Editor’s note: This is a two-part story. JaQuay Edward Carter is the founder of the Greater Hazelwood Historical Society and the BLACK HISTORY SOCIETY of Western Pennsylvania. Mr. Carter has a ton of great information on Pittsburgh history and first learned about Ajax Jones when he was researching some local family history. Be sure to check out part 1 of this story to learn more about the early life of Ajax Jones.

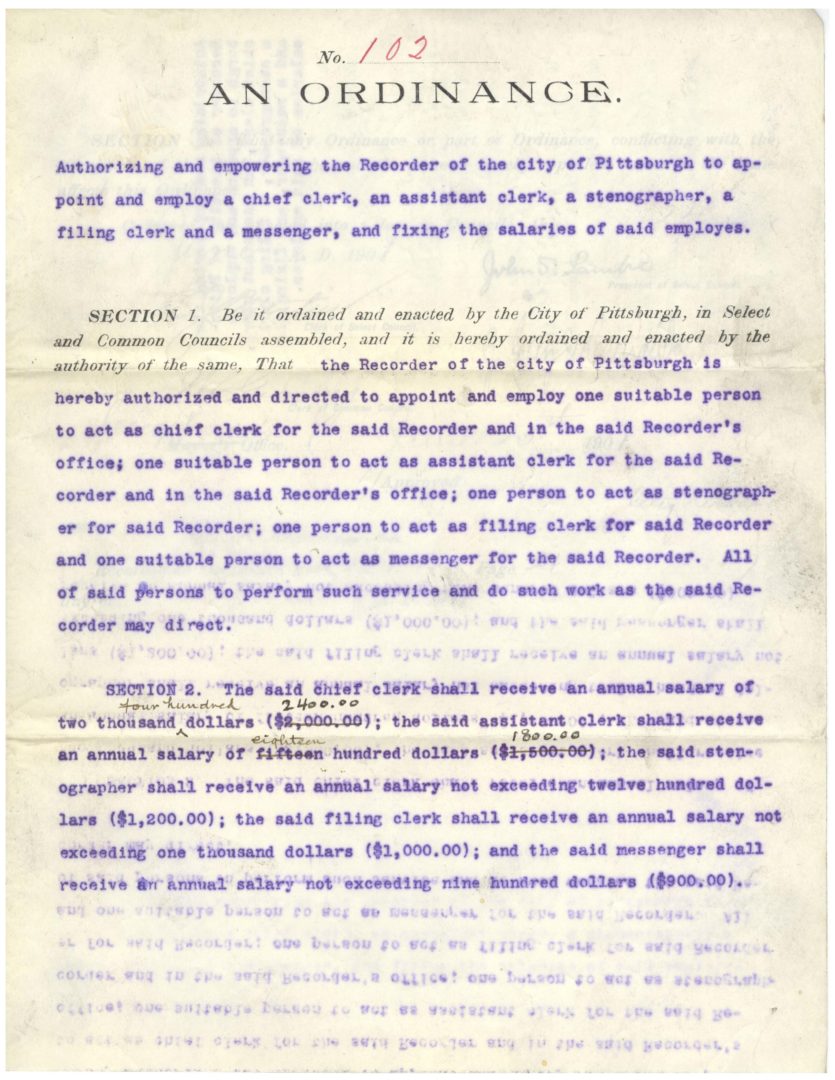

Ajax began his career in public service in 1878 when he was appointed as a messenger for Mayor Robert Liddell. This made him the first African American executive in the city of Pittsburgh. The term messenger is likely equivalent to an advisor. The messenger was a paid position. The mayor’s messenger assisted with delivering communications and facilitating meetings.

From there, he quickly rose in political power and prestige. Ajax presided over numerous political organizations in the Hill District, such as the Don Cameron Club, as well as being elected Captain of the Grand Central Marching Band. Everybody called him “Captain” Ajax. That respected title proudly followed him around wherever he went. He was a staunch supporter of the Grand Old Republican Party of Lincoln. Ajax made quite a reputation for himself as the city’s leading Black politician and orator.

The Pittsburgh Daily Post reported on Aug 21, 1888:

“Now Ajax Jones kicked down his trouser leg and buttoned up his Prince Albert and stepped up to the forum. Master of Ceremonies Foster had announced him, and the little Napoleon bowed his head to allow the audience to applaud. The storm was of short duration and the great Ajax began: “My people, the dusky sons and daughters of Africa’s burning sands is here celebratin’ their freedom. Abe Lincoln signed the papers and we’re here enjoying liberty. Just like it was in Egypt, God said let my people go and we went.” His words were met with a “thunderous round of applause which echoed throughout the Allegheny Valley.”

Anyone who ever had the pleasure of seeing him in action had to agree that “now since John Wilkes Booth is dead, Ajax has few equals as an actor.” Another Pittsburgh newspaper reported, “It will cost us $900 a year to keep Ajax Jones in the mayor’s office, but we must have Ajax at any price!” By the way, $900 is equivalent to about $25,000 today. Ajax walked and talked with “statesmen” for many a day. He used his position at the mayor’s office to intervene on behalf of Black people. He often put in a good word or vouched for those he personally knew well. Ajax was known to accompany his friends to court, acting in the capacity of “bodyguard.” The judge found it hard to keep a straight face in his dealings with Ajax. The amicable relationship between the two made it easy on the accused. In 1895, the Hill District’s Republican headquarters, Lafayette Hall, was torn down. Ajax, popularly known as “the modern Demosthenes,” tearfully lamented: “Fare thee well…If forever, still forever, fare thee well. Though you crumble to dust, remember that I remain. In my hands your glory will not fade, nor your fame tarnish…bright oasis in the desert of the past, fare thee well…” This show of impassioned eloquence, coming straight from the heart of one of the city’s brightest intellectual stars was received, not with applause, but with a deafening silence – much more impressive.

His messengership would continue through nine successive mayoral administrations, including

- Robert W. Lyon (1881-1884)

- Andrew Fulton (1884-1887)

- William McCallin (1887-1890)

- Henry I. Gourley (1890-1893)

- Bernard J. McKenna (1893-1896)

- Henry P. Ford (1896-1899)

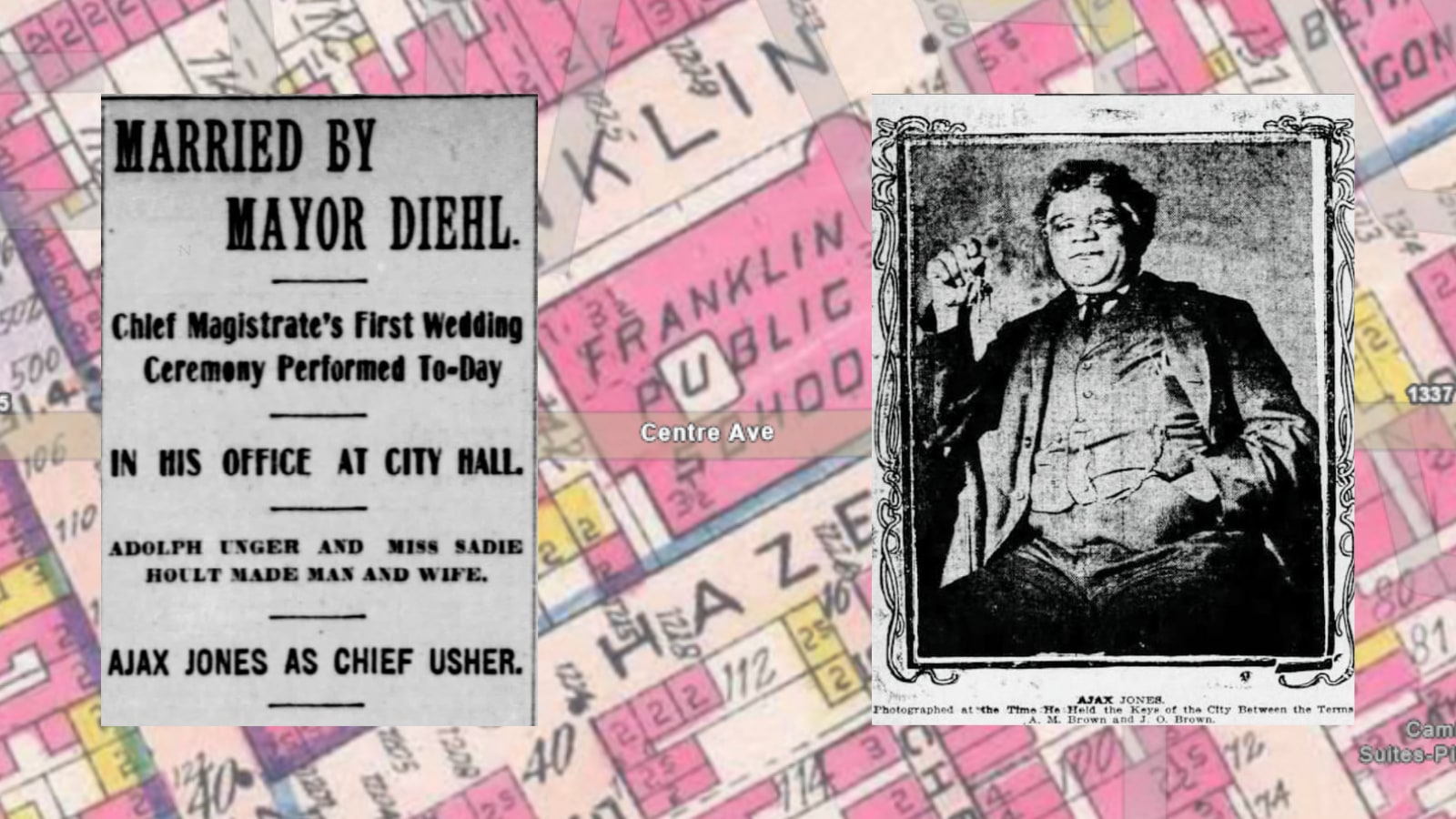

- William J. Diehl (1899-1901)

It was said that “When the mayors went on business and pleasure trips, the city was turned over to Ajax’s care, and no potentate from the dark continent, who may have been among his ancestors, ever carried a heavier burden of dignity and responsibility…” That was when he earned the honorary title of “Mayor” Ajax. He was ahead of his time and could have very well been Pittsburgh’s first black mayor.

Ajax Jones holds the keys to the city between mayorial administrations

Ajax Jones served as a messenger for nine consecutive mayors and has had the distinction of being recorder for a few days. Ajax Jones served as chief executive to the city of Pittsburgh during the three days and seven hours between the removal of Mayor Adam Brown and the introduction into the office of Mayor Joseph Brown. In May 1901, a commonwealth reorganization changed the title of Mayor to Recorder, so that’s why Adam Brown was put out of office. Ajax was technically “recorder” for three days and seven hours, but that was essentially the same as being Mayor. By 1903, he was known as “the best messenger in all of the United States.”

It was time for messenger reappointment in 1904. Ajax said of this time in his own words:

“Why shouldn’t I get the appointment?” asked Jones, “the mayor of the Negro vote,” in discussing his application last night. “I have served as messenger for seven mayors of this great municipal corporation. I have seen men come into and then go out of politics. I have served the mighty and the small. I have served all of them well. I was the only Negro executive the city of Pittsburg has ever had. For three days and seven hours I was, to all intents and purposes, the mayor or recorder of this great municipality. I had the keys: I held the office silent and alone.” [Pittsburgh Daily Post June 15, 1904]

“Mayor” Ajax would not be so lucky this time around. He would never be appointed as messenger again. His time in the mayor’s office might have run out, but he had already left an indelible mark on the city. Ajax was certainly the pride of his people and a credit to his race.

Life after city hall

Soon after, he was appointed as a South Side police captain. He would go on to become deputy sheriff of Allegheny County in 1907, only the second African American to be appointed to the force of deputies since Paul J. Carson in the 1870s.

![[Ajax Jones Keys to the City - The Pittsburgh Press February 22, 1903]](https://verylocal.com/wp-content/uploads/migration/51/f828eed8-charles-avery-ajax-jones-2.jpg)

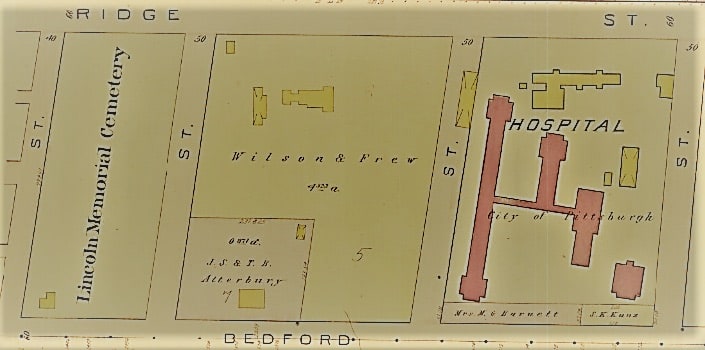

Lincoln Colored Memorial Cemetery in the Hill District

By 1913, he was retired from a half-century of life in the political arena. It had been a decade or so since the “invincible” and “immortal” Ajax wielded considerable influence among the residents of the Hill District. He became superintendent for the Lincoln Colored Memorial Cemetery and a majority stockholder. He took special care for what was considered the best graveyard for Black people in the city. That hallowed ground on Bedford Avenue was established at the close of the Civil War as the only cemetery for colored dead in mid-19th century Pittsburgh.

The cemetery was just a stone’s throw from where Charles Avery “Ajax” Jones drew his last historical breath. He died at age 77 on May 19, 1928, from “paralysis agitans,” which is better known today as Parkinson’s disease. “Mayor Ajax” was buried at his beloved Lincoln Cemetery on Bedford Avenue. A decade later, in 1938, plans were made to relocate the 85-year-old, 4-acre cemetery to make way for Bedford Dwellings – Pittsburgh’s first low-income housing project. More than 100 Black veterans from the Civil War, Spanish-American War and World War I were laid to rest here. Estimates varied from a few hundred to 4,000 or more graves being removed from the cemetery. It was situated near Greenlee Field, to other area burial grounds (mainly Woodlawn Cemetery in Wilkinsburg).

The Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported on Nov. 10, 1938, that “Among the graves for which the colored community here has great respect are those of Ajax Jones. He was a messenger in the Mayor’s office in the 1870s and the first person of color to be employed at City Hall. It was also reported that he owned important Downtown and Hill District real estate.” His final resting place would be at the historic Greenwood Cemetery in Sharpsburg. He is now buried among some of Pittsburgh’s most notable people, including Henry J. Heinz and Pulitzer-prize-winning playwright August Wilson.

If I could say one thing to the “Mayor,” I would say: Fare thee well, Ajax…Though you crumble to dust, remember that I remain. In my hands, your glory will not fade, nor your fame tarnish…bright oasis in the desert of the past, fare thee well.”