For 10 years I’ve lived on France Street, or within a block of it — in either the Bywater or Upper Ninth Ward neighborhoods. I’ve never had to rent a moving truck. When it’s time to move, I just kind of shuffle down the road with my clothes, silverware, books and bed.

After a decade, I’m pretty familiar with the street; six days a week I’m jogging down it. Seven days a week I’m biking down it. I know the best time and place to stand to get a down-wind whiff of The Joint’s early morning grilling, and I know the craters (aka “potholes”) by heart.

But, still, even the most familiar of things can surprise us with a mystery.

I was reminded of that when I stopped to consider four parallel cracks running down the middle of the road between St. Claude Avenue and Royal Street.

As I watched the cracks run straight down France Street, I wondered what could be causing such a uniform blemish.

Is it from the constant weight of cars rolling over the road? Is it the byproduct of some old street expansion project? Or, as was suggested by Edward Branley, local author of several books including “New Orleans: The Canal Streetcar Line — was France Street hiding some other secret of history?

“Those cracks look like they have street rail origins,” Branley explained. “Streetcars once spread to every corner of the city. But then buses replaced that system, and — in the case of a lot of backatown lines — the city would just pave over the tracks. With our heat and humidity, the rails would expand and contract, causing cracks to surface.”

It makes sense. There’s evidence all over the city of a much larger streetcar system. I’ve gotten my bike tire caught in the tracks — through a resurgent neighborhood — on Erato Street. I’ve spotted tracks ripping through crumbling streets in Central City, as well as old streetcar barns — including one that’s been converted into a Magazine Street grocery store.

If I wanted to determine where streetcar tracks currently sit below the street’s surface, I needed to understand where they’ve been. So I talked to several experts, and consulted Louis C. Hennick’s comprehensive work, The Streetcars of New Orleans.

What I learned is an incredible history, only a fraction of which I had ever heard.

Modest Beginnings

Railway technology really began to spread across the globe in the 19th century with the convergence of Industrial Revolution-era technological advancements like wrought-iron, grooved wheels and improved steam engines. The first railroad track opened in the United States was in 1830, beginning in Baltimore Harbor, and — decades later — connecting the city to the Ohio River.

Way down south, New Orleans was only just months behind.

It happened during a fantastic decade of growth for the city. In 1830, New Orleans’ population was 46,082. Just ten years later that number would explode to 102,193. As the population increased, residents would spread outside of the usual downtown neighborhoods.

Most New Orleanians believe the city’s rail era began with the St. Charles streetcar line. Well, that’s actually incorrect!

In fact, local rail history doesn’t begin with the streetcar at all. It begins with the Pontchartrain Railroad and the legendary Smoky Mary.

The “Daily Picayune” reported “the axe was driven into the first tree” in March of 1830, as the Pontchartrain Railroad Company cleared land for the track. Within the year, rails were laid through marshes and over swamps, and — on April 23, 1831, as hundreds of curious onlookers gathered on Elysian Fields Avenue and Decatur Street — the first-ever rail trip west of the Allegheny Mountains took passengers the five miles north to the lakefront town of Milneburg.

The trip didn’t go exactly as planned, however. The locomotives ordered from Great Britain hadn’t yet arrived, so the first 17 months of service were horse-drawn. It wasn’t until September of 1832 when the first steam-powered engine dragged 12 cars to Lake Pontchartrain.

New Orleans train travel was underway!

Making History

Just a year later, in 1833, serious discussion began on the creation of a street railway line. Surely that’s where the St. Charles streetcar line comes in, right?

Close, but still wrong!

The first streetcar line to open in New Orleans — which was actually the second to open in the entire WORLD (New York City to Harlem beat us by less than a year) — was the Poydras-Magazine route, which opened in the first week of January in 1835.

At the time, Carrollton was a suburb independent of New Orleans, and the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Company had a charter approved to build a rail line between the two centers. The line would include two branches off the main line, and one of those lines was the Poydras-Magazine Route — zig-zagging from Poydras Street, up Magazine Street, and over to the river and today’s Irish Channel.

A few days later, the other branch — called the “Jackson” line — began runnings its route from Canal and Baronne streets up to the Gretna Ferry terminal on Jackson Avenue.

A little more than nine months later, the charter of the New Orleans & Carrollton Railroad Company was fulfilled when the Carrollton Avenue streetcar line (now the famous St. Charles route) began its inaugural trip on September 26, 1835. Today, it is the longest continuously operating street railway in the world!

Fun St. Charles Streetcar Facts

Flagging down a streetcar is much easier now…

Here’s a message from Chief Engineer of the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad in the “Daily Picayune” on October 18, 1838:

“Those persons who wish to take passage in the cars at any intermediate stopping points between New Orleans and Carrollton, are particularly requested to make some motion or signal to the engineer of the locomotive previous to his arriving at that point in day-light; — after dark, it is necessary, in order that the engineer may stop, that a lamp should be held out.”

A pretty penny…

The fare in 1835, from Canal Street to Carrollton was $0.25, which wasn’t as cheap as it sounds. That’s $6.15 in today’s dollars, compared to the $1.25 it costs to purchase a ride on the streetcar currently.

Pick a train, any train…

In 1835, the Poydras-Magazine and Jackson lines were pulled by horse or mule. The main St. Charles (then called “Nayades Street”) line was mostly powered by British built steam engines creatively called “Orleans” and “Carrollton.”

There were eight round-trips between New Orleans and Carrollton each day. The first was horse-drawn, beginning at Carrollton at 4 a.m., and the rest were steam-powered with the final train leaving Canal Street for Carrollton at 9 p.m.

Streetcars, Streetcars Everywhere

By the 1840s, the city’s population was expanding uptown of the CBD, and as more houses were built along avenues like Napoleon and Louisiana, additional spurs were built along the Carrollton streetcar line to accommodate them. Increased density also increased complaints over steam-powered nuisances like soot and noise, resulting in a decades-long return to horse and mule-operated streetcars.

So far, all streetcar development took place uptown of the French Quarter. But that finally began to change in 1861 when a true city-wide streetcar system started to form.

Part of this was because builders began to see streetcars as a way to generate development rather than just to service already-established neighborhoods; and part of this was because competing railroad companies were formed to compete with the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad Company to create new lines.

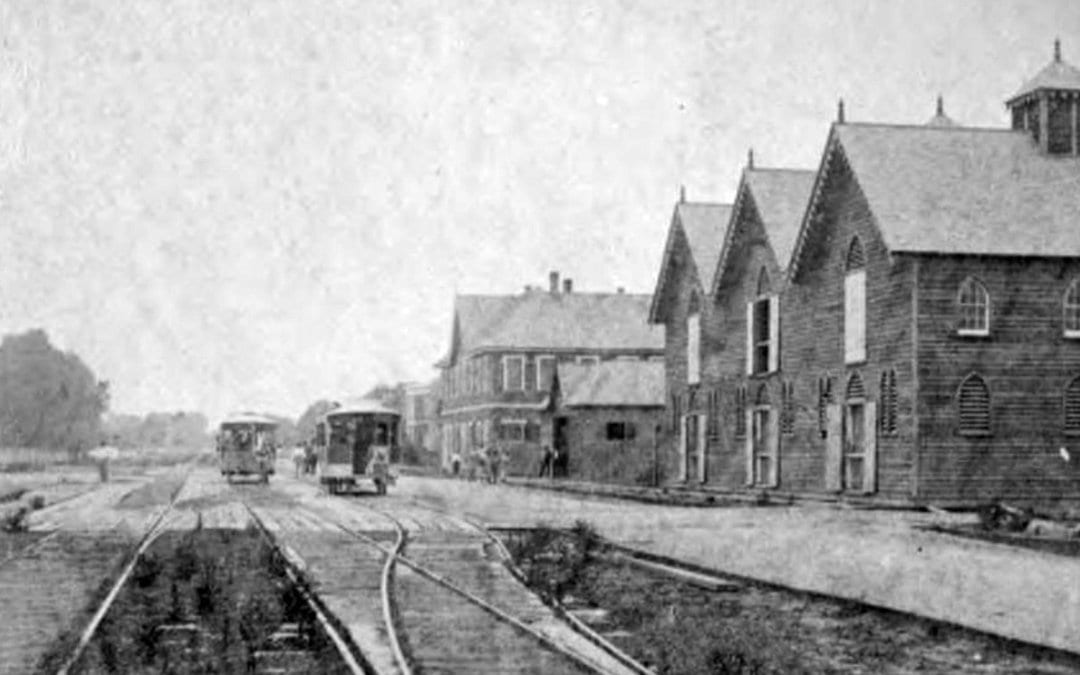

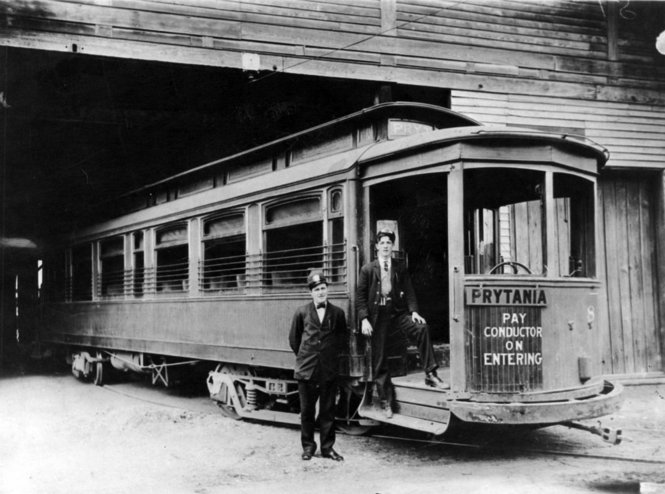

In June and July of 1861, alone, new streetcar lines began operating on Rampart and Esplanade street, Magazine Street, Camp and Prytania streets, Canal Street, Rampart and Dauphine streets, as well as over Bayou Bridge on Bayou St. John to City Park!

By the latter years of the 19th Century, there were six streetcar companies competing with one another for railway dominance. These included the white-painted cars of the St. Charles Railroad Company, the red of the Orleans Railroad Company, the orange and yellow of the New Orleans City Railroad Company’s stock, with the elder statesmen New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad Company adopting its current olive green and cream in the late-1890s. It must have been an incredible sight to see so much variety!

By 1882, there were 15 streetcar barns — including Arabella Station (now home to the Magazine Street Whole Foods) and Canal Station (now home to the Regional Transit Authority’s main office, as well as a bus and streetcar barn) — servicing those six different companies.

The streetcar system spread to every corner of the city, and the invention of electricity-powered streetcars — the St. Charles Line was electrified on February 1, 1893 — added speed without the nuisances of steam engines.. This was the same year the line expanded from the corner of St. Charles and Carrollton to a new streetcar barn on Willow Street.

The new barn — bound by Dublin, Poplar (now Willow) and Madison (now Dante) streets — replaced the New Orleans and Carrollton Railroad Company’s other three barns, two of which were on St. Charles and one of which was on Felicity Street. This barn remains intact today and over the years it has been used to store and service streetcars and buses, as well as to create new iterations of railway cars.

But this wouldn’t be the last time the St. Charles line — or the city’s streetcar line as a whole — would expand. At its peak, there were more than 225 miles of street railway serving more than 148 Million people per year! Unfortunately inefficiencies that resulted from the competing companies, as well as poor relationships with employees and the advancement of buses as a viable form of public transportation led to a streetcar decline so rapid it left the city with just one functioning streetcar line by the end of 1964.