There’s something extraordinary about being in the presence of a master, and even more so about being in their place of work. It can be easy to miss the storefront of local luthier Salvador Giardina at 101 Focis Street, right on the bend of the shopping center in Old Metairie. There are no sequined hot pants or neon lights in the window to catch the attention of passersby, as there are at the neighboring shops. Like something from the Wizarding World, it’s as if a person might only notice the shadowy doorway and peeling gold and silver letters on the glass if they’ve specifically come looking for them.

Hogwarts for Strings

The magic doesn’t end at the threshold, either. Each time I enter Stringed Instruments Restoration & Making (the official, somewhat unwieldy name of the shop) I’m reminded of Ollivander’s wand shop in the Harry Potter universe. The bits of wood and sawdust strewn about, the cache of familiar merchandise and unfamiliar tools, the distinct feeling of having been transported to another time and place. One could almost be forgiven for wondering if the bunches of horsehair hanging on the wall, which will eventually be stretched across bows, aren’t actually unicorn hairs to be inserted into the cores of select wands.

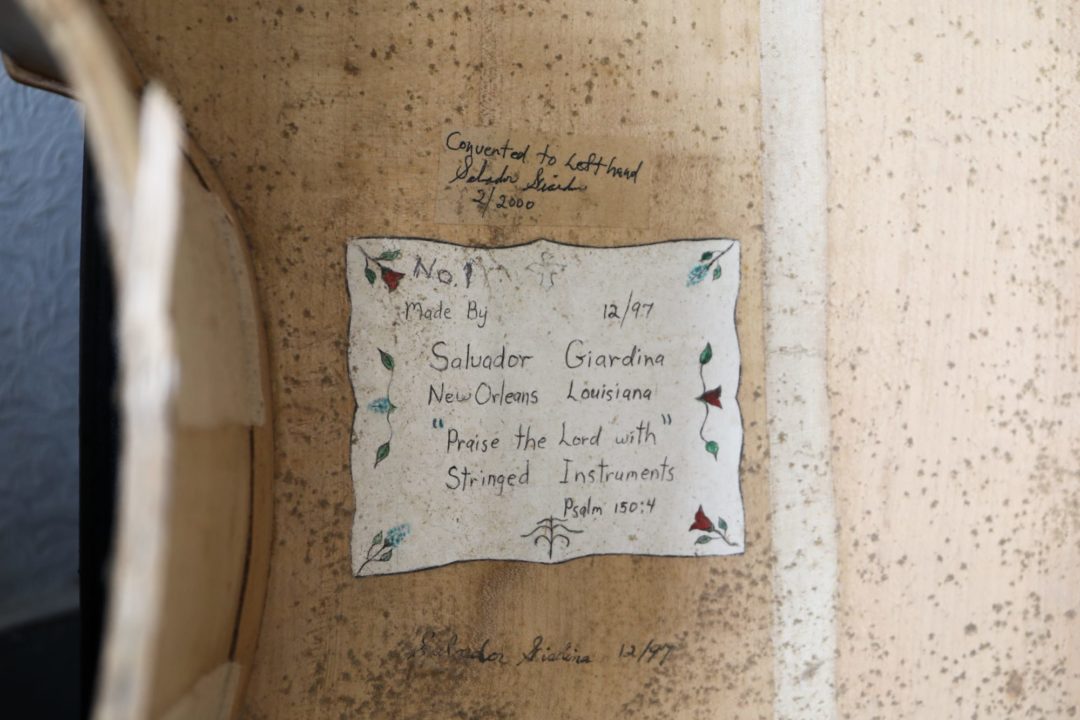

Of course, there aren’t wands lining the walls, but instruments. There are dozens of guitars of different sizes and in different states of repair or disrepair, a row of mandolins, some ornately painted dulcimers. In the corner are three enormous upright basses, and Sal informs me the first bass he ever made is the palomino-colored one at the back. He brings it forward and I can’t contain my gasp as he knocks the front of it clean off— it feels as if I’m bearing witness to some strange surgery. There inside is his tag: No. 1. 12/97. Made By: Salvador Giardina. New Orleans, Louisiana. “Praise the Lord with Stringed Instruments,” Psalm 150:4

“I built it for a right-handed customer originally, then converted it to a left-handed bass for the next customer,” he tells me (as corroborated by a handwritten note above the tag). Some years ago a friend happened upon it in a pawn shop, slightly worse for the wear. Sal can’t believe his luck in having the instrument find its way back to him, and he looks forward to getting around to restoring it.

“I always knew it was a mistake to convert it to a left-handed bass,” he muses, a bit irritated with his younger self.

The Masters

Though Sal identifies strongly with his own Italian/Sicilian heritage (“We say we’re Italian, but we’re really Sicilian,” he quipped at one point), and with the Italian tradition of instrument-making he carries on, he was actually trained by the German master Manfred Trautmann. A teenage Sal in need of repairs on his electric bass was referred to Trautmann’s shop on Magazine Street sometime in the ‘60s, and from the sounds of it, he scarcely left the shop in the course of the next decade.

“For the first three years, he just made me watch him. He used to say, ‘Giardina! You can learn just as much from watching as from doing.’ And that was fine. I loved to watch him. And then I had my official apprenticeship with him. We became very close. I used to drive him crazy… he’d always shout at me for leaving tools around and stuff like that,” he says with a laugh.

Sal is still in possession of some of those very tools— he shows me two of his favorite knives, and says the steel pot in which he melts his hide glue and the workbench itself were Trautmann’s as well.

On the counter is Sal’s current project: a violin. Impossibly thin strips of what I learn to be maple are loosely glued around a wooden mold.

“I get my wood from Europe, from the same trees Strad would have used in his.”

He’s referring, of course, to the 17th century Italian master Antonio Stradivari, whose work is widely considered to be the gold standard of luthiership.

“The wood’s really important,” he said. “It’s important that it have as little sap in it as possible, so they use high-altitude trees that they fell in the winter, when the sap’s all down in the bottom of the tree. In the old days they used to send the wood down the river and the water would help draw some of the sap out too. I don’t know if they do that anymore.”

I’m surprised to learn that this is the very first violin Sal will have made. “I’ve restored hundreds of them. I’ve been doing this for 45 years! But I never really had any interest in making one. I liked making cellos and basses. They don’t have all these tight curves.” He rattles off some prominent guitarists and bassists whose instruments he’s made– Steve Masakowski, Mark Whitfield, Roland Guerin. He’s particularly proud of the custom seven-string bass he built for Masakowski.

He also offers another, unexpected, reason for his hesitancy to extend his skillset to violins: “Strad was making violins until he was 93. I got to hold a violin he made when he was 93— a soloist with the LPO played one and she made me go look at it in the sunlight. It was like it was glowing from within. It was such a masterpiece, and I kept thinking, ‘He made that when he was 93 and I’ll never make anything that good!’ So I honestly didn’t even want to bother!”

‘People needed their music…’

However, he tells me the pandemic has given him the time and headspace to finally pursue projects such as this one. “I got to take a breath,” he says. I can tell that he genuinely appreciates having been able to take that moment of rest, but that it’s also a silver lining in an otherwise precarious time. I notice a framed Times-Picayune article on the wall about the “flood of damaged instruments” that came through Stringed Instruments Restoration in the wake of Katrina, and remark that the past six months have been an entirely different kind of catastrophe for musicians in New Orleans and, in turn, for him.

“Yeah, music was like the one thing that didn’t go away after Katrina,” he said. “Maybe it did for the first couple weeks, but people needed their music after that. And then yeah, there were all the damaged instruments. But now, musicians can’t play. They’re not making money. They definitely don’t want to spend money on repairs if they don’t have to.”

He says the first few months were okay. There were enough projects in the pipeline to keep him and his son Nicolo, who’s been helping out in the shop for the past eight years, busy and profitable. Though the work has slowed a bit recently, he assures me they’re still getting by; that despite the uncertainty of the coming months, he trusts God will see them through. A true Sicilian, it’s clear his Catholic faith is strong and ever-present. There’s a small metal crucifix nailed to his tool shelf; Bible verses grace his business cards and the tags in the instruments he’s crafted.

For all his endearingly familiar references to Antonio Stradivari, it is another luthier— Carlo Bergonzi, an eventual member of Casa Stradivari— to whom it seems Sal may relate a little more closely. While Stradivari was born wealthy, and therefore had the resources to relentlessly create throughout his lifetime, Bergonzi was restricted by the same financial limitations that so many Salvador Giardinas face today. As such, his name is less known— but his violins are all the more rare, and there’s inherent value in that. I have high hopes for the exceedingly rare Giardina violin in the works; for the day it receives its final layer of expertly-applied French polish; the day a fellow craftsman holds it in the sunlight and marvels, “A masterpiece!”

In the meantime, if you’ve got an instrument in need of repair, might I refer you to this magical little shop in Old Metairie? You’ll find it if you know where to look.