Did you know mankind is heading back to the moon for the first time in the 21st century? This is no pipe dream. There’s a plan in place and it’s happening sooner than many may think.

But we’re not stopping at the moon this time. This time we’re going all the way to Mars, marking the first time manned vessels travel into deeper into space.

This is huge news for every inhabitant of Earth (and *gulp* elsewhere?).

These missions can change the trajectory of human history, but these missions have their beginnings locally — here in New Orleans.

Robert Champion is the director of NASA’s Michoud Assembly Facility in New Orleans East.

“People call it ‘NASA’s rocket factory,’” he explained. “The history and future of space exploration goes through Michoud. It goes through New Orleans.”

It’s easy to dismiss this kind of talk as grandiose, but it’s not. Every mission — and advance in American space exploration — over the last 60 years involved the work of New Orleanians.

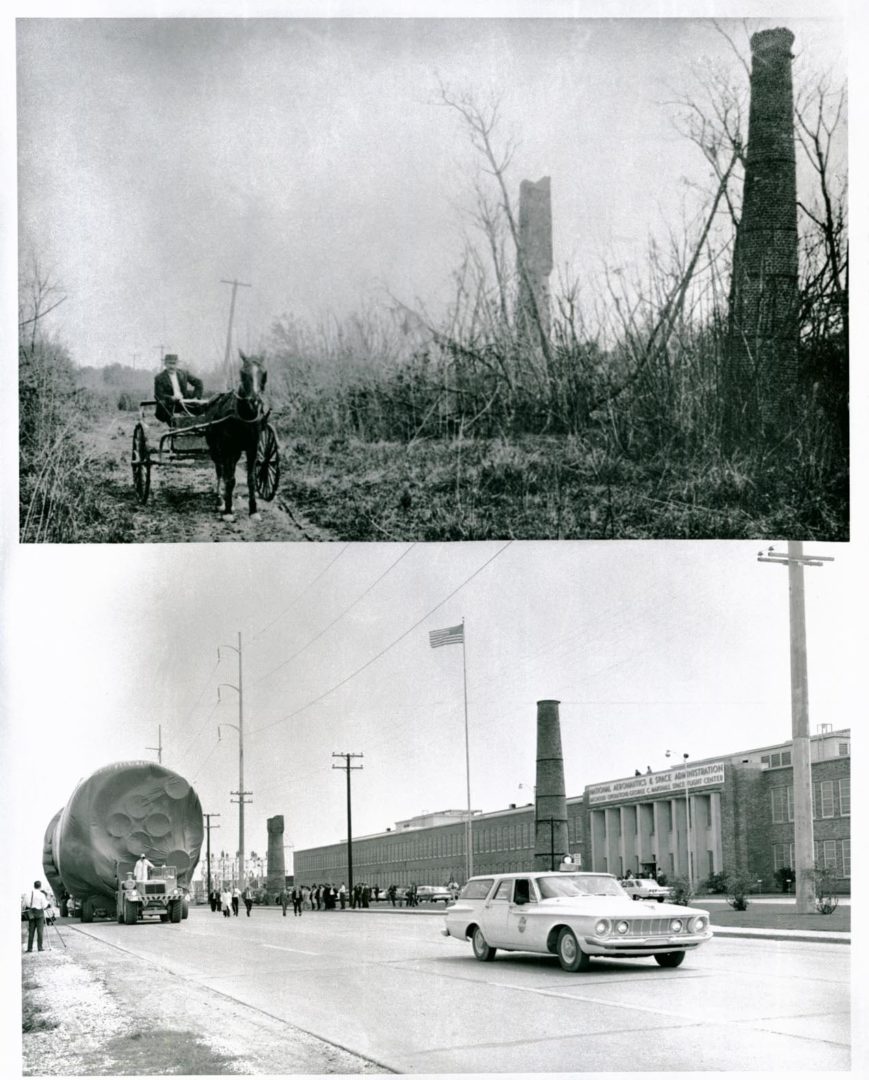

Swampy History

The history of the land on which the Michoud Assembly Facility sits can be traced to March 10, 1763 ,when Louis XV, king of France, granted a 34,500-acre swampy, cypress tree-filled tract to French soldier and New Orleans merchant, Gilbert Antoine de St. Maxent.

The land had several owners over the next five decades, including the Clouet family of “Clouet Street” fame. In 1827, Antoine Michoud — a highly educated and cultured artist who left France after the fall of Napoleon and created an arts shop on Royal Street — purchased the property and operated a sugar plantation on it. He lived until 1862 and passed the property to his nephew, Jean Baptiste Michoud, who lived in France and never saw his new home.

Jean Baptiste sold one plot of the land to what would become the Louisville & Nashville Railroad, and another to the U.S. government for a lighthouse. This would be the first — but most definitely not the last — time the federal government owned at least a portion of the Michoud tract.

The property remained with the Michouds until it was sold again in 1910. By then, the drainage technology allowed New Orleans to remove swampland and open previously untouched areas of the city for development, resulting in new neighborhoods sprouting all over the city. Developers saw a similar opportunity at Michoud Plantation, but bad business and litigation halted those attempts.

Instead, the first half of the 20th century saw the land used for telephone and telegraph lines, lumber, muskrat hunting, and a section of the federal government’s Intercoastal Canal.

The trajectory of the property changed dramatically in 1941, when the United States entered World War II. As America prepared for war, the government set the Michoud land — with vast space and easy access to the Intercoastal Canal — aside for an additional canal, and for sea- and aircraft to be built by Higgins Industries — the company that built the famed Higgins Boats that were featured in the Allied invasion of Normandy on D-Day.

A shortage of steel and wood — as well as the time-intensive landfill that Michoud swamps required — resulted in the cancellation of the Liberty Ship and cargo plane programs, leaving the property with the task of creating C-46 wing panels that would be assembled in Louisville and St. Louis.

But the land was now in government hands and housed millions of square feet of manufacturing and office space. When the Korean War broke out, the Michoud facility was ready to be put to work. From 1951 to 1954, the Chrysler Corporation was awarded a contract to build Patton and Sherman tanks, and with the help of 2,200 New Orleanians — all built in Michoud.

When this work was done, the facility became dormant. But the dormant space was still costing the government tons of money to maintain. The problem was solved in 1961, when Dr. Wernher von Braun — the first director of a young, but growing governmental agency, called the National Aeronautics and Space Administration, or NASA, took an interest in the facility.

‘We Choose to Go to the Moon’

On Sept. 12, 1962, at Rice Stadium in Houston, President John F. Kennedy told the crowd, “We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard; because that goal will serve to organize and measure the best of our energies and skills, because that challenge is one that we are willing to accept, one we are unwilling to postpone, and one we intend to win, and the others, too.”

It’s easy to forget that when Kennedy made this speech, the United States was far — very far — behind the Soviet Union in the space race. The Soviets had launched the first satellite, Sputnik, into orbit around the Earth five years earlier and had sent the first man into space in 1961.

But Kennedy’s words rallied America and set the nation on a course of unparalleled scientific achievement with an estimated 400,000 Americans working on various components of the Apollo program.

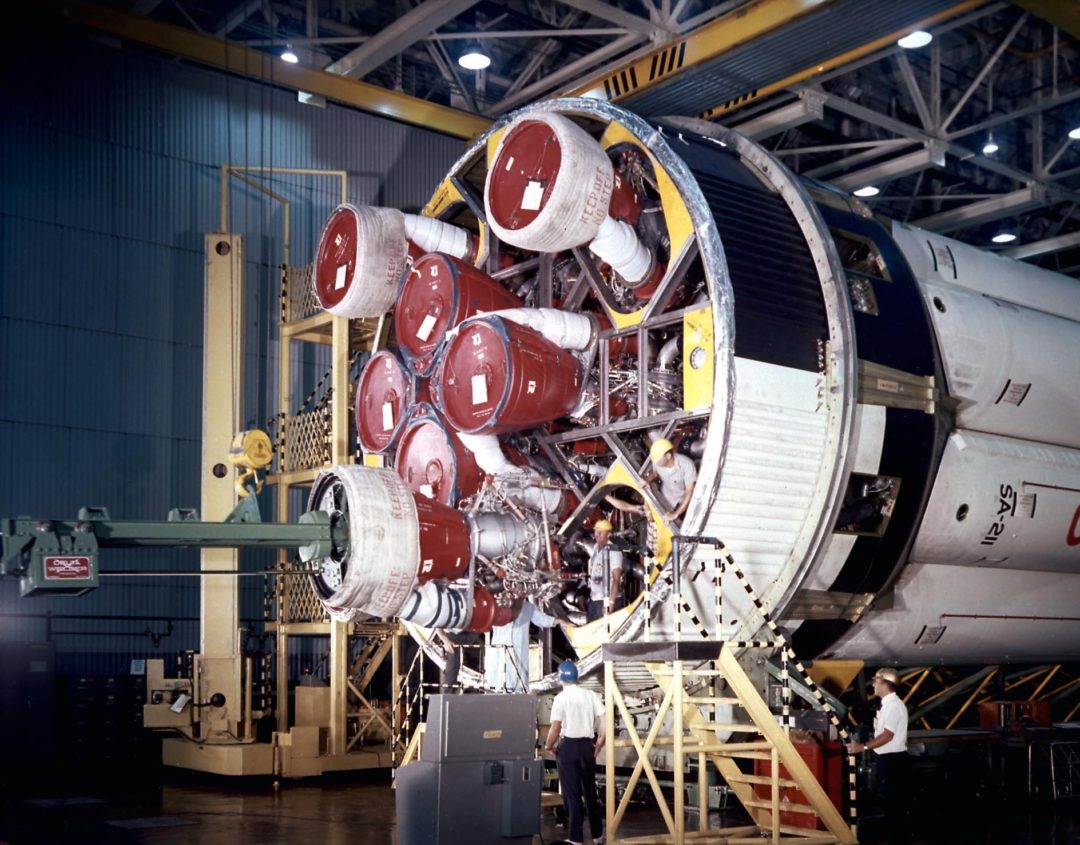

One of the big challenges to overcome was where the massive Saturn rockets — chosen to launch the manned spacecraft from Earth — would be manufactured. The Saturn V rocket is the Saturn iteration that took the astronauts of Apollo 11 to the Moon’s surface, and that rocket (plus the spacecraft) was 363 feet tall. That size — and the frequency in which rockets needed to be created — required the involvement of several facilities in the rocket’s construction.

A Saturn rocket’s launch takes place in three stages. The first stage — the tallest section of the rocket — was built at the Michoud Assembly Facility. It’s incredible to think that the equipment involved in the initial launch of every Apollo mission — manned and otherwise — was constructed by a team of New Orleanians. The first two minutes and 42 seconds of flight, including a liftoff producing 7.5 million pounds of thrust, was primarily the hard work of the people in this city.

The large space available in the Michoud Assembly Facility — room for 31 football fields — made it the ideal place to construct the first stage of the Saturn rockets. From there, the completed component would be placed on a barge and shipped via the Intracoastal Waterway to the Kennedy Space Center in Florida, where it would rendezvous with the other stages and assembled for eventual liftoff.

Generations later, Champion puts this work into perspective: “Without the proven expertise and abilities of NASA’s workforce at Michoud, man would not have landed on the Moon. It’s that simple.”

And Beyond

The Apollo program concluded in 1975, but that doesn’t mean New Orleans’ role in space exploration ended. From 1981 to 2011, NASA’s focus was on the Space Shuttle program, calling for spacecraft to be partially reused after completing missions to low Earth orbit.

“Not only did the program send 135 missions into space over those 30 years, but it served as a lab conducting important experiments allowing us to advance to where we are today,”Champion explained. “And, in those three decades, Michoud was creating large components for the International Space Station, as well as all 135 of the shuttle external tanks: the largest and heaviest component of the Space Shuttle.

Today, NASA has taken on its most ambitious project yet. It’s called Artemis — named after the Greek goddess of the moon, and the twin sister of Apollo.

But this is no Apollo replica.

The program has already begun as NASA assigned specific private companies the task of transporting equipment to the lunar surface for scientific exploration and to prepare the moon’s South Pole (where water was discovered) for sustained human presence. Artemis I is planned for next year, when NASA’s new rocket — called the Space Launch System (SLS) and the most powerful rocket in the history of spaceflight — will lift off, carrying the Orion Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle, the program’s new spacecraft. This mission will be unmanned and will send Orion into a 10-day orbit around the moon before returning to Earth. The SLS rocket and Orion spacecraft will be used throughout all of Artemis.

“SLS and Orion are part of the backbone for deep space exploration,”Champion said, “and we’re building major components of each inside Michoud.”

The largest piece of the 320-foot SLS rocket — the 212-foot long component known as the Core Stage — is being built in New Orleans, and not only holds the fuel required to launch a rocket with 8.4 million pounds of thrust, but also houses the rocket’s flight computers and most of its avionics, or the brain, which control the rocket.

The crew module pressure vessel — the section of Orion that will carry astronauts safely through space — is being built at Michoud, too, with one vessel already complete. The facility is also responsible for creating the launch abort system, which can propel the crew module from danger in milliseconds should something go wrong.

“To build these massive and important components, you need a massive facility, a highly trained local workforce, and a deep water port that allows NASA’s enlarged barge, Pegasus, to transport space hardware,” Champion explained. “Michoud is specifically suited to do this work well.”

In 2022, Artemis II will once again launch SLS and Orion, this time carrying four astronauts within 5,500 feet of the moon’s surface. That year and the next, the Lunar Gateway will be placed in moon’s orbit, serving as a science laboratory and a docking station for future Artemis missions to the lunar surface and beyond.

Artemis III will dock at that Gateway in 2024 before landing on the South Pole of the moon for 10 days. This will be the longest stay on the moon in human history, the first time a woman has landed on the moon, and the return of humans to the lunar surface after a half-century absence. And, most importantly, it will set the stage for the creation of a base at the moon’s South Pole to facilitate a sustainable human presence there by 2028.

Then, in the 2030s, the plan is for that same SLS and Orion — in large part constructed in our city of New Orleans — to take the first humans to the surface of Mars.

“It wouldn’t be possible without the work of our contracting partners and the employees of the Michoud Assembly Facility,” Champion insists.

But achievements are nothing new to this plot of land that once housed the Michoud Plantation. It’s through here that some of the region’s first railways ran. It’s here that new weapons of war were assembled. It’s here where the rocket that sent the first men to the moon was created, where our knowledge of outer space was enabled, and — now — as we look past the moon to Mars and beyond, where the trajectory of mankind will be altered.

[Arrange a free tour of the Michoud Assembly Facility by going here!]

A piece of music written to celebrate man’s arrival on the moon 50 years ago included the following words: “In the white light of Artemis, from the lonely mirror of her face, man looked down upon the blue splendor of the Earth, and for the first time he saw his home.”

It turns out the journey is just beginning, and we New Orleanians can be very proud of the role our home continues to play.

References

WRITER MATT HAINES LIVES IN NEW ORLEANS. FOLLOW HIM TO THE MOON AND BEYOND AT MATTHAINESWRITES.COM, AND ON FACEBOOK, INSTAGRAM AND TWITTER.