Jackie Wallace was ready to jump. In 2014, far removed from his glory days as a defensive back for the Minnesota Vikings, he walked the steep incline of the Pontchartrain Expressway onramp towards the “Pelican Bridge,” what the original span of the Crescent City Connection that crosses the Mississippi River to the Westbank was known by older locals. A lifetime of perceived and actual failures weighed heavy on Wallace, and years of bone-crushing hits and hard drug use left him feeling frail and despondent. A couple of hundred yards away, Ted Jackson, a longtime photojournalist with The Times-Picayune, was on assignment, photographing a Curtis P-40 Warhawk as it was set into place at the World War II Museum. Twenty-four years earlier Jackson and Wallace’s lives became inextricable. If Ted had stepped outside they might have seen each other. Maybe felt each other’s presence. Maybe they did — because Wallace didn’t jump that day — and Jackson didn’t have to run to the river to photograph his demise.

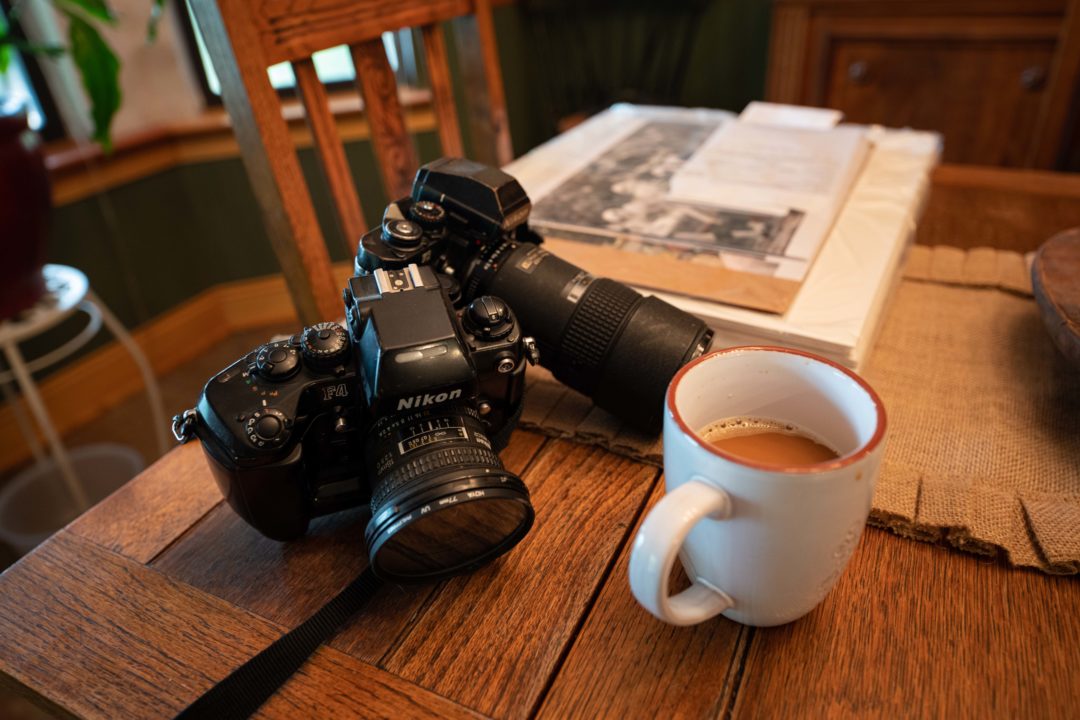

“These might be the two cameras I used when Jackie and I first met,” said Jackson.

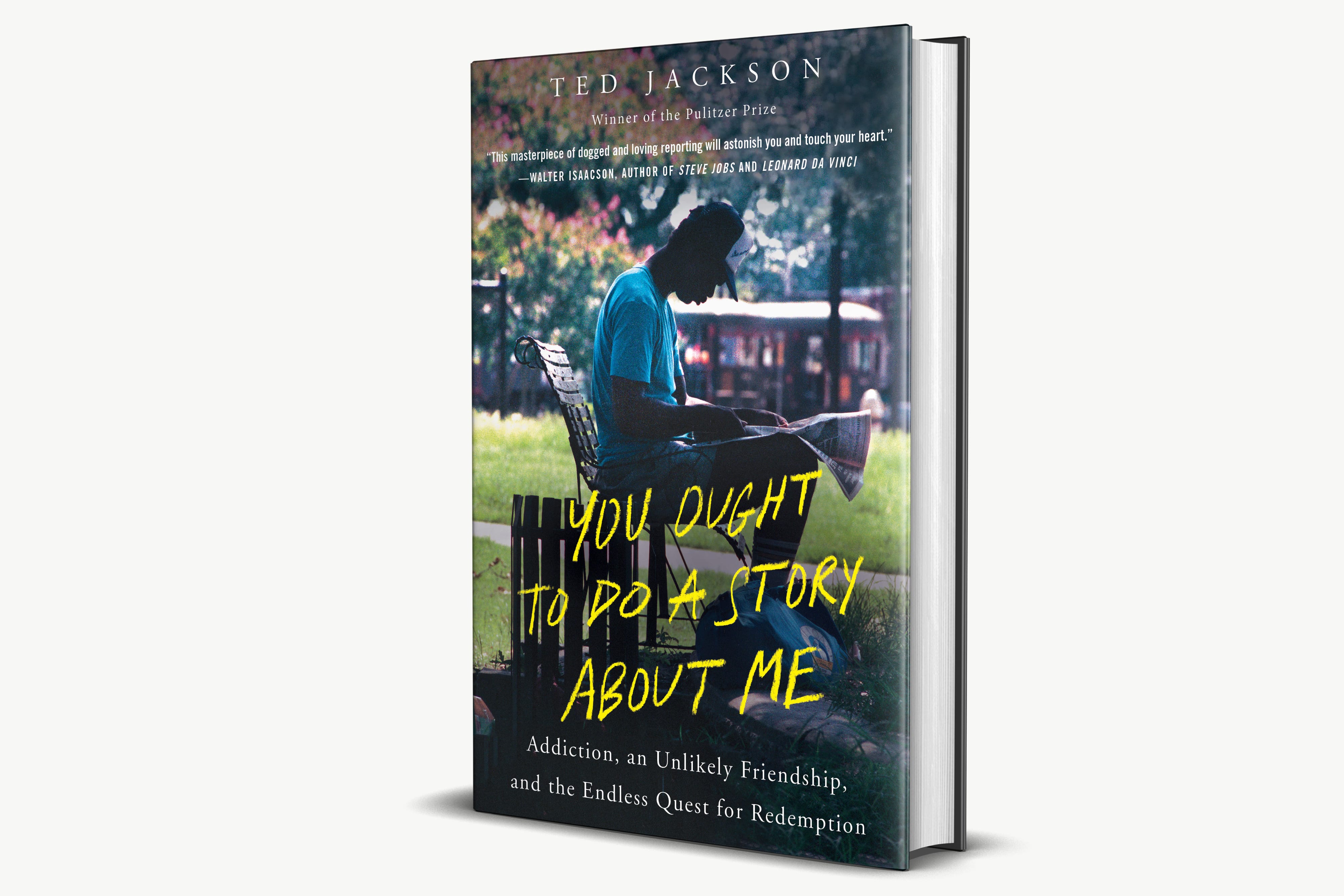

Thus begins “You Ought to Do a Story About Me,” Jackson’s biography/memoir of Wallace, a New Orleans native, St. Augustine High School football legend, and former NFL player who played in two Super Bowls. It is a gripping account of addiction, tragedy, friendship and redemption in a city that knows such things all too well. It is a cautionary tale and a modern-day parable, grounded in the deep faith both Jackson and Wallace share.

He set two well worn Nikon film cameras on the kitchen table of his Covington home where we met to discuss the book and his experiences as a photojournalist. The paint was worn thin on the focus rings and chipped in places on the camera bodies. In his thirty-three and a half years at The Times-Picayune, Jackson had seen a lot.

‘I thought it was like anybody else saying, ‘Shoot my picture…’

In 1990, on a tip from his editor, Kurt Mutchler, Jackson found himself beneath the overpass of the Pontchartrain Expressway, not far from where the Costco is now. He was looking for a homeless encampment, but by the time he got there, the site was destroyed and its inhabitants gone. Stepping gingerly over the detritus, Jackson was deflated. He was about to give up, when he encountered Wallace, sleeping on a rusty cardboard covered boxspring, and swaddled in a clear plastic “sheet.” He was asleep until Jackson shook him awake after making a few photos. His mind was clouded. But his surroundings were neat and orderly, belying the situation of a man addicted to crack cocaine. He looked intently at Jackson.

“You oughta do a story about me,” said Wallace.

Jackson was dubious.

“I thought it was like anybody else saying, ‘Hey man. Hey Mister. Shoot my picture. You know. Put me in the paper.’ That’s all I thought was happening at that time,” said Jackson.

View this post on Instagram

But when Wallace revealed that he was a former NFL player, the story began to take on a life of its own. In 1990 “The Times-Picayune” was running a series called “The Real Life: Surviving After the NFL,” and Wallace’s story became a sensation. It caught not only the imagination of the public but of his friends and family, especially his St. Augustine High School family. The outpouring of love was immediate and profound. It also caused the NFL to take a hard look at the lives of former players, who were previously discarded by the league much like Wallace was.

“When the story came out and he was whisked off the streets and taken to a Baltimore rehab, I thought that was the end of it,” said Jackson.

“I thought ‘Job well done that was a cool story. What’s next?’”

Two years later, Jackson was in the newsroom editing captions when he heard a knock on his window.

Photo by Ted Jackson

“I looked up and I see Jackie Wallace in a three-piece suit with a grin as wide as a mile, saying ‘Do you believe in miracles?’” said Jackson.

For miracles to happen, unbelievable circumstances must exist, and Jackson coming to New Orleans in the first place was one of those. A man of deep Christian faith, the gin-soaked Gomorrah on the Gulf was an unlikely landing place for the native of McComb, Mississippi.

“I thought I grew up in Mayberry,” Jackson quipped, “but I didn’t understand the currents that were flowing beneath my feet. Out of my sight.” The racism and inequality that plagued Wallace in the St. Bernard housing projects was another world to Jackson. As was the culture of New Orleans.

“Yeah it was very different and I never saw myself living here. Ever,” said Jackson. “And so when I came over to apply (at The Times-Picayune) I was thinking ‘I really don’t want this. This is not where I want to be. This is not where I want to raise my family.’”

The Times-Picayune offered Jackson the job, and his wife Nancy encouraged him to take it. Just as she encouraged the former graphic artist and sign painter to pursue a career in journalism despite having one young son and another on the way. It was an act of faith.

“We are hiring you to photograph chicken dinners on Sunday afternoon. Little old ladies at chicken dinners on Sunday afternoons. That was the quote,” Jackson recalled editor Charlie Ferguson telling him.

It wasn’t the high flying journalism that Jackson had hoped for, but by shooting these “picayune” assignments, Jackson developed empathy and humanity. This would prove useful in his first big story.

On the outside, looking in

“When I came to New Orleans, nothing I understood about race and poverty made sense anymore,” said Jackson. “And the turning point was when Kurt Mutchler called me in his office one day and said I want you to work on a story in Desire Housing Projects and I want you to disappear off the assignment logs for as long as you need.”

After six-weeks, he fell into depression, and couldn’t photograph the story any longer. The piece would go on to win the AP photo-series of the year, but Jackson wasn’t impressed with himself.

“It wasn’t the first time I had seen it, but it was the first time I had to wrestle with it,” said Jackson. I had to take what I thought was the reality of the bootstrap mentality, you know, ‘You guys can do it. Rah! Rah!’ And really tried to put myself in that place with my children.”

Lost and Found

Desire taught Jackson to look deeper, not simply into his subjects, but into his heart. Jackie Wallace taught him that stories are rarely neat and endings rarely predictable. By 2001, the miracle had ended. After eleven years of sobriety, Jackson discovered Wallace had slipped back into addiction.

“It was crushing,” Jackson recalled. “I had to wrestle with my ego a little bit. Because I couldn’t tell why I was so upset. Was it because I couldn’t stand there and say ‘Look at the power of photography and how it changed life.’ Well, it changed it for a while but it didn’t last. And so was it that? Or was I really crushed over Jackie’s fall? And it was both.”

Over the next 16 years, Jackson found and lost Wallace multiple times. He told Wallace that “he was writing the last chapter” of his life and the importance of a good ending. He understood how tenuous the situation was. But this was no longer about a good story. This was about an unlikely and enduring friendship. And Jackson understood the story was bigger than both of them.

In 2018 The Times-Picayune ran Jackson’s piece, “The Search for Jackie Wallace,” which became the most-viewed story in the history of the paper — and was written by a photographer. It resonated in a way that shocked both Jackson and Wallace and laid the groundwork for the book.

“Jackie and I both feel like we met each other for this purpose,” said Jackson. “That our entire careers pointed to that moment. And this was our purpose in life. And everything else just led up to it.”

As for Wallace? He is currently living at a drug rehab center, not as a patient, but as a mentor to “the younger guys coming through.” He is still a star in his own right. The son of uptown New Orleans who came of age in the St. Bernard projects, who broke tackles as a quarterback for St. Augustine High School, and made them up until his final stop with the LA Rams. Two hip replacements have slowed him considerably. The specter of Chronic Trauma Encephalopathy, or CTE, is a constant concern of the man known as “The Headhunter” during his NFL days. But Wallace is also grateful. As a man who tried to commit suicide twice, he realizes his story could have ended much differently.

“He’s thrilled with the book,” said Jackson. “His health is improving. His spirit and his eyes are bright and he’s so enthusiastic about his potential right now. And the book has given him a new life knowing he has a chance to speak to the world again.”

Ted Jackson is currently on a mostly virtual tour supporting the book. The book can be purchase through Amazon, and at local outlets such as Octavia Books.

This post was originally published in September 2020 and has been updated to include information about our show Only In New Orleans.