Joseph Jenkins never set out to be the counsel chief, the most senior member in his Mardi Gras Indians tribe, the Guardians of the Flame Maroon Society; in fact, Jenkins never expected to live past his 20s. In an interview with Queen Cherice Harrison-Nelson of the Guardians of the Flame Maroon Society, Jenkins said “You don’t just come out and say, ‘Well, I’m going to be a Counsel Chief.’ It don’t work that way. You got to obtain that experience. Then everybody looks at you as a special person, because of what you’ve been through.”

Jenkins died in hospice on April 16, 2020, at 90 years old from natural causes, but due to restrictions from the coronavirus pandemic, it was difficult to have his funeral right away. A U.S. Army veteran, Jenkins’ body was committed in the Southeast Louisiana Veterans Cemetery in Slidell on June 26th with only a handful of people in attendance. Many of Jenkins’ friends are older and have an increased risk of severe illness from coronavirus, therefore, it was difficult to arrange transportation or carpool to the Northshore.

Instead, a larger group at the state recommended level of 25 or less people, met on the Southshore and attended Jenkins’ homegoing on July 14, 2020, on what would have been Jenkins’ 91st birthday. The homegoing was held outdoors at the New Orleans Jazz Museum at the U.S. Mint and was arranged by Harrison-Nelson and Jerome Smith, a former Freedom Rider and director of the Treme Center.

Guardians of the Flame

Jenkins met Harrison-Nelson in his late fifties after he was wrongly convicted of criminal murder in 1957 and released after 30 years in prison. He joined the Guardians of the Flame, which was headed by her father, Big Chief Donald Harrison, Sr. When Harrison-Nelson started masking as an Indian, Jenkins became second chief. The two chiefs would design and sew their suits at the Harrison home for almost a year leading up to Fat Tuesday. One day, when the two chiefs were sewing in the family den, Harrison-Nelson went up to her father and asked, “’Daddy, can I do this? I want to be your Queen.” He told her no.

“I didn’t want to let my daddy know I was hurt,” she said. “So, I looked at Joe and said ‘Joe, can I mask with you?’ And he said, ‘Yes.’ Joe was always my chief. I was always his queen.”

Harrison-Nelson’s father was very intentional with the name “Guardians of the Flame.” She said her father meant, “We guard the flame, the flame of Africa that’s embedded within this tradition and we pass it on.”

When Chief Harrison became an ancestor, Joe took that role as the patriarch of the group very seriously. “He’d stoked the embers of the flame,” she said.

At her father’s funeral in 1998, then-Mayor Marc Morial said that Chief Harrison’s flame didn’t go out.

“I say that now about Joe, his flame was not extinguished, it just flickered and it’s going to burn in us and all of the people he had an opportunity to touch,” Harrison-Nelson said. “And it will burn brightly.”

Homegoing

A “homegoing” is oftentimes a jubilant celebration of the freedom after death, and is a tradition started by African enslaved people who were exposed to Christianity in America. The homegoing celebration at the old U.S. Mint began by celebrating Jenkins’ African roots. The Guardians’ Andrew Wiseman from the Ewe ethnic group of the African country of Ghana, poured water libations during a dirge, an expression of mourning.

The dirge was followed by the striking and shaking of tambourines as Big Chief Clarence Dalcour of the Creole Osceolas sang the traditional Mardi Gras Indians prayer:

“Madi cu defio, en dans dey, end dans day

Madi cu defio, en dans dey, end dans day

We are the Indians, Indians, Indians of the nation

The wild, wild creation

Oh, We won’t bow down (We won’t bow down)

Down on the ground, (On that dirty ground) . . .”

“My mother taught me that I was born Black and poor, but I will never, never be dirty,” said Smith as the homegoing continued. At age 80, former Freedom Rider Jerome Smith still has a commanding presence due in part to his height of 6’4”. He wore a patterned African kufi cap and a white protective mask because of COVID-19, and occasionally punctuated his words by tapping his carved African walking stick on the slate-covered ground in the French Quarter. Smith talked about working with Jenkins at the Hunter’s Field recreational area in the 7th Ward after Jenkins’ release from prison. Smith tapped his cane saying, “Love is an action word!”

Smith explained Jenkins’ action when Hunter’s Field had become infested with drugs and paraphernalia.

“Brother Joe cleared all that up by himself,” he recalled. Smith said that Jenkins embodied the spirit of good, of none surrender, of “no hum bow.” Smith first learned the phrase in Sunday school and then from Mardi Gras Indians during Carnival. In the distant past, rival tribes or gangs might occasionally clash or fight in the street and a “humbug” could occur, especially if a gang demanded another gang to bow down. Though similar to the phrase “we won’t bow down,” no hum bow is more about the individual’s spirit and not surrendering in the face of adversity.

The World Outside

While Jenkins faced adversity inside prison, the world outside changed. Jerome Smith joined the Freedom Riders in 1961, who felt empowered to test state and local laws after the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Boynton v. Virginia in 1960. The ruling held that racial segregation was forbidden in public transportation including bus terminals. On one bus ride, Smith was arrested in Jackson, Mississippi for violating segregationist Jim Crow laws by using whites-only facilities. Smith was engaging in #GoodTrouble as fellow Freedom Rider, U.S. Representative John Lewis, used to say before his passing on July 17, 2020.

“Joe didn’t become a hard-hearted man, he still had compassion.”

On another bus trip, Smith and other Freedom Riders were beaten by a racist mob in McComb, Mississippi. Smith endured near-fatal blows to his head with brass knuckles that left him with headaches to the present day. Barely conscious, he escaped by rolling into the back of an old truck operated by a Black farmer. Later that same week he got back on the same bus and continued the freedom ride to New Orleans. “I could not surrender my spirit. No hum bow,” he said.

The Mardi Gras Indians’ no hum bow spirit began in the late 1800s with tribes like the Creole Wild West headed by Chief Becate Batiste. Masking on the day of Mardi Gras afforded a rare opportunity for African-Americans to dance freely in the streets and almost in defiance of the segregated Jim Crow South. Smith recognized the power of this proud feeling and in 1969 he organized the first Mardi Gras Indians Super Sunday parades, which often ended at Hunter’s Field.

While Smith organized community centers and parades, Chief Jenkins was a quiet activist on a smaller scale. Smith was nicknamed “Big Duck” because he often had kids from Hunter’s Field or the Treme Center trailing behind him like little ducks. Chief Jenkins, on the hand, often spoke to the little ducks one on one.

“Joe didn’t become a hard-hearted man, he still had compassion. He loved children and was always trying to drop wisdom on you,” said Harrison-Nelson. “Jenkins stressed to the children that the inhumane actions of others shouldn’t affect your heart or erode your humanity and that you should always have love for your fellow human being.”

Working at the Treme Center, Jenkins would whisper in the ears of children to be strong, and not get caught up in the ills of a legal system designed to trap them and give longer sentences to people of African descent.

The Shooting on Mardi Gras

On Mardi Gras (March 5) 1957, 25-year-old Jenkins was walking on Canal Street with his tambourine when he bumped into a white 26-year-old Tulane student, August P.J. During. During was in a group of eight, all costumed as prisoners, with black and white stripes. Derogatory remarks were exchanged. According to witness Eugene Morse, a New Orleans fireman, During threw a beer bottle at Jenkins and “the white man had his fists rolled up walking toward the Black man (Jenkins).” Morse said Jenkins backed up about 15 feet from the group and pulled out a .32 caliber pistol he was carrying for protection and fired multiple warning shots. Undeterred with his fists raised, During continued to stalk towards Jenkins. Morse believed Jenkins was acting in self-defense when he fatally shot During twice in the chest. Police officers investigating the scene took a statement from Morse but never followed-up. Morse learned of Jenkins’ trial and showed up to testify, but was told he wasn’t on the witness list by a clerk so he left the courthouse.

Jenkins wanted to argue self-defense in court, which meant the killing was not criminal and instead a justifiable homicide. But Jenkins’ defense team decided not to argue self-defense as they had no knowledge of Morse’s statement to NOPD. At the trial, an all-white jury convicted Jenkins of murder and then sentenced him to death.

When Jenkins was convicted of killing a white Tulane student in 1957, it was six years before Tulane even allowed Black students. Jenkins was in prison before the Freedom Rides, before the March on Washington, and before six-year-old Ruby Bridges and the McDonogh Three integrated New Orleans schools while being escorted by Federal Marshals.

Life and Near Death in Solitary

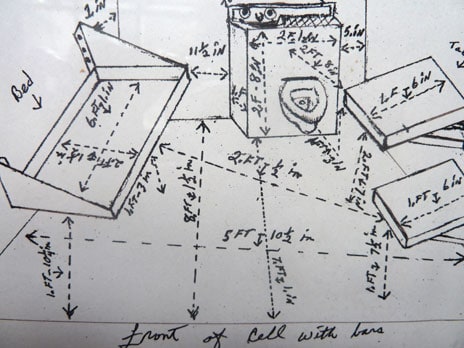

When escorted to prison, Jenkins spent 15 years mostly at Angola, the Louisiana State Penitentiary, and mostly in solitary confinement on death row. He had four dates with the electric chair, twice coming within hours of execution. Death row inmates lived in a windowless 6 by 9-foot cell. Every three days inmates were allowed 30 minutes outside the cell to shave, shower and walk in the windowed hallway, but they weren’t allowed outside the building. Loyola law professor William Quigley wrote, “Evidence in federal litigation in 2014, found temperatures were consistently over one hundred degrees in cells on Death Row at Angola, sometimes with a heat index of 107 degrees.”

A 2019 medical study showed that prisoners in solitary are 31% more likely to develop high blood pressure than less-isolated prisoners, and those in solitary were more likely to have strokes or heart attacks as a side effect of hypertension. Jenkins had two heart attacks while in prison.

In 1972, the United States Supreme Court suspended all death penalty cases with the Furman v. Georgia case, and Jenkins’ death sentence was later changed to life imprisonment. At the time, African-Americans received a disproportionate amount of death sentences. Justice Potter Stewart wrote “I simply . . . cannot tolerate the infliction of a sentence of death under legal systems that permit this unique penalty to be so wantonly and so freakishly imposed.”

After additional rulings, Louisiana amended its laws and began using first, second, and third degrees for murder. Under the current statutes, Jenkins’ case would likely not have qualified for first-degree murder and the corresponding the death penalty.

Angola: Plantation to Prison

Though no longer on death row, Jenkins was still in Angola, which at times has been called “America’s Worst Prison” and the “Bloodiest Prison in the South.”

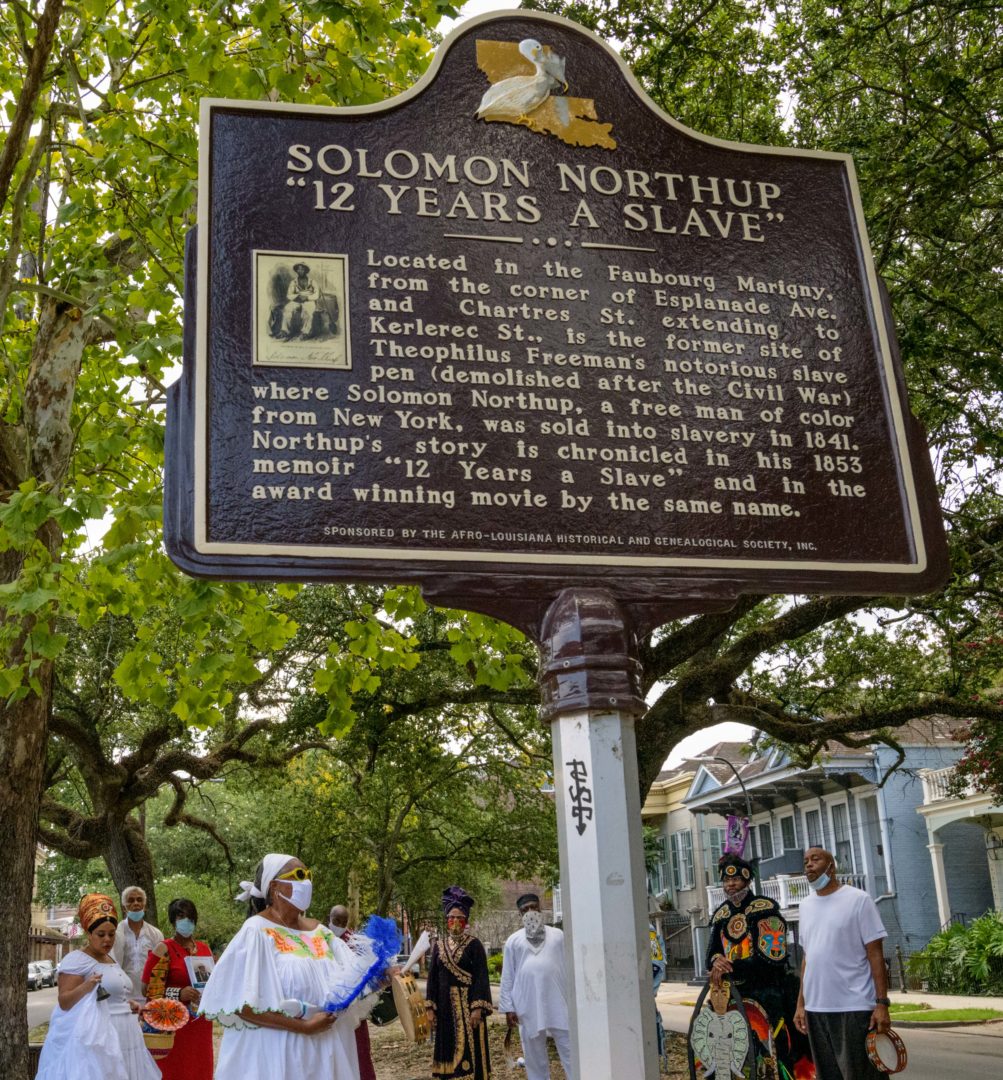

Before it was a prison, it was a slave plantation where many of the slaves came from the African country of Angola. The Angola plantation was only 30 miles from the plantations where Solomon Northrup was forced into labor and came close to death as detailed in his memoir “12 Years A Slave.” After the Civil War, the lease of the state penitentiary was given to a former Confederate major, S.L. James, in 1870. James leased out prisoners as slave labor to surrounding plantations. He purchased the Angola plantation in 1880 and many Black convicts lived in former slave quarters. James was called “the largest slaveholder of post-bellum Louisiana.”

Even after the practice of leasing out prisoners ended in 1901, Black prisoners still made up a disproportionate percentage of Angola’s population. According to the Vera Institute of Justice, the Black incarceration rate in prisons in Louisiana has increased 201% since 1978. In 2017, Black people were incarcerated at 3.6 times the rate of white people, and Blacks represent 67% of prisoners in the state’s prison system, despite only representing 33% of the state’s total population.

Medieval, Squalid and Horrifying

In 1951, shortly before Jenkins’ arrival, over thirty prisoners at Angola slashed their Achilles tendons in protest of forced labor and other brutalities. The macabre “Heal String Boogie Incident,” was named after a song the prisoners allegedly sang while slicing their tendons with razor blades. Reform hearings called after the incident included testimony from nurse Mary Margaret Daughtry. Daughtry called the prison a “sewer of degradation.” Daughtry testified that the brutality had always existed, “and always will as long as the penitentiary is used for a political football and dumping grounds for the state of Louisiana.”

For much of its history, the prison employed few guards and instead let many of the “trusty prisoners” have guard duties. The trusty system continued into the 1970s with often disastrous results including many assaults, stabbings, and rapes. In 1971, lawyers with the American Bar Association inspected Angola and described the conditions as “medieval, squalid and horrifying.”

Harrison-Nelson recounted conversations with Jenkins about his time in prison.

“He told me some of the horrible things that happened to him, but I know he didn’t tell it all,” she said. “He told me what he knew I could stomach.” But over time Jenkins revealed how guards shouted racist epithets at him, spit on and beat him including kicking his genitals. “He told me how his mother cried for him, and how she did not get to see him become a free man.”

Justice Delayed

Decades later Eugene Morse still wanted to be heard by the Orleans Parish District Attorney. Eventually, he gave up and contacted WWL-TV in 1986. A long segment aired where Morse and other witnesses questioned Jenkins’ conviction. After the story aired, Jenkins’ life sentence was commuted to 80 years making him eligible for parole. He was paroled in 1987, after nearly 30 years inside. Morse was finally allowed to testify before a judge on April 26, 1991; 34 years, 1 month, and 21 days after Mardi Gras 1957.

With Morse’s testimony, Jenkins was granted a new trial where the defense moved to quash the original indictment with a motion that read “The composition of the grand jury which returned the indictment is unconstitutional by present standards in that Blacks and women were systematically excluded from service on the grand jury.” The court agreed to quash the indictment on Oct 10, 1991 making Jenkins finally free. He no longer had to worry about the remaining 46 years of his parole.

Jenkins later sued the City of New Orleans in civil court and was initially awarded $12.6 million in damages for malicious prosecution. His attorneys argued that the NOPD and the DA purposely kept the statements by Morse and other witnesses from the defense.

While Jenkins was in prison the U.S. Supreme Court heard the case of Brady v. Maryland in 1963 where testimony was withheld by the prosecution that could have lessened Brady’s punishment. The Brady ruling established that the prosecution must turn over all evidence that might exonerate or lessen the punishment of the defendant.

But Jenkins’ civil judgment was later reversed when the City of New Orleans went to the Louisiana 4th Circuit Court of Appeals. The opinion of the appeals court stated that “[Brady v. Maryland], rendered in 1963, was not in effect at the time of Jenkins’ [1957] criminal trial and does not apply.”

I’ll Fly Away

Despite having 30 years of his life taken from him by the ills of the justice system, Harrison-Nelson said Jenkins exuded love. As she spoke at the homegoing, she wore a protective mask decorated with silver and gold rhinestones that spelled out ‘LOVE’.

The homegoing at the Mint continued with dirges, drumming, and dancing from the Guardians and other tribes like Cheveyo and the Golden Blades. Voodoo Queen Kalindah Laveaux of the Seven Sisters sang “I’ll Fly Away,” which was followed by a dove release by Big Chief Dalcour. The dove is a symbol of peace, hope, and freedom; and in a memorial, it can symbolize letting a loved one fly away.

Wearing masks and keeping a social distance, the mourners paraded a short distance through the French Quarter to a nearby historical marker where Solomon Northup was sold into slavery in New Orleans in 1841, beginning his time as “Twelve Years A Slave.” Guardians Ambassador Queen Jamilah Y. Peters-Muhammad spoke underneath the marker while holding a tambourine and a large blue-dyed ostrich feather from a Mardi Gras Indian suit. She spoke of the similarities of Solomon Northrup’s torture not far from the Angola plantation and Jenkins’ thirty tortuous years in Angola prison. Close by, Harrison-Nelson began to weep as she recalled Jenkins’ tales of torment.

“Joe taught us the message of not looking for revenge. “

Peters-Muhammad continued to draw lines connecting the past into the present. She paraphrased a statement by Kimberly Jones, who protested the killing of George Floyd in May, “Americans should be glad that we want equity and not revenge.”

Bouncing the feather and jingling the tambourine to punctuate her speech, Peters-Muhammad continued, “Joe taught us the message of not looking for revenge. He could have been a hateful man; he had every reason to be a hateful man, but instead, he chose love. So, as we move forward choose love, choose love, choose love!”