Pittsburgh was a numbers city. Throughout much of the 20th century, people throughout the Steel City played the daily street lottery hoping for one big hit that could improve their economic circumstances. It was seductive: a single nickel or a dime played on three digits could yield a return greater than a week’s pay for many of the city’s general laborers and millworkers. In the summer of 1930, one big hit on the number 805 made heroes out of some Pittsburgh racketeers while others became villains. This story digs into the origins of the city’s gambling rackets and the people and events that made “805” an enduring Pittsburgh legend.

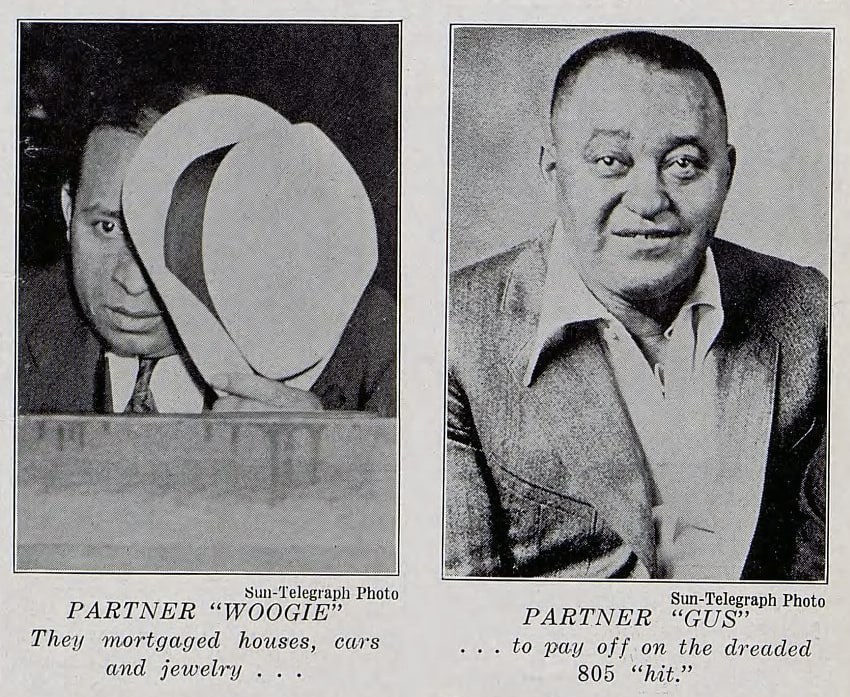

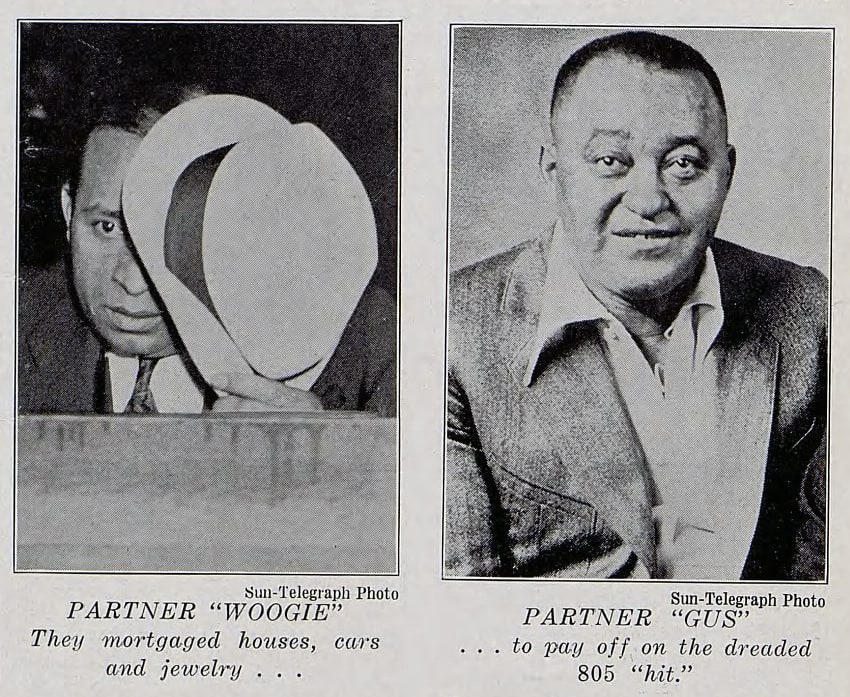

Key players in the Pittsburgh numbers racket

- William “Gus” Greenlee – owner of the Negro League’s Pittsburgh Crawfords baseball team

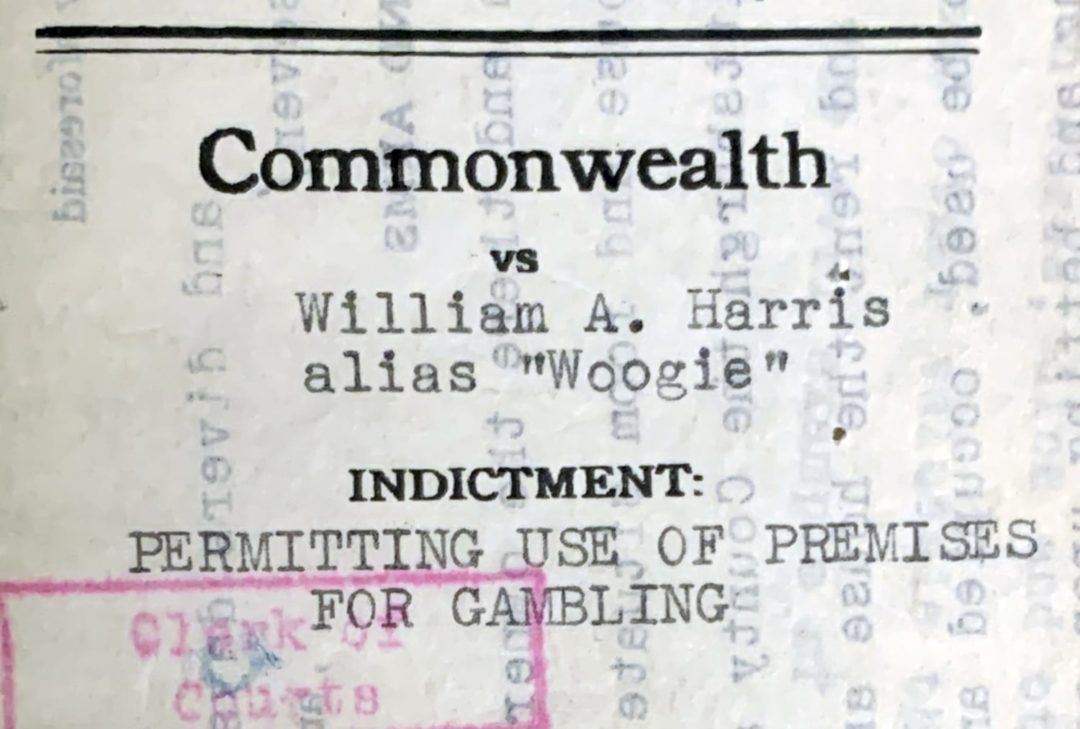

- William “Woogie” Harris – Woogie Harris, older brother of Teenie Harris, was one of Pittsburgh’s most infamous “badmen”

- Jakie Lerner – Numbers banker who was part of a Jewish crime syndicate that was tied to the Mafia.

Lotteries & Numbers Gambling

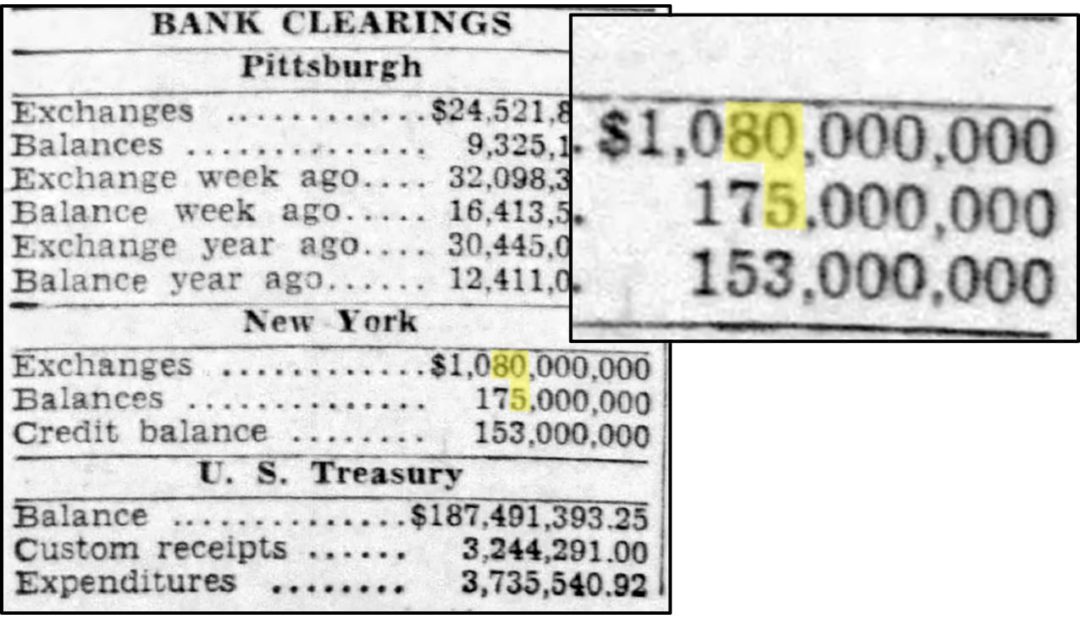

Numbers gambling first appeared in Harlem in the 1920s. It is a street lottery that initially relied upon financial market returns published in daily newspapers. Unlike its predecessor, policy — an easily rigged lottery that used roulette-type wheels and numbered balls drawn from cages — digits for the numbers racket came from two lines of financial data that appeared in every newspaper that published them.

At first, racketeers selected the daily digits from two lines in the New York Bank Clearinghouse returns. The digits chosen were the first two to the left of the millions comma in the first line and the first digit to the left of the millions comma in the second line.

Sam’s Story

Sam Solomon was an aging small-time racketeer with a rap sheet full of bootlegging and gambling arrests when in 1981 he told University of Pittsburgh historian Rob Ruck about the infamous “805” episode of August 1930. Ruck interviewed Solomon half a century after the day when seemingly all of Pittsburgh bet on 805.

Tony Zucco, a numbers writer active in the 1950s and 1960s, worked with Solomon. Zucco’s son Leonard remembers Solomon well.

“He always struck me as just a hanger-on. You know, he really — he was like a gofer,” Zucco said in a 2019 interview.

Zucco recalls that Solomon reminded him of Nehemiah Persoff, the actor who played Jake “Greasy Thumb” Guzik, Al Capone’s accountant, on the Untouchables TV series.

“Me and my brother Tommy used to always … we referred to him as ‘Greasy Thumb Guzik,’” he said.

By the time Ruck had interviewed Solomon, 805 had become one of Pittsburgh’s most popular organized crime stories. Numbers bankers William “Gus” Greenlee and William “Woogie” Harris sprang from its telling as heroic figures who paid off on the bets placed with them. Racketeers like Jacob “Jakie” Lerner who allegedly didn’t pay became the story’s rogues.

📸 Jacob “Jakie” Lerner (center) while serving in the army, c. 1943. Photo in the collection of David Rotenstein.

“805 was a burner. Where the hell is Jakie Lerner?” replied Solomon to Ruck when the historian asked him about 805.

In Solomon’s telling, Lerner was one of the numbers bankers who headed for the hills when 805 broke the bank. It’s a good story that Solomon neatly wrapped inside a catchy rhyme.

The actual story is more nuanced and it marks a key turning point in Pittsburgh’s organized crime history. Greenlee and Harris were two of Pittsburgh’s earliest Black numbers bankers. Many Pittsburghers and historians credit the duo with creating the city’s earliest numbers rackets. Lerner was an Eastern European immigrant who was part of a Jewish crime syndicate that became closely associated with the national group later known as La Cosa Nostra or the Mafia.

Investigating the numbers racket

Betting on financial returns wasn’t new; there had been arrests in Pittsburgh since the 1910s for running lotteries based on clearinghouse returns. What made numbers unique was the standardization.

📸 Daily bank clearinghouse figures published in the Pittsburgh Press August 5, 1930. The highlighted numbers show how 805 was picked.

Within a few years of it spreading through New York City, newspapers throughout the nation began reporting on arrests made in big cities and small towns for running clearinghouse numbers lotteries. Numbers arrests in Pittsburgh began being reported in 1928. Though the word on the street was that Woogie Harris and other Black agents controlled the rackets, law enforcement officials weren’t convinced.

“Investigators hint that they are inclined to believe that those gigantic ‘number’ lotteries, based on the New York clearings are backed by white men and Negroes are acting as agents,” the Pittsburgh Courier reported in 1928 after one of Harris’s first numbers arrests.

August 5, 1930: Betting on 805

805 hit on August 5, 1930. The magnitude of the losses that day spurred widespread speculation about why so many people decided to bet on that sequence of digits.

“This favorite number, 805, figured from the eighth month and fifth day, hit yesterday,” wrote the Pittsburgh Sun-Telegraph.

The Baltimore Afro-American newspaper repeated the date claim and added a new source: a three-digit tip “from a cartoon in one of the morning papers.” One Baltimore columnist, “Bill,” who wrote the paper’s weekly “Numbers Racket” column, the week after 805 hit, boasted, “Just like I told you last week, the winners will come if you string along with me. Two hits in four days!”

When it hit, numbers bankers in Pittsburgh, Baltimore, and other cities scrambled to get their hands on the cash necessary to pay off the bets. “Bill” took credit for the hit: “Just like I told you, last week, the winners will come if you string along with me,” he wrote the next week. “You certainly should have had 102 and 805 because I gave them to you.”

The Associated Press reported more than half of Baltimore’s numbers bankers couldn’t pay. In Pittsburgh, losses were estimated to be more than $400,000. Woogie Harris was vacationing with his family and fellow numbers banker William Snyder and his family in Atlantic City when word reached them that 805 had hit big.

“In the case of one of the Hill pools operated by a Negro, then in Atlantic City, his brother, head of the pool in his absence, wired for instructions when 805 came out,” the Pittsburgh Press reported on August 6, 1930. “The pool’s loss was found to be $101,000.”

The 805 episode firmly established Greenlee and Harris as Pittsburgh’s leading numbers racketeers. “Their numbers trade grew to impressive dimensions,” wrote historian Ruck in his 1993 book, Sandlot Seasons.

Sam Solomon’s version of the 805 episode brings together all of the key players and factors that made numbers such an important part of daily life in Pittsburgh for most of the last century. It captures the significance of the city’s Black gambling entrepreneurs and it exposes some of the fault lines that emerged in the early 1930s as white racketeers began gentrifying the numbers by displacing the African Americans who established the game and who taught newcomers like Lerner how to run it.

Gus Greenlee & Woogie Harris – Pittsburgh’s “badmen”

Pittsburgh’s early Black gambling entrepreneurs introduced the numbers to Pittsburgh in the mid-1920s. William A. “Woogie” Harris was one of four men historians like Ruck credit with introducing numbers to Pittsburgh. His contemporaries and other innovators included Gus Greenlee, Richard Gauffney, and William Snyder.

Greenlee and Harris got rich off their numbers business. Both men bought large suburban homes in 1929 in Pittsburgh’s East End. Their generosity through feeding the poor during the holidays and for providing the capital to Black entrepreneurs unable to borrow from banks added to their status among Pittsburgh’s African Americans.

Greenlee and Harris had become Pittsburgh’s sublime “badmen”: heroes in the Black narrative tradition who break laws and rules competing against the odds to come out on top. Badmen are outlaws who revel in antagonizing order, according to historian Lawrence Levine. They are fictional, like Stackolee, and real, like Greenlee and Harris or Harlem’s Stephanie St. Clair, who famously stood her ground when mobster Dutch Schultz began taking over New York’s numbers.

William “Woogie” Harris, Teenie Harris’s older brother

📸 Woogie Harris and Gus Greenlee. Photos published in the Bulletin Index, February 20, 1936. Credit: historicpittsburgh.org.

“Woogie” Harris was a native Pittsburgher. Born in 1896, Harris grew up in the Hill District, a densely settled neighborhood chock full of immigrants: Blacks from the Deep South, Eastern European Jews, Italians, and Syrians. The second of three children, Harris grew up surrounded by Black entertainment and hospitality entrepreneurs. His mother ran a boarding house that grew into a hotel business.

George Harris, an older brother, who later helped run the family’s hospitality businesses, as a child repeatedly mispronounced his younger brother’s name.

“So here, in N.Y., [Chicago] or all parts east and west, the name ‘Woogie’ has stuck to Pittsburgh’s popular sportsman,” Pittsburgh Courier columnist Chester L. Washington wrote in 1939.

Woogie’s younger brother, Charles “Teenie” Harris, began life doing odd jobs for the family businesses, including running numbers, before becoming an internationally acclaimed photographer.

Woogie Harris’s earliest solo business ventures included billiards halls and a barbershop. Poolrooms and barbershops were popular third places in Black neighborhoods: joints where folks could relax, play, and exchange information. They also became convenient places where people could buy a number.

Harris opened his Crystal Barbershop on Wylie Avenue, a congested street filled with Black-owned businesses that became the neighborhood’s cultural hub known first as “Swing Alley” and later, “the crossroads of the world.” His family’s Masio Hotel was one block over and across the street, in 1933, Gus Greenlee opened the Crawford Grill No. 1.

📸 1948 Allegheny County indictment of Woogie Harris for violating the state’s anti-lottery laws.

Gus Greenlee, owner of the Pittsburgh Crawfords

William A. “Gus” Greenlee was born in 1893 in North Carolina. He rode the rails to Pittsburgh in 1916 during the Great Migration of Blacks moving north to escape Jim Crow. After fighting in Europe during World War I, Greenlee returned to Pittsburgh and went into bootlegging. His first known run-in with the law was in 1921when he was charged with receiving stolen goods.

In 1924, Greenlee and singer and sports promoter Thomas “Kid” Welch bought a Wylie Avenue nightclub. Their Paramount Inn quickly became one of the city’s top black and tan clubs: a place where Blacks and whites could dance to the latest music, jazz. By the end of 1930, Greenlee owned or had substantial stakes in several Hill District restaurants, nightclubs, and pool halls. Within a decade, he gained widespread fame as the owner of the Negro League’s Pittsburgh Crawfords baseball team and managing professional boxers.

Also by that time, Greenlee and Harris had become the undisputed leaders of the city’s Black gambling syndicate. The Pittsburgh Courier that year called them the “Negro overlords” of the Hill District’s numbers rackets. The pair employed hundreds of runners and writers who operated throughout the city and they used their legitimate businesses fronts in thinly veiled attempts to conceal their vice operations.

After 805

The 805 hit forged lasting reputations and organized crime networks throughout Pittsburgh and neighboring cities and counties. In 805’s wake, fortunes and reputations were made and lost. Jewish and Italian racketeers who survived 805’s hit on the city’s numbers banks also bounced back. Racketeers like Jakie Lerner, Harry “Kid” Angel, and Frank “Froy” Nathan used the tricks they learned from their earlier partners like Greenlee and Harris to build their own gambling networks with links to the Cleveland and Detroit mobs. These Jewish mobsters’ reach included controlling some of the earliest casinos in Las Vegas and extensive South Florida gambling rings.

Did you know that you can watch Very Pittsburgh shows on your TV?

📺

Grab the Very Local channel on Roku, Amazon Fire and Apple TV to watch all of our shows for FREE.

Looking for more Western Pennsylvania mob stories?

Journalist and historian Russel Shorto grew up in Johnstown Pennsylvania. He recently wrote a book, “Smalltime: A story of my family and the mob” [Amazon, Bookshop.org] about his grandfather’s involvement in the mafia in Johnstown.

Additional Resources

- David Rotenstein. “The Numbers Banker’s Safe.” Blog. Heinz History Center (blog), August 5, 2020. https://www.heinzhistorycenter.org/blog/western-pennsylvania-history/the-numbers-bankers-safe.

- Robert Ruck. Sandlot Seasons: Sport in Black Pittsburgh. Illini Books ed. Sport and Society. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1993. [Amazon, Bookshop.org]

- Mark Whitaker. Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance. Simon & Schuster hardcover edition. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018. [Amazon, Bookshop.org]