As the first widely publicized Black Civil War hero, Captain André Cailloux of the United States Army 1st Louisiana Native Guards became an enduring symbol of equality and suffrage.

Cailloux lived when New Orleans had three categories of laws for the enslaved, free people of African descent, and whites. Cailloux was born enslaved in 1825 near Pointe a la Hache and was freed by his enslaver in New Orleans in 1846. Working as a cigar-maker and later opening his own shop in the Faubourg Marigny, he became a respected member of the free people of color community, but he and his community did not have the right to vote. He interacted with Afro-Creole mutual aid societies, who would become his brothers in arms in the Civil War. He and fellow Black soldiers joined the Union Army in defense of freedom for all and to bring an end to slavery.

The first Black regiment ordered into battle

Black novelist and historian William Wells Brown wrote of his contemporary, “[Cailloux] prided himself on being the blackest man in the Crescent City. . . educated, polished in his manners, a splendid horseman, a good boxer, bold, athletic, and daring, he never lacked admirers. His men were ready at any time to follow him to the cannon’s mouth; and he was ready to lead them.”

At double quick-time down Telegraph Road, Captain André Cailloux led Company E of the 1st Louisiana Native Guard toward the earthen battlements of the Confederate forces at Port Hudson, Louisiana, by the Mississippi River on May 27, 1863. Though Black soldiers participated in every major U.S. conflict beginning with the Revolutionary War, the Louisiana Native Guards were the first U.S. Army Infantry Regiment of African-Americans to be ordered into a battle.

“Louder than the thunder of Heaven was the artillery, rending the air, shaking the earth itself; cannons, mortars, and musketry alike opened a fiery storm upon the advancing regiments; an iron shower of grape and round shot, shells and rockets, with a perfect tempest of rifle bullets fell upon them. On they went and down, scores falling on right and left,” wrote poet historian Joseph T. Wilson, a Louisiana Native Guard veteran.

Capt. Cailloux shouted orders to his men in English and French as he led a charge alongside the 1,080 troops of the 1st and 3rd Louisiana Native Guards. The two regiments were comprised of free men of color and men who recently escaped enslavement. As soldiers fell from bullets and cannon fire in the swampy battlefield, Cailloux’s left arm was seen dangling by his side, broken by a gunshot. Cailloux refused to leave the battlefield and held his sword in his good arm shouting “En avant, mes enfants!” (Forward, my children!) and “Follow Me!” After multiple charges, Cailloux was mortally wounded by cannon fire.

Striving for equality in the heat of battle

All the charges by white and Black Union units failed, but the courage of the Black soldiers had impressed the commanding Union Major General Nathaniel Banks. The origin of “courage” is the French word “coeur” meaning “heart.” Poets, politicians, and historians wrote of how Cailloux and his men gave their hearts in pursuit of equality while facing the violence and death in the battle. They commended Cailloux, whose name can be translated from French as “the Rock,” for being unwavering in his duty. General Banks’ report praising the heroic and courageous sacrifice of the Louisiana Native Guards was published in The New York Times on June 11, 1863.

After the charges at Port Hudson, a truce was declared to bury the dead and the Union and Confederates recovered many white soldiers. However, the truce pact did not apply to the Black soldiers on Telegraph Road.

Walter S. Turner, a Confederate soldier, gave an account in his diary on May 28, 1863, that said the Union refused to recover the Black soldiers leaving them to “lie and melt in their own blood and to be made the prey of both birds and beasts.” Two months later, after the battle had ended, the Times reported that Cailloux’s body “lay within deadly reach of the rebel sharpshooters, and all attempts to recover the body were met with a shower of Minie bullets.” In the end, the Black soldiers were left to rot for more than a month, and Union General Banks made no coordinated effort to recover them.

When a second assault failed on June 13th, General Banks resorted to siege tactics by bombarding the Confederates with artillery and cutting off supplies. The rebels sought refuge in “rat holes” dug inside their earthworks to protect them from constant shelling. Low on supplies rebels resorted to eating rats while others deserted or died from disease.

Death at Port Hudson A super-spreader of disease

More than 5,000 soldiers died from disease on both sides at Port Hudson. In some respects, the Civil War was a protracted super-spreader event where twice as many soldiers died from disease as from battle wounds. The germ theory of disease would not be established until 1870. Large armies of tens of thousands were in close quarters with no concept of social distancing, regular hand washing, or wearing masks. Thousands died from smallpox despite a smallpox vaccine invented by Edward Jenner 70 years before the war. Many at military camps contracted “camp fever” also known as typhoid fever, but a majority died from gastrointestinal disease spread by poor sanitation and eating and drinking contaminated food and water.

On July 4, 1863, General Ulysses S. Grant defeated the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg, 160 miles north of Port Hudson on the Mississippi River, leaving the Confederates at Port Hudson isolated. On July 9, 1863, after a 48-day battle and siege and no hope of reinforcements, the Confederates at Port Hudson surrendered. The Union forces gained total control of the Mississippi River, one of most important supply routes in the country, and Cailloux’s body was finally recovered after 43 days exposed to the elements.

During the recovery, Cailloux’s body was one of the few to be identified because of a ring from the Society of Friends of the Order, a mutual aid society to which he belonged. Roughly 100 miles northwest of New Orleans, many of the bodies buried at the Port Hudson National Cemetery are unknown soldiers that were beyond identification, their graves have no tombstones and are marked with a short rectangular stone.

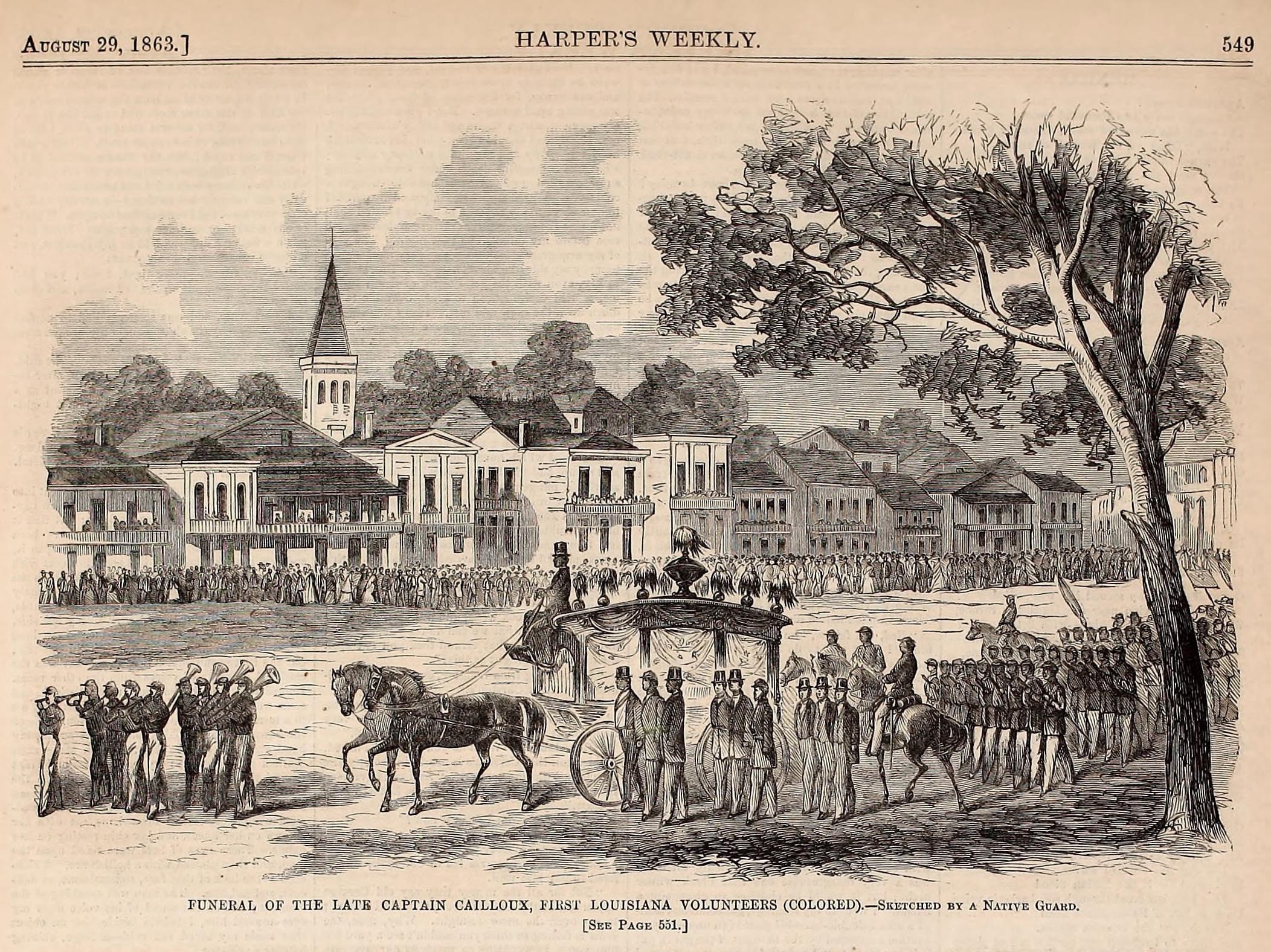

The largest funeral procession the city had seen

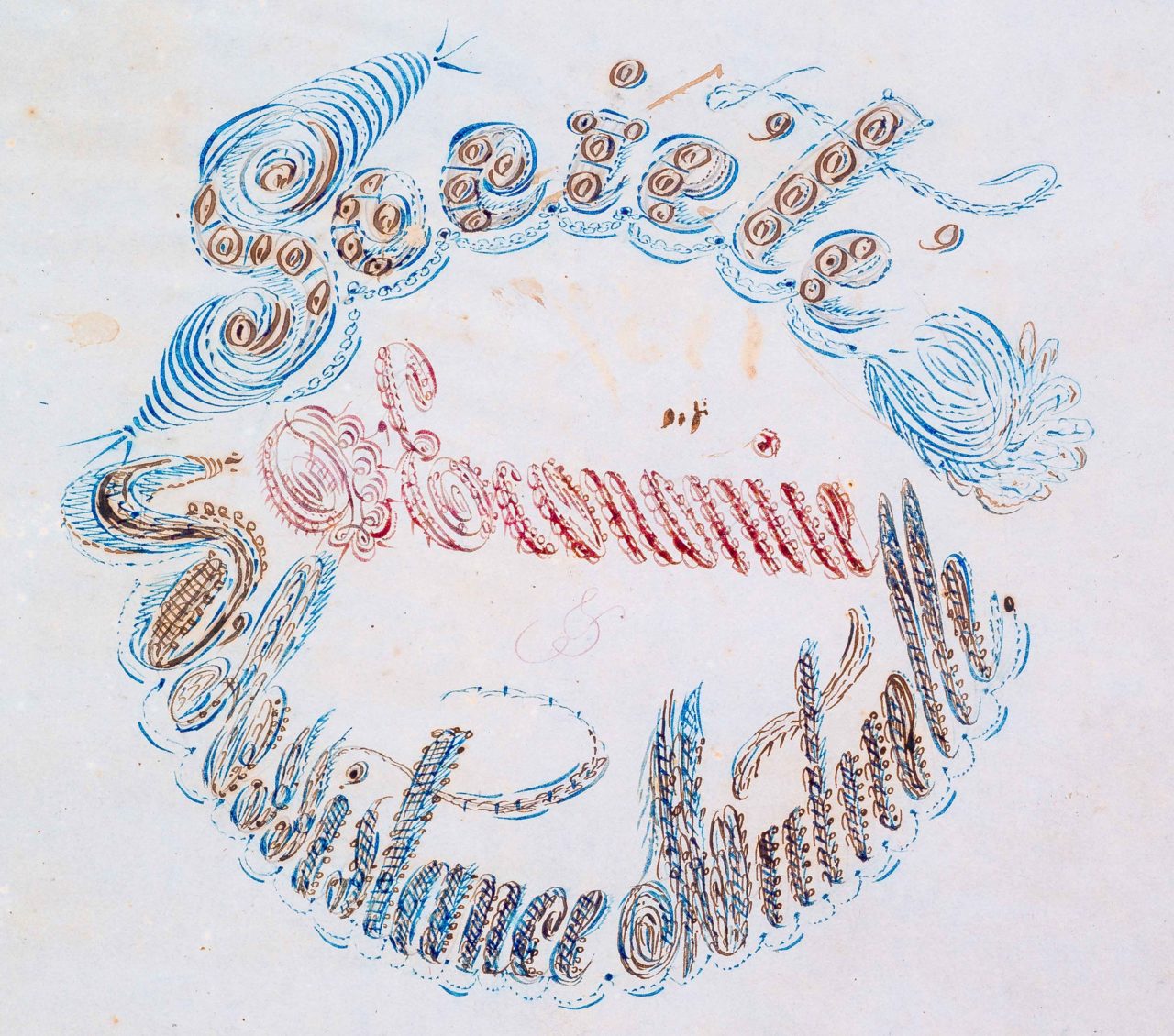

On July 29, 1863, tens of thousands of residents of New Orleans made their presence known for the largest funeral procession the city had ever seen. They lined Esplanade and Claiborne Avenues along the route that ended at St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 at Bienville Street. In addition to hundreds of soldiers, the funeral procession of Captain Cailloux included thirty-seven mutual aid societies with the Société d’Economie et d’Assistance Mutuelle among them. The mutual assistance Société held meetings at Economy Hall in the Trémé neighborhood; and the president, undertaker Pierre Casanave, provided the horse-drawn hearse. Another Economie member acted as a pallbearer of Cailloux’s U.S. flag-draped coffin.

Economy Hall

Many new details of Economy Hall’s history come from Fatima Shaik, a New Orleans 7th Ward native and retired tenured assistant professor from Saint Peter’s University (NJ). Earlier in 2021, she authored the book “Economy Hall, The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood.” [Amazon, Bookshop.org] The book draws from twenty-four handwritten journals mostly in French from the hall’s meetings and gatherings. Years after Economy Hall was sold in 1945, the members finally cleared out the hall and the journals were headed to the garbage when they were rescued by Shaik’s father.

Economy Hall secretary Ludger Boguille, who served intermittently from 1857 through the 1870s, wrote several of the journals. As detailed in Shaik’s book, Boguille was a friend of Cailloux’s wife, Felicie Cailloux, the first principal at the Couvent School. The school was formally known as the Institute Catholique, or the Catholic School for Indigent Orphans, and was located in the Faubourg Marigny. It was the first tuition-free school for African-American orphans in the United States. The school also taught children of free people of African descent for a modest tuition. Boguille taught there with Felicie Cailloux and would run into her husband, André Cailloux, and the couple’s four children at Couvent school fundraisers held at Economy Hall.

Economy Hall was a place for dances, fundraisers, and brotherhood. Shaik said, “By beginning their work in 1836 and continuing for more than a century in the same location on Ursulines Street, the Economie was able to sustain its Black community through enslavement, the Civil War and Jim Crow. They basically established health insurance and employed people from their neighborhoods.”

Economy Hall originates the petition to President Lincoln for Black suffrage

According to U.S. Census figures, the population of New Orleans increased from 102,000 in 1840 to 168,000 in 1860, while the free people of color population declined from 19,000 in 1840 to 11,000 in 1860. Free people of color had some rights, could own land, and run a business, but in the 1850s Louisiana began passing laws restricting the rights of free Black people including proving their status. “When Boguille left his home, he folded thick sheets of paper and put them awkwardly in his vest pocket. . .Without this proof [of his freedom], the police could take him to jail and impose a fine or even a prison sentence,” Shaik wrote, explaining that many free people of color left the country for Mexico or Europe during this time period. In 1857 the Louisiana state legislature voted that enslavement of Black people was a permanent condition. That same year the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that the enslaved Dred Scott was not a citizen and therefore could not sue for his freedom. The infamous court decision drew upon profoundly racist and white supremacist language in its majority opinion including that “[Black people] had no rights which the white man was bound to respect.”

When members of the Black mutual aid societies fought in the Louisiana Native Guards, they fought “first to protect their own homes, their own families, and to improve their condition. And in improving their condition hopefully suffrage, money, land, equality would come; all of the things that the American soldiers get when they fight,” Shaik said.

Veterans at Economy Hall pushed for the right to vote. “The petition for Black suffrage, later delivered to President Lincoln in 1864, was initiated in Economy Hall,” Shaik said.

Cailloux’s death on the battlefield, followed by the heroism of the 54th Massachusetts Black Regiment at Fort Wagner two months later, moved President Abraham Lincoln. He wrote in 1864 about Black war veterans ”who have so heroically vindicated their manhood on the battle-field, where, in assisting to save the life of the Republic, they have demonstrated in blood their right to the ballot, which is but the humane protection of the flag they have so fearlessly defended.”

St. Rose de Lima Catholic Church

Felicie Cailloux also worked with a white Catholic priest, Father Claude Maistre, of St. Rose de Lima Catholic Church on Bayou Road in the 7th Ward. Father Maistre had attended to the needs of the Afro-Creoles including the Louisiana Native Guards that had a military camp within confines of St. Rose de Lima’s parish. This support of the Union led to clashes with New Orleans Archbishop Jean-Marie Odin who supported the Confederate cause.

According to historian Stephen J. Ochs, Father Maistre held a mass reciting the entire text of the Emancipation Proclamation from the pulpit at St. Rose de Lima in 1863. Since New Orleans was under Union control and not in a state of rebellion the Proclamation did not apply to the city and slavery continued. Maistre baptized Black children and placed their names in the same baptismal registry with white children, and he welcomed African-Americans that recently escaped bondage into the church parish. Archbishop Odin viewed these actions as defiant and soon after asked for an interdict, an ecclesiastical censure, and Father Maistre was eventually forced to leave the St. Rose de Lima church.

When Felicie Cailloux asked Maistre to preside over her husband’s funeral mass he did so despite the censure. According to the New York Times, “[Maistre] performed the Catholic service for the dead . . .and delivered a glowing and eloquent eulogy on the virtues of the deceased. He called upon all present to offer themselves, as Cailloux had done, martyrs to the cause of justice, freedom and good government. It was a death the proudest might envy.”

The beginnings of the jazz funeral

Cailloux’s memory became an important rallying cry for recruitment and by the war’s end, a total of 24,000 black soldiers from Louisiana, the most from any U.S. state, offered themselves to the Union army. They were among the 180,000 black soldiers representing 10% of the entire Union Army.

At the front of the funeral procession was the regimental brass band of the 42nd Massachusetts, a white Union regiment that served at Port Hudson and in New Orleans under Major General Banks. The brass band played recently developed valve instruments and played solemn pieces of music.

Library of Congress

Smith, William Morris, photographer

Created / Published

1865

From bugles to “back’ard blasters”

Valves, either rotary or piston, allowed for air to be directed to different sets of tubes on a brass instrument, with the tubes tuned to different scales. Bugles were still used in the military but were limited to five notes of a harmonic scale. The new valve configurations allowed a player to play chromatic scales of 12 notes, like all the black and white keys on the scale of a piano. Because regimental bands were meant to lead an army at the front of procession the early brass instruments had over the shoulder bells that faced backward. Adolphe Sax, who is famous for creating the saxophone, also invented brass saxhorns of different sizes that were soprano, alto, tenor, baritone, and bass, that sounded like the trumpets, trombones, euphoniums, and tubas of today. These early brass instruments became known as “back’ard blasters,” which are visible in a sketch of Cailloux’s funeral procession published in Harper’s Weekly. Black regiments including the 107th U.S. Colored Infantry Band from Louisville, Kentucky also used these instruments as seen in a photograph from 1865.

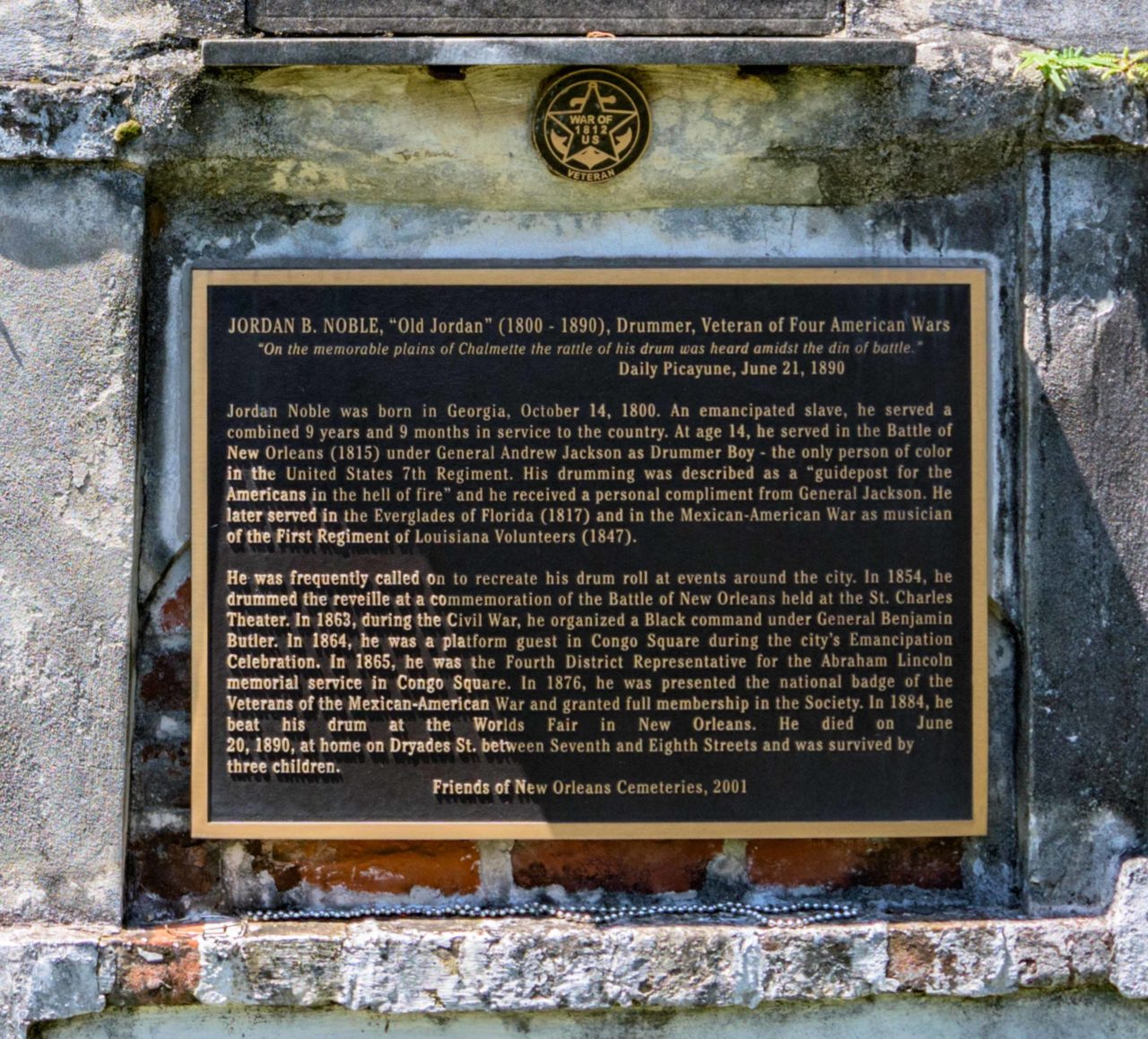

A modern brass band at present day second line parade has instruments that face front, like the Sousaphone tuba invented in 1893, and bands usually form in the middle or back of a procession. Though valve brass instruments were invented in the early and mid-1800s, music including singing and percussion at a “homegoing” had been around since the arrival of Black Africans in New Orleans. A “homegoing” is oftentimes a jubilant celebration of the freedom after death, but it also includes expressions of mourning. The homegoing tradition began when African enslaved people blended their funeral and death rites with the Christianity they were exposed to in America. These celebrations predate jazz music and the term “jazz funeral,” but the two terms have a similar meaning with the celebration incorporating upbeat New Orleans music including jazz, and mournful funeral dirges. Jordan F. Noble, the drummer boy of Chalmette, played at age 14 for General Andrew Jackson during the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 as the only Black member of the 7th Infantry Regiment. After his time in the military, Noble was called upon to drum at functions and funerals while accompanied by a band throughout the 1800s.

On June 11, 1864, Economy Hall’s secretary Bougille helped arrange an Emancipation Jubilee celebrating Louisiana’s 1864 constitution that finally outlawed slavery in the city. The Jubilee had four districts or divisions with grand marshals and paraded with the Union military throughout the city.

“In a March 5, 1875 meeting, [the Economie members] passed a resolution to parade through the streets en masse for every occasion – from celebrations to funerals. They would dress in a way that showed their unity and commitment to equality: black suits and white vests, shirts and cravats with the Economie’s insignia. . . To show that their solidarity had roots in suffrage and in the military units that joined the Union during the Civil War, the Economistes would call people to the streets with the sound of a band,” wrote Shaik in an excerpt from her book. After much debate on how to describe the kind of band. “Someone said, in English, ‘brass band.’”

The number of mutual aid societies grew dramatically after the Civil War. The Young Men Olympian Jr. Benevolent Association, founded in 1884 and the oldest Black benevolent society to still parade, can be seen with up to six divisions with six brass bands during its annual second line. The main division of Y.M.O. Jr. wears black and white suits with their insignia.

The Carnegie Hall of Jazz

Here YMO Jr. members follow the horse-draw hearse of Malcolm John “Mac” Rebennack, Jr. also known as Dr. John (November 20, 1941 June 6, 2019) during a jazz funeral from the Orpheum Theater in New Orleans, La. Saturday, June 22, 2019. Rock and Roll Hall of Famer Dr. John was a worldwide ambassador for New Orleans music blending jazz, funk, blues, pop, boogie woogie, and rock and roll. Photo by Matthew Hinton

Jazz originated in New Orleans with pioneers like Buddy Bolden and Kid Ory in the 1890s and early 1900s. Kid Ory’s band played at Economy Hall and he hired some of the best improvisational jazz players of his day including Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong and Joseph “King” Oliver. Economy Hall became known as the Carnegie Hall of Jazz. The name still lives on with the Economy Hall Tent at the New Orleans Jazz & Heritage Festival or Jazz Fest. The tent features traditional jazz and brass bands interspersed with social and pleasure clubs parading through the audience with feathered fans and umbrellas.

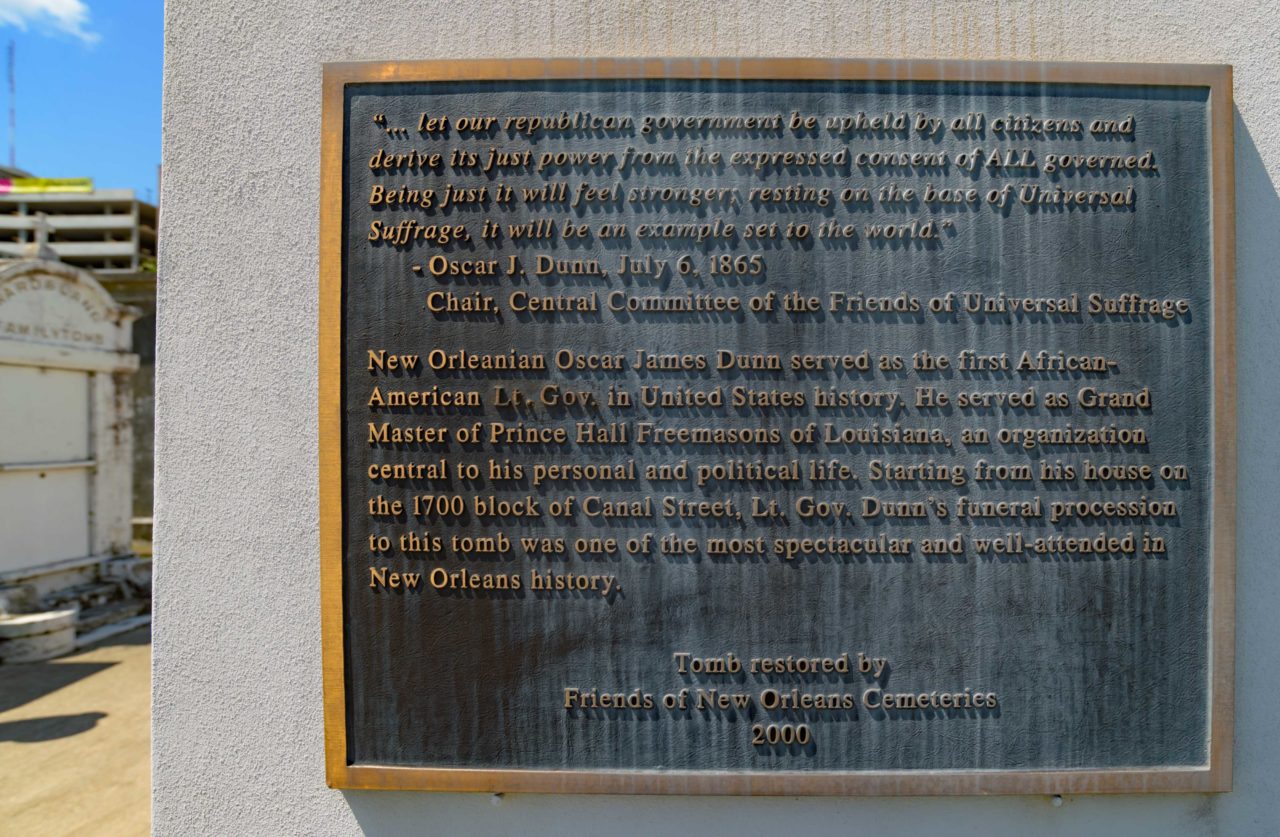

The legacy of Societe d’Economie

Societe d’Economie members and war veterans were also active in politics. The Louisiana Republican Party was actually formed in 1865 in Economy Hall and held its convention there. The Louisiana Republican Party was crucial in the creation of the 1868 Louisiana constitution giving Black people the right to vote and integrating schools. Black voters helped elect Oscar Dunn, the first Black Lt. Governor of Louisiana, the first of any state. His successor P. B. S. Pinchback, a former captain in the 2nd Louisiana Native Guards, later became the first African-American Governor of any state in 1872.

Federal troops withdrew from Louisiana at the end of Reconstruction in 1877, and much of the freedom and equality obtained by Black soldiers and mutual aid societies was soon replaced with segregationist Jim Crow laws, white supremacy, and the disenfranchisement of Black voters until the 1960s.

To justify segregation, history and school textbooks were revised well into the 1960s. “If you were going to say that segregation was right, you couldn’t say that there was unrest or that there were heroes in Black America or Black Louisiana,” Shaik said. “I think that if we don’t learn from history, we repeat it. The idea of erasing what actually existed is a real problem. Whether it happened in the 19th century or whether it’s happening today, facts are facts. We know that people like Cailloux existed. We know that there was a funeral for him with a lot of supporters. We know that the Union won. To ignore those facts would be a disservice to history and to ourselves.”

When Economy Hall was sold, “the benevolent organization was disbanding because it had become obsolete. Twentieth-century Black-owned insurance companies and funeral homes took over the society’s nineteenth-century functions of providing practical and financial support for families during illnesses and deaths,” Shaik wrote. Though most of the societies died out, many social and pleasure clubs dedicated to fellowship and community sprung up in the 1970s-1990s. Today there are over 40 social and pleasure clubs that parade on different Sundays throughout the city bringing music and an air of freedom as people line New Orleans avenues and streets to follow their procession.

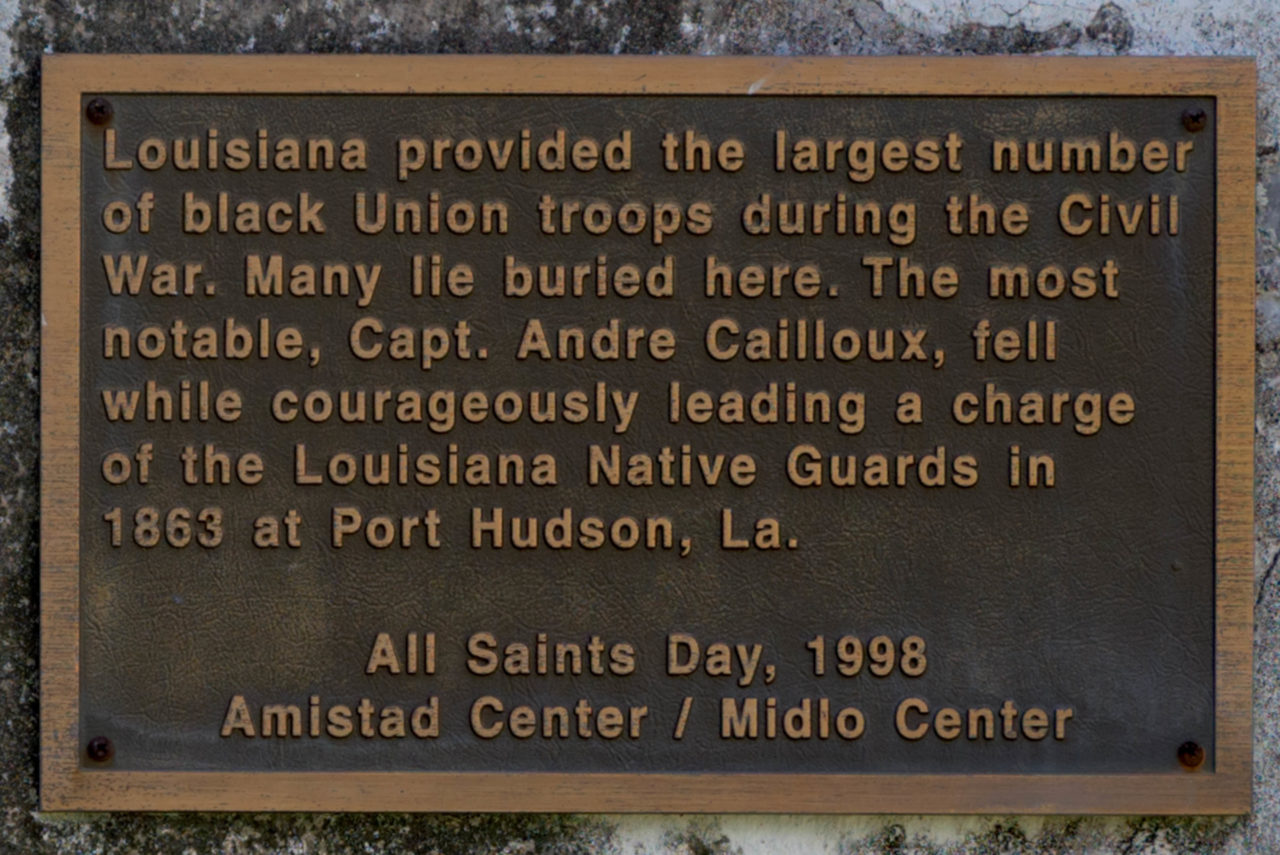

A small triangular park by the former St. Rose de Lima Church on Bayou Road was recently renamed after Cailloux on maps, however, there is no plaque or monument displaying his name there. A small plaque was put up in 1998 inside St. Louis Cemetery No. 2 where he is buried. In 1874, the Grand Army of the Republic, a society of Union veterans of the Civil War, erected perhaps the only substantial monument to Union soldiers in the Greater New Orleans area at Chalmette National Cemetery. Over 100 Louisiana Native Guard soldiers, who were later reorganized as the 73rd Infantry Regiment United States Colored Troops (U.S.C.T), are also buried there. The Latin inscription on the monument reads “Dum Tacent Clamant” meaning “While they are silent, they cry aloud.”

For further information on Cailloux, mutual aid societies, and the Civil War:

Economy Hall: The Hidden History of a Free Black Brotherhood by Fatima Shaik, 2021

https://www.fatimashaik.com/

A Black Patriot and a White Priest: André Cailloux and Claude Paschal Maistre in Civil War New Orleans (Conflicting Worlds: New Dimensions of the American Civil War) by Stephen J. Ochs, 2006

Medical and surgical care during the American Civil War, 1861–1865 by Robert F. Reilly, MD

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4790547/

A 2019 performance of Civil War instruments by the Federal City Brass Band led by Jari Villanueva is viewable on the web. https://youtu.be/YTeNEQEjF8Y?t=11m20s

The 1861 brass piece, “The Vacant Chair,” was known for its the solemn airs, but it is unknown what pieces were played at Cailloux’s funeral.

The Port Hudson State Historic Site is about an hour and half drive from New Orleans.

https://www.lastateparks.com/historic-sites/port-hudson-state-historic-site

Chalmette National Cemetery

https://www.nps.gov/jela/chalmette-national-cemetery.htm