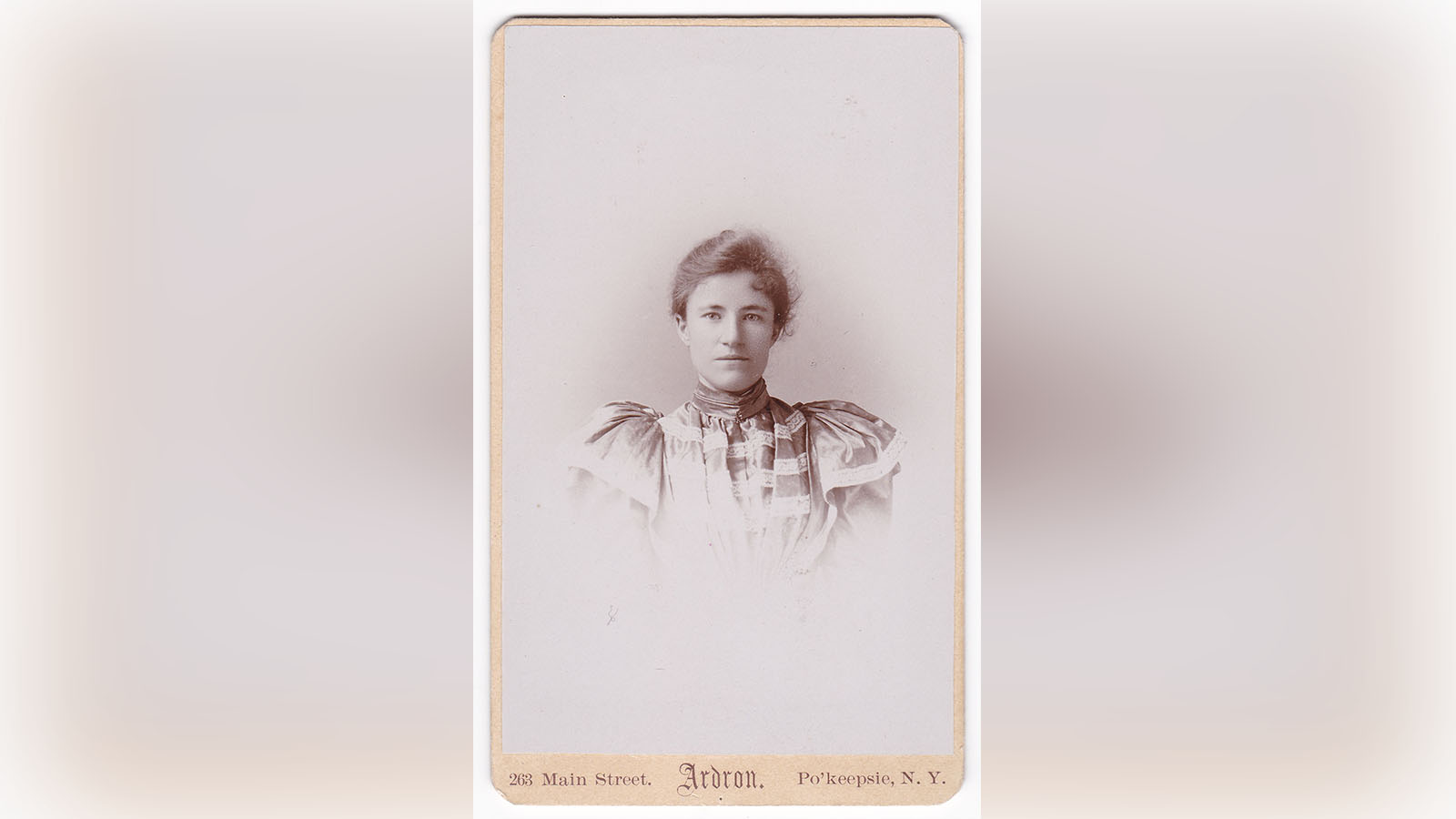

Cover photo courtesy German Roentgen Museum, Remscheid.

Marcella Imelda O’Grady was born in Boston to an Irish family in 1863. Unlike her sister, instead of becoming a nun after finishing high school, Boveri pursued a degree from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). She graduated from MIT with a concentration in biology in 1885, the first woman to do so. Although such a feat is much more common today, at the time, a woman, let alone a Catholic woman, pursuing science was a rarity.

After completing her studies at MIT, she was a science teacher for two years at the all-girls preparatory institution in Baltimore, the Bryn Mawr School. While teaching there, she applied for the Fellowship in Biology at Bryn Mawr College. She was accepted into the Ph.D. program running from 1887 to 1889, where she had the opportunity to dive into her areas of interest: embryology and comparative zoology. Her doctoral program would include a special research project involving fish embryology, which she pursued at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, Massachusetts.

When a professor resigned from Vassar College in 1889, Boveri postponed her Ph.D., opting to teach biology at the all-women’s college instead. By 1893, she was the department head of the biology program at Vassar.

A Sabbatical in Germany that changed her life

From 1896 to 1897, O’Grady went on sabbatical to Würzburg, Germany, where she would conduct research under the most prominent European cytologist of the time, Theodore Boveri. She was the first woman to be admitted to the science department at the University of Würzburg. Boveri was the director of the Zoological-Zootomical Institute in the German city.

The German cytologist wasn’t an advocate for women pursuing higher education by any means, and was initially upset by the university’s decision to admit Boveri. Since she was the only woman in the pool of male doctoral candidates and established scientists in the Würzburg research program, Theodore Boveri believed it be best for her to live in her own, private quarters, as opposed to boarding with the others.

To observe their progress, Boveri was responsible for conducting daily check-ins on the student researchers. At first, he made sure to leave Boveri’s door wide open when he did so. In a matter of months, Boveri’s door would be closed for long periods of time, with none other than her inside. An 1897 letter penned by Theordore and addressed to his sister-in-law reads, ‘I now have an American lady zoologist in the institute. I enjoy her company and must sometimes restrain myself.’ Marcella Imelda O’Grady would soon be Marcella O’Grady Boveri. They wed in October 1897.

Between 1901 and 1902, Marcella and Theodore Boveri tested his hypothesis, in which he reasoned chromosomes differed qualitatively. To test Boveri’s hypothesis, they artificially fertilized sea urchin eggs and analyzed the offspring’s embryos and larvae. From their findings, Theodore Boveri theorized a definite combination of chromosomes is essential to normal development, thereby going against the then widely held stance that normal development necessitates a definite number of chromosomes. Until 1902, each chromosome was thought to carry the totality of hereditary material, but their sea urchin egg experiments demonstrated that each chromosome is genetically unique.

The sea urchin egg experiments inspired Theodore Boveri’s chromosome theory of cancer; in which he raised the possibility that malignant tumors result from a certain abnormal condition of the chromosomes, one which is inherited through the division of cells. In his monogram, Zur Frage der Entstehung maligner Tumoren published in 1914, in English, The Origins of Malignant Tumors, he theorizes ‘The problem of tumors is a cellular problem [and] typically every tumor arises from a single cell.’ This single cell “contains, as a result of an abnormal process, a definite and wrongly combined chromosome-complex,’ [which] is passed on to all descendants of the’ single cell the tumor originated from.

Theodore Boveri died in 1915 due to complications of tuberculosis. As a newly single parent raising a 15-year-old daughter through World War I, Boveri was thrown into an even greater deal of responsibility. Surrounded by chaos and trying to emotionally recover from her husband’s death, it was difficult to conduct research as she had done so in the past. Boveri turned to other pursuits. She created a makeshift hospital in her Würzburg home for wounded soldiers. Theodore Boveri was a highly skilled pianist, and his love for music must have rubbed off on Marcella, as she organized Beethoven and Mozart festivals in Würzburg. Her daughter, Margret, would persevere through the War in her teens, eventually earning a doctorate and becoming a highly regarded journalist. In 1926, Boveri visited the United States, intending to stay temporarily. Her remaining family and colleagues would convince her otherwise. She would remain long term, beginning the next chapter of her life in Connecticut.

Albertus Magnus College was founded in 1925 in New Haven, Connecticut. The provost reached out to Boveri during the college’s initial expansion, asking her to join them as the department head of the biology program. There wasn’t a biology department at the time, so she would also be the founder. Yale University was eager to support Boveri in New Haven. Although not a professor at the university, Yale offered her unrestricted access to their Osborn Zoological Laboratory and libraries. Through Albertus Magnus College, Boveri had the freedom to further conduct research at the marine laboratory in Naples and the University of Freiburg in Germany.

The impact of Marcella O’Grady Boveri

Without Marcella’s thorough English translation of her husband’s, The Origins of Malignant Tumors, Theodore’s work may not have reached a wider audience outside of Germany. In the years preceding its publication in 1914, the monogram wasn’t receiving much attention. When it was first published there was great uncertainty and skepticism regarding the correct chromosome quantity for normal development and chromosome involvement in a person’s sexual orientation. Marcella’s 1929 English translation would make her husband’s theory of cancer more accessible across the world, surely sparking further developments in the field.

Although Theodore Boveri designed the sea urchin experiments, Marcella shared an equal role in their execution and the analysis of their findings. Despite her heavy involvement, Theodore omitted Marcella’s name from his original German monogram. Marcella followed suit in the English translation, so she never received formal credit for her contributions.

In addition to her involvement in her husband’s research, Marcella advanced numerous female scientists’ careers by submitting recommendations on their behalf for enrollment to graduate and doctoral programs in Europe, where she was connected with an intricate network of scientists. Vassar and Albertus Magnus Colleges were women’s colleges, which must not have been a coincidence. The supportive atmosphere at these institutions gave her the opportunities she deserved, and further allowed her the chance to promote other women in the field. And with that, it is appropriate to make the following clear: Marcella O’Grady Boveri managed to successfully pursue her passion for science despite the world, and the field as a whole, being dominated by the male population. For that, anybody can learn from her story, especially young girls and women with a dream.

References:

McKusick V. A. (1985). Marcella O’Grady Boveri (1865-1950) and the chromosome theory of cancer. Journal of medical genetics, 22(6), 431–440. https://doi.org/10.1136/jmg.22.6.431

Wright, M. R. (1997). Marcella O’Grady Boveri (1863-1950): Her Three Careers in Biology. Isis, 88(4), 627–652. http://www.jstor.org/stable/237830