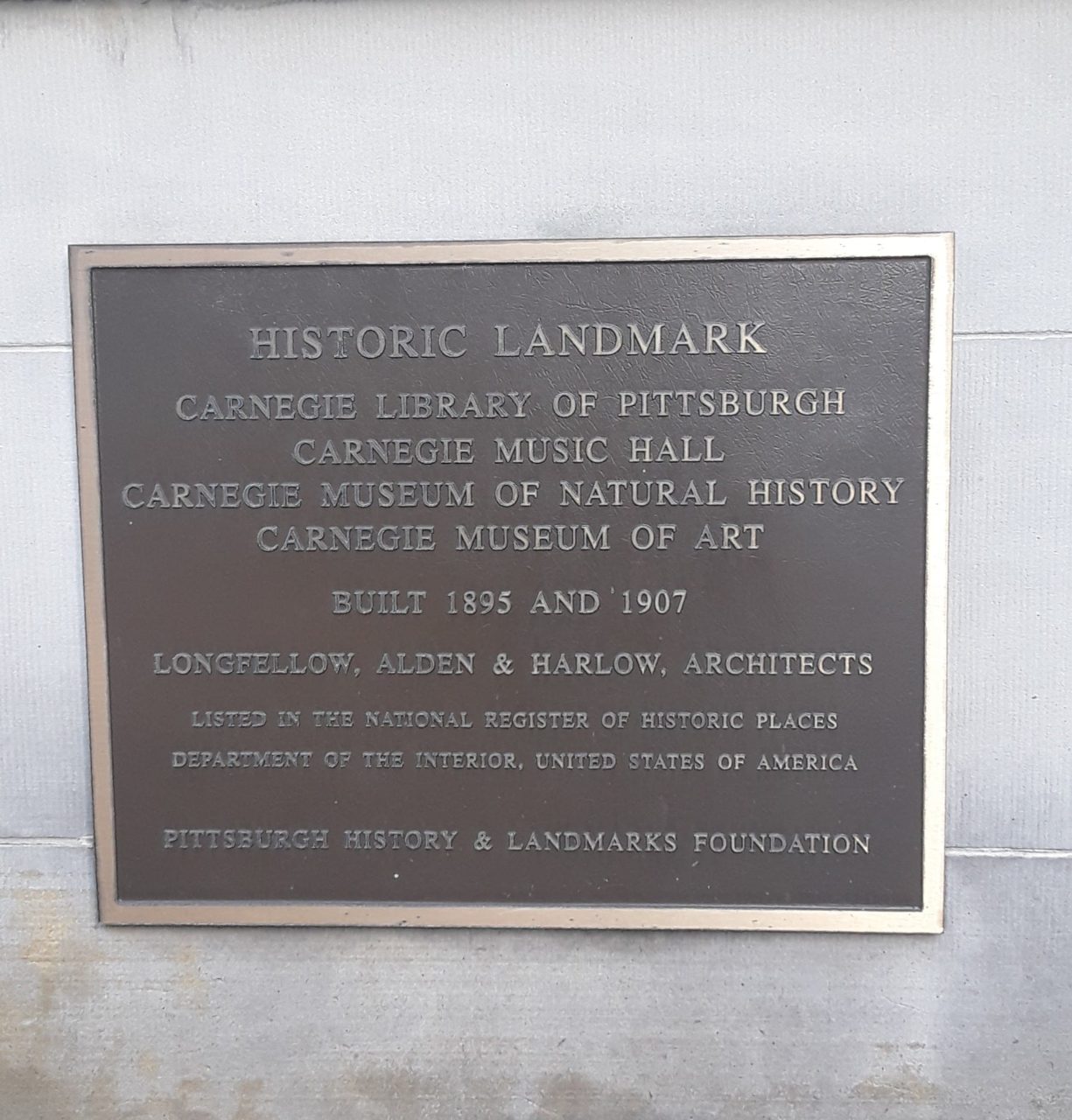

THE CARNEGIE INSTITUTE

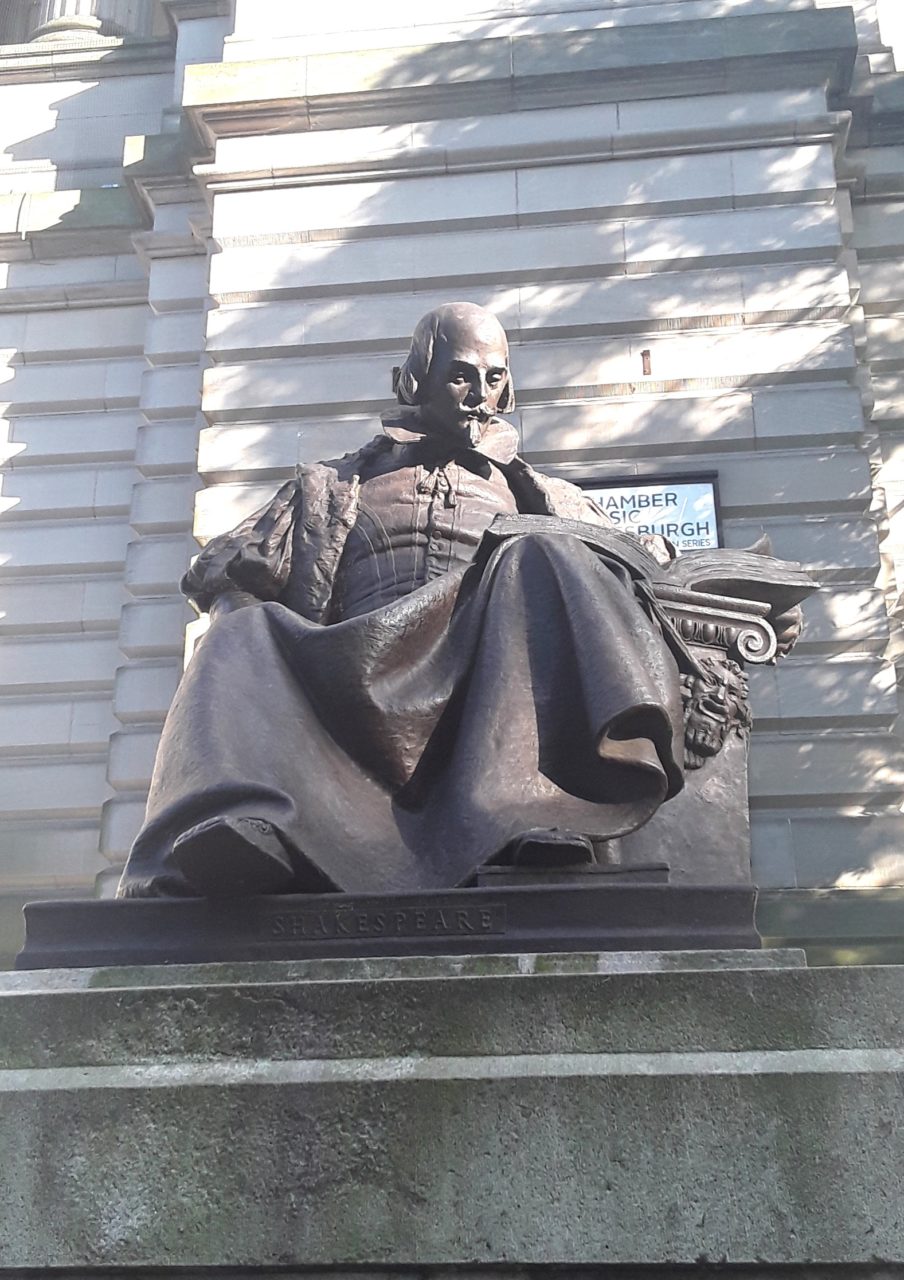

We may refer to it as the Carnegie, the library, the museum (though there’s more than one contained within), but the structure itself is the Carnegie Institute. Stretching from Schenley Plaza to Craig Street, this Beaux-Arts classical formation was intended to be a tribute to human knowledge and investigation, uniting the arts and sciences. It was a gift to the city bearing the name of the giver, demonstrating his generosity and altruism, even if those whose labor underwrote its construction worked too many hours to ever have time to visit.

It’s a properly flamboyant and suitably grand demonstration of the largesse of an industrialist benefactor, with a multitude of features worthy of close inspection. More obvious eyecatchers are the list of names of men of great accomplishments (yes, unsurprisingly, men) scrolling around the building and the sculptures of men of great accomplishments (yes, men) that flank the doorways. But there’s also tiny, less commanding details deserving of attention- ornate carving in stone, subtle casting in metal, the precision of the lighting elements. Patience in examining what’s smaller here brings rewards.

OUTDOOR SCULPTURES AT CMOA

When we think about observing the works on display at the Carnegie Museum of Art, we might imagine summiting broad flat steps to reach a warren of connected galleries, hushed and curated, through which we stroll to take in carefully lit paintings, sculpture, furnishings under the watchful gaze of a jacketed guard. While this is certainly a common shared element of a museum visit, it’s not the only way to experience the collection; in fact, it’s not even necessary to pass through the doors to get a glimpse of what’s on view.

The building is surrounded by sculpture, both at the main entrance at Forbes and Craig and past the parking lot in the courtyard behind. The latter area includes George Rickey’s kinetic work “Two Slender Lines” which shifts and sways with the wind, “Night” by Ariste Maillol seeking rest and solace upon and within itself, Jack Youngerman’s examination and interpretation of a masterwork with “Hokasai’s Wave.” Inside, but clearly visible, is a 1991 untitled Christopher Wool piece.

In front, Richard Serra’s “Carnegie” hulks and looms over the pavement, while Henry Moore’s “Reclining Figure” demonstrates gentle repose. Of course, what can be seen streetside is a mere fraction of what the museum holds, but this handful of pieces is enough to be worth perusal.

DIPPY

On July 4, 1899, William Harlow Reed found a toe bone near Medicine Creek, Wyoming. The toe bone connected to the foot bone, the foot bone connected to the ankle bone, and so on and so forth until all the connected bones revealed the skeleton of a dinosaur, specifically the Diplodocus. Reed was funded by Andrew Carnegie on this expedition, so the bankroller’s museum became the home of the single most famous dinosaur skeleton in the world, the first that millions had ever seen. Its likeness has been reproduced in museums around the planet with donations of plaster casts, but the original lives here. We call him Dippy.

In 1999, a statue was created from the original fossil to commemorate the 100 year anniversary of his discovery. Standing at the corner of Forbes Avenue and Schenley Plaza, at the adjunct of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History and the main branch of the Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh, he’s a symbol of the museum and a replica of a dinosaur, but he’s also a member of the community, and a reflection of it. He bundles up for inclement weather, sports the colors of professional and collegiate sports teams, wore black to join our mourning when the city was rocked by the Tree of Life shooting.

Right now, he’s wearing a mask.

LOCATION OF STEPHEN FOSTER STATUE

Next to Dippy, up against the intersection, is an arrangement that’s a little curious. A quartet of flowerbeds bursting with color flank a rounded middle, center, central, the landscaping is directing your attention to lean into this circle as its focal point. Everything guides you there, so you look. But there’s nothing to see.

For over a century, there was. Giuseppe Moretti designed the public sculpture Stephen Foster to honor the eponymous composer, the Pittsburgh-born songwriter responsible for “Beautiful Dreamer,” “Camptown Races,” “My Old Kentucky Home.” Foster wrote a lot of songs about the South, though never lived there, and his works were frequently performed by blackface minstrel groups. As opposed to the mockery that characterized most minstrel songs of the period, Foster’s works looked at slavery and Black people with sentimentality.

One of these was “Old Uncle Ned,” a song mourning a departed field slave. Moretti opted to include the figure of Ned in his artistic tribute, a heavy-browed, grinning banjo player. When the statue was erected in 1900, everyone thought it was just fine. For the last few decades, though, looking at it through a sharper lens revealed it to many as problematic. Active work against its removal began in earnest in 2000; this intensified following protests in Charlottesville, Virginia, in 2017 against that city’s confederate monuments. On April 26, 2018, it was finally removed.

The intention has been to erect in its stead a work paying homage to an African American woman prominent in Pittsburgh’s history. As of now, the space is empty.

FORBES FIELD

On June 30, 1909, the Pittsburgh Pirates hosted the Chicago Cubs in the first game at what was then one of the grandest parks in baseball, The Oakland Orchard, AKA the Old Lady Of Schenley Park, AKA The House of Thrills, AKA Forbes Field.

The Pirates lost.

Over the next six decades, the park was the territory of not only the Pirates, but additionally the Homestead Grays until they disbanded in 1951. It was home to players Honus Wagner, Pie Traynor, Cool Papa Bell, Josh Gibson, Willie Stargell, Bill Mazeroski, Dock Ellis, and the greatest man who ever lived, Roberto Clemente. There the Pirates won three World Series, the first live radio of an MLB game was broadcast, the last tripleheader in MLB history was played, and football and boxing took place as well.

While we have bragging rights to the most gorgeous park in the game with PNC, visiting baseball aficionados still make a point to check out where Forbes Field used to be, the wall that remains, standing as strong as our love of the game.

On June 28, 1970, the second game of a doubleheader against the Cubs, Bill Mazeroski recorded the final out at Forbes Field.

The Pirates won.

More tall tales and fun facts about the Oakland neighborhood

- Say hello to @VintagePitt, an entire Instagram account of Pitt history.

- Before it was home to the Allegheny County Health Department, this building was the Croatian Fraternal Union; we take a look at the significance of this building’s architecture.

- A not so brief history of The Original Hot Dog Shop, an Oakland landmark for decades, which closed in 2020.

- Hidden houses. We talk to historian and archivist Charles Succop about some of the houses that are hidden behind a neighborhood.

- Buried bridges. Take a listen to our interview with historian Justin Greenawalt and learn more about a buried bridge and the history of the Pittsburgh potty.

Looking for more walking tours?

- Check out our self-guided walking tour of Downtown.

- Artist Laura Zurowski has been climbing and photographing all of the steps in Pittsburgh, and she offers tours of city steps with the folks at Threadbare. (Check out our interview with Laura about her quest to climb all of the steps.)