Inside Pittsburgh International Airport’s Concourse A is a Black history museum. Just a few steps away from Gate A6, travelers can browse inside the tribute to Western Pennsylvania’s Tuskegee Airmen. Visitors can read about the Black aviators’ role in history and what they did after their service. There’s a lot to take in and you could be forgiven for overlooking the final entry in the “After the War” panel: “Harold Slater, proprietor, Crystal Barbershop.”

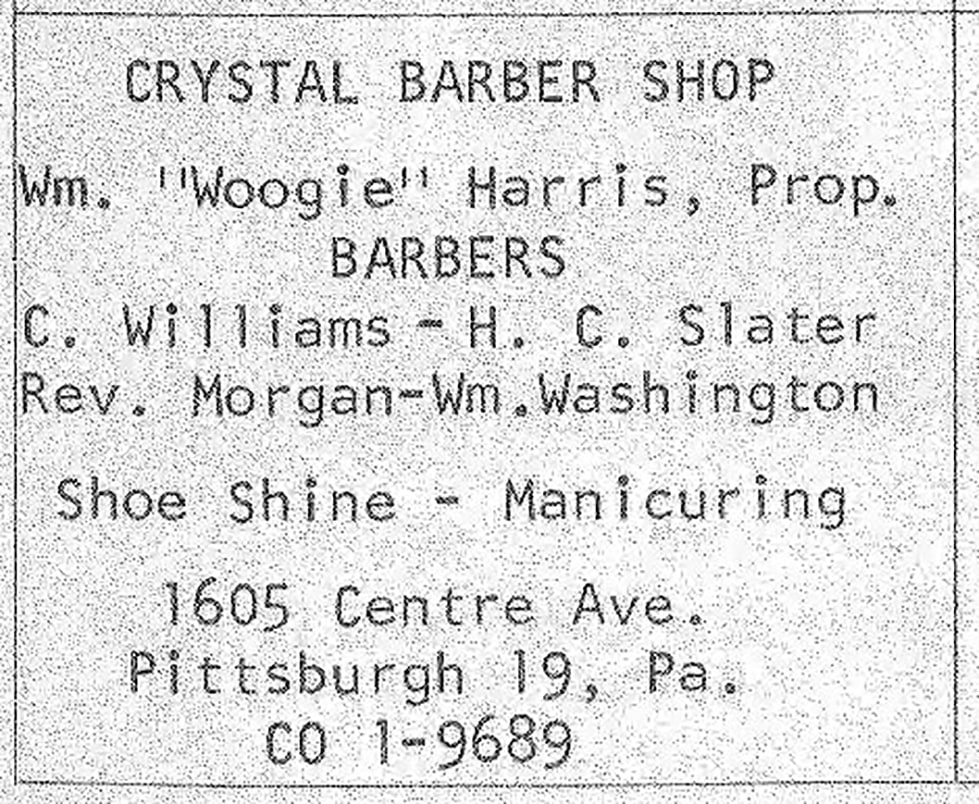

The Crystal Barbershop might have been Pittsburgh’s best-known tonsorium. Its owner, William “Woogie” Harris, was a legendary gambling baron and one of the city’s wealthiest Black entrepreneurs. Harold Slater was his friend, son-in-law, and successor in the iconic Hill District establishment. Slater’s story begins more than a century ago in rural Virginia and it continues today with his daughter’s Bloomfield barbering business. It’s a distinctly Pittsburgh story that reveals the complexity of Black life and entrepreneurialism in the Hill District during the twentieth century.

Part of the Great Migration

Claude Slater owned a barbershop in rural Luray, Virginia. His father also was a barber. The family moved to Pittsburgh in 1920 or 1921 and they settled in a rented brick house in the Northside. Born in 1924, Harold was one of Claude and Helen Slater’s three sons. One son drowned at age 17 in 1934 and Helen died a few months after Harold’s birth. Claude remarried and the family moved to Centre Avenue in the Hill District where he continued barbering.

Barbershops were vibrant hubs in Black communities. They were places where stories were told, jokes were swapped, and business was done — not all of it cutting hair and shaving. Writer Melissa Harris-Perry once described Black barbershops and beauty parlors as safe spaces where members of the Black community could speak and act freely, places “where nothing is out of bounds for conversation and where the ‘serious work of figuring it out’ goes on.”

Harris might have been Pittsburgh’s best-known barber — not for his mastery of the clippers & razor, but for his role as one of the city’s most storied racketeers. He opened the Crystal Barbershop on Wylie Avenue in the Hill District in the 1920s. Over the years, barbers came and went from his six-chair shop. Harold Slater was one of them. He became Woogie’s close friend and, for a time, was married to Woogie and Ada Harris’s daughter, Marion.

Harold Slater was 19 when he enlisted in the army in 1943. He became an airplane mechanic with the Tuskegee Airmen. A modest man, Slater’s family only found out decades later.

“My dad, the Tuskegee Airmen, he never talked about that,” Michelle Slater said in a June interview. The family only learned about his service in the unit after they were contacted by Tuskegee Airmen historian and journalist Regis Bobonis.

After the war, Slater returned to Pittsburgh where he got a job with the city’s sanitation department. For decades, he worked an early morning shift picking up garbage in Bloomfield and other neighborhoods. Evenings and Saturdays, he cut hair in the Crystal Barbershop.

Did you know that you can watch Very Pittsburgh shows on your TV?

📺

Grab the Very Local channel on Roku, Amazon Fire and Apple TV to watch all of our shows for FREE.

Part of the Family

Harold Slater married Marion Harris in 1951. Marion had been married and divorced once before; it was Slater’s first time at the altar. After the couple wed, they lived in the third-floor apartment in the Harris mansion on Apple Street in Homewood, now known as the National Negro Opera Company House.

Both Harold and his brother John had worked in the Crystal Barbershop on Wylie Avenue. John, like his father, also worked as a Pullman porter “redcap.” In the 1950s, John left the Crystal and opened his own barbershop on Frankstown Avenue with his father. Harold stayed at the Crystal with Woogie Harris.

Harold and Marion Slater’s marriage began disintegrating after about five years. In 1957, Marion was involved in an affair with an Apple Avenue neighbor and the couple were seriously injured in a car accident after reportedly leaving a motel near Monroeville one evening. That relationship resulted in the birth of a daughter, Vicki.

The Slaters’ divorce became final in late 1958 and a few weeks later Harold married Dolores Smith. Dolores was a Pittsburgh native whose family had moved to the Steel City from Florida. Dolores also had been married and divorced once. Her mother, Louise, had been involved with Woogie’s older brother, George, for more than a decade in the 1930s and 1940s. Though the pair never wed, city directories listed them as a married couple and a Teenie Harris biography described her as George’s common law wife.

Dolores Slater, now 93, doesn’t think her mother and George Harris were in the numbers business together.

“She wasn’t into numbers then. After she left George, that’s when she became independent, and I guess started to get into the numbers,” she said in an August interview. “I think George had dabbled in the numbers, too, with his brother.”

For more on Pittsburgh’s Black history, including more about the hill district, check out “Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance” by Mark Whitaker. [📚 Amazon, Bookshop.org & local bookstores]

Louise and Snotty Make Their Mark

After splitting with George, Louise struck out on her own for a few years before teaming up with Charles Lewis. Growing up in the Hill District, Lewis had a perpetually runny nose and it earned him the lifelong nickname, “Snotty.” Lewis enlisted in the Army in World War II and he distinguished himself in battle in Europe. More than 50 later, then-Sen. Rick Santorum (R-Pa.) intervened to get Lewis the Bronze Star he had earned in the war.

Louise and Lewis were already a pair when her daughter celebrated her 18th birthday at the Crawford Grill No. 1 in December 1945. Teenie Harris captured the event in a photograph that is now archived at the Carnegie Museum of Art. The couple married in Cumberland, Maryland, in 1948. One year earlier, their arrests at the smoke shop at Wylie Avenue and Crawford Street that they ran as a front for their numbers business began making headlines.

The couple first lived at 423 Grove St. before moving to Center Avenue, where they owned a house. Louise filed for divorce in 1951. Though no decree was ever issued, Charles transferred the title to their home to Louise and he moved out.

Louise didn’t skip a beat and she continued her lucrative career as a gambling entrepreneur.

“My mother was a writer.” Dolores said. As her mother’s health declined in the late 1950s, Dolores would use her lunch breaks to turn in her mother’s bets to Tony Grosso. “She wrote numbers for Tony.”

LEARN MORE: A big numbers hit in 1930 created Pittsburgh mob legends

Dolores had gone to work as a secretary at U.S. Steel in 1952. Her story is a Pittsburgh civil rights milestone in its own right.

“I got a job with U.S. Steel, the first Black girl,” she said. Though Slater broke the company’s clerical worker racial barrier, she still experienced racism. She vividly recalled two events. The first was when her boss ordered her to cancel a wedding shower for a white colleague at her Hill District home. The second was when she was told to not eat with a Black janitor in the company cafeteria. She resisted both times and continued working there until 1959 after she got pregnant with her first daughter.

The Crystal Barbershop’s Many Lives in the Hill District

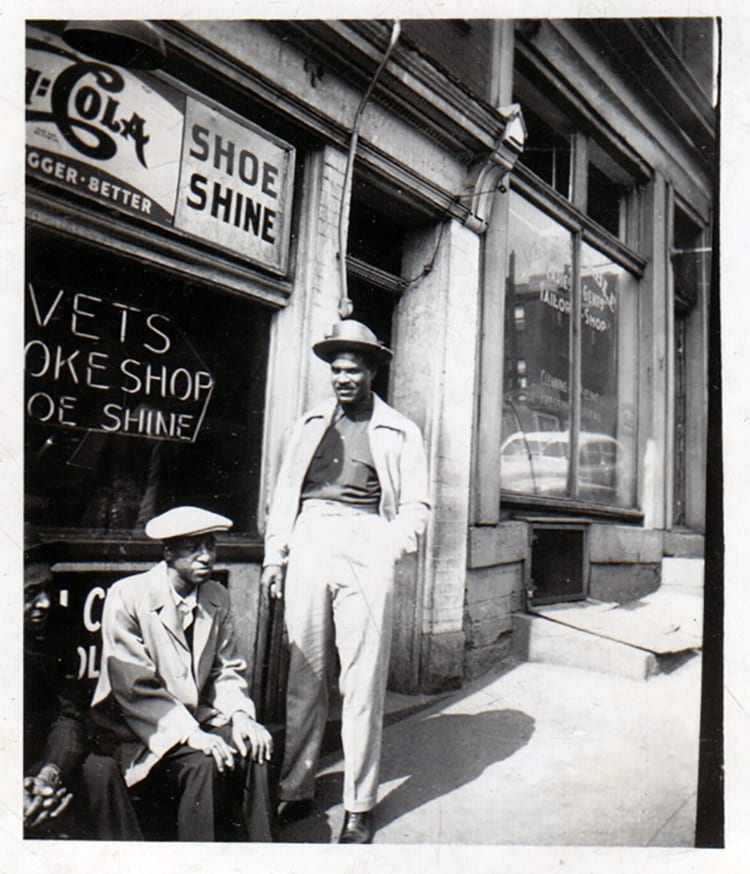

In 1958, robbers broke into the Crystal Barbershop and the Pittsburgh Courier identified Harold as its manager. After Urban Renewal displaced the shop from Wylie Avenue to Centre Avenue, Harold moved along with his now former father-in-law, Woogie Harris, to a new Centre Avenue location.

The shop’s new location was next door to one of the city’s most popular nightspots, known for its music and feisty owner, Anna “Birdie” Dunlap.

“The Hurricane was one of the jazz clubs. Everybody came to the Hurricane,” Dolores said. “A lot of men would go to the barbershop first and then they’d slide right over to the Hurricane and spend the rest of the evening.”

Like its predecessor on Wylie Avenue, the Centre Avenue Crystal Barbershop also was a numbers drop. Though Harold Slater never got into that particular family business, he could be trusted to hold money for the shop’s gambling entrepreneurs, his widow said.

Harris died in 1967. Ada Harris inherited the lease and Woogie’s shop’s contents, but Harold continued to manage the barbershop.

“He worked there from the time [Michelle] was born until she was in her twenties,” Dolores Slater said.

“The Crystal Barbershop had closed down and then daddy went up with his brother,” Michelle Slater said.

And then the city’s urban renewal machine again caught up with the Crystal: “This used to be the ghetto but it’s not anymore. Crawford Square then moved in all up here,” said Dolores Slater.

John Slater’s barbershop, Slater’s, was at the corner of LaPlace and Kirkpatrick farther up in the Hill District. John died in 1988 and Harold eventually moved his business into the family home’s garage. There, his daughter Michelle joined him in his two-chair shop.

“We did hair in the shop down in the basement for 26 years,” Michelle said in June. “I’ve just been doing it on the side. So big-scale, the last five years is when I really started out into the public.”

The Modern Crystal Barber

Michelle, 58, grew up in the Hill District. After graduating from Brashear High School, she attended the University of Pittsburgh. Slater worked in retail and real estate before landing a job in the District Attorney’s office. Now she works for the state as a casino compliance representative and she owns the Crystal Barber, which operates out of Bloomfield’s Sola Salon. Following in her father’s, uncle’s, and grandfather’s footsteps, Slater said, “I’ve always had two jobs, worked two jobs. I’m my dad’s busy beaver.”

After learning the trade from her father, Michelle Slater got the formal training she needed to get a license. She beams when speaking about the tradition she’s continuing.

“Even though I have the skills of doing all kinds of hair, I didn’t just want to do female hair,” Slater said.

She’s proud of her lineage and continuing in the trade her father, uncle, and grandfather practiced: “When people post things or see me and they always tell me, ‘Your dad would be so proud of you.’”

Michelle has lots of stories about her father. One perfectly captures what it was like growing up in the barbering tradition.

“When you grow up in a barbering family, everybody has to look good. You can’t look shabby,” Slater said. “You have to look neat, so that was the pet peeve and that was the thing.”

Michelle and her sister Kim had to remind their dates to remove their hats before coming over to the house.

“I mean that was the one thing with my dad, like ‘I don’t care who you date, just tell them they cannot come in this house with a hat on,’” she said.

Steeped in history and tradition, Michelle is passionate about her family’s story and its place in Pittsburgh history. Her shop has an “ancestry wall” where she keeps artifacts from her father’s shop and family photos that tell a story about a century of barbering in Pittsburgh’s Hill District.

“Our family is rich — I mean we’re rich with history,” Slater said. “This is our hustle. This is what we do. My mother never wanted to leave the Hill and I’m glad she didn’t.”

Additional Resources

- Cheryl Finley, Teenie Harris, Laurence A. Glasco, and Joe William Trotter. Teenie Harris, Photographer: Image, Memory, History. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press : published in cooperation with Carnegie Museum of Art, 2011. https://artblart.files.wordpress.com/2012/03/teenie-harris-book.pdf.

- Laurence A. Glasco and Federal Writers’ Project (Pa.), editors. The WPA History of the Negro in Pittsburgh. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2004. [Amazon]

- Melissa V. Harris-Perry. Barbershops, Bibles, and BET: Everyday Talk and Black Political Thought. Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 2004. [Amazon]

- Jacobs-Huey, Lanita. From the Kitchen to the Parlor: Language and Becoming in African American Women’s Hair Care. Studies in Language and Gender. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press, 2006. [Amazon]

- Mark Whitaker. Smoketown: The Untold Story of the Other Great Black Renaissance. Simon & Schuster hardcover edition. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2018. [Amazon, Bookshop.org]