Nathan Simpson looked at home amid the chaotic swirl of costumed revelers at the recent krewedelusion parade lineup, sporting a blue bodysuit and peering through glowing red lenses at the crowd. Tonight he was Recyclops, and he had a mission: to collect all the aluminum cans and plastic bottles he could get his hands on.

Simpson is one of about 20 members of the Trashformers, Mardi Gras’ first recycling-themed marching krewe. While recycling is the focus, the group, founded in 2019 by local architect Brett Davis, hopes to spark a broader conversation about Mardi Gras waste, including the plastic beads and throws now synonymous with the season.

Members dress in eco-pun costumes (Simpson’s Recyclops, inspired by Marvel X-Men superhero Cyclops, was joined by a Pacific Garbage Patch Kid and Oscar the Recycling Grouch), and deploy a fleet of lime-green shopping carts to collect cans and bottles directly from parade-goers.

Simpson, a New Orleans native, said he joined Trashformers to show that we can be responsible without killing the Mardi Gras fun. He grew up going to parades and loves Carnival krewes and balls, but the waste is a problem, he said.

It’s not about changing Mardi Gras, Simpson said, “it’s about changing the culture of how we experience Mardi Gras.”

Simpson isn’t alone. As New Orleans faces a host of ecological threats — climate change, sinking land and flooding to name a few — a growing number of locals are calling for an environmental reboot of the city’s Carnival experience, and a break from the throw-away culture and cheap plastic beads and trinkets ubiquitous at parades.

This year, several large krewes, including Rex and Bacchus, have publicized efforts to cut back on the amount of plastic members throw. Arc of Greater New Orleans, which sorts and re-sells beads, employing adults with disabilities in the process, reports donations more than tripled to 190 tons ahead of Mardi Gras 2020. Even the City Council weighed in, approving a new ordinance that bans riders from throwing the plastic bags that beads are packaged in.

Is a greener, plastic-free Mardi Gras possible? Sustainability advocates are optimistic, though they acknowledge it will require a major cultural shift. The answer is more complicated for krewes and riders.

“It’s about changing the culture of how we experience Mardi Gras.”

Cheap plastic trinkets underpin the economics of the season, allowing krewes to attract riders and generate revenue. Wholesalers make millions of dollars on the roughly 25 million pounds of beads imported from China every year, and parade-goers have come to expect a deluge of loot on the route.

Mardi Gras parades in New Orleans are big and bountiful, and that generates a lot of money for the city and local businesses, said Dan Kelly, president of the Krewe of Endymion, whose 3,200 riders each toss 500 pounds of throws on average. Kelly also owns Beads by the Dozen, a wholesaler that imports roughly 5 million pounds of throws each year.

“If you make it too expensive for people to throw these greatest shows on Earth for free, New Orleans is going to dry up,” Kelly said. “It’s not going to be the city that we’re known for.”

At the same time, the cost of cleaning up after parades is rising and taxpayers are footing the bill. The City of New Orleans spent $1.5 million to collect 2.6 million pounds of trash during the two-week height of Mardi Gras season in 2018, according to city records. That was a 60% jump in spending from 2008.

That price doesn’t factor in the toll Chinese-made plastic throws take on our health and infrastructure, said Dana Eness, executive director of The Urban Conservancy. Researchers have found unsafe levels of lead and a range of other toxins in imported beads, which can remain in trees, yards and sewers well after parades. In 2018, city contractors pulled 93,000 pounds of beads from clogged catch basins along the St. Charles Avenue parade route. The headline shocked locals and got national attention.

“The reality is there’s a huge cost that New Orleanians bear, but tourists do not, in terms of wear and tear on the infrastructure, clogged drains, flooding. Things we’re paying for in all sorts of ways,” Eness said.

Plastic beads remain plentiful and cheap

“The reality is there’s a huge cost that New Orleanians bear, but tourists do not.”

Plastic beads are a relatively recent Carnival addition. Kurt Owens, an interpretation assistant at The Historic New Orleans Collection, noted spectators gathered to watch the ornate floats, not catch throws, prior to World War II. Rex is credited with starting the tradition of throwing items to the crowd, beginning with the occasional glass bead tossed in the late 1940s, to the more abundant Czech crystals, and, in the 1960s, aluminum doubloons.

The appearance of molded polystyrene beads coincided with the rise of the city’s first superkrewes in the 1970s. Today, krewes work closely with wholesalers to purchase whole catalogs of Chinese imports that they then mark up and sell to members, a key source of revenue.

Alyssa Fletchinger, vice president of Plush Appeal, a throw wholesaler, said useful throws, including water bottles, umbrellas and flashlights, are a growing market. Still, price point is key, and beads remain cheap and abundant, she said. (A case of 60 dozen, standard 33-inch beads retails for about $36, or about 5 cents a strand.)

“Most organizations are trying to make it cost-effective for people to get up there and have a good time and have enough stuff to throw,” Fletchinger said.

Kelly said beads make up about three-quarters of sales at Beads by the Dozen, providing the cheapest way to get the throw volume many riders are looking for.

“When you ride a 5-mile parade route, you need a lot of volume,” Kelly said.

‘People are starting to pay attention’ to the waste issue

“People are just done with the plastic beads.”

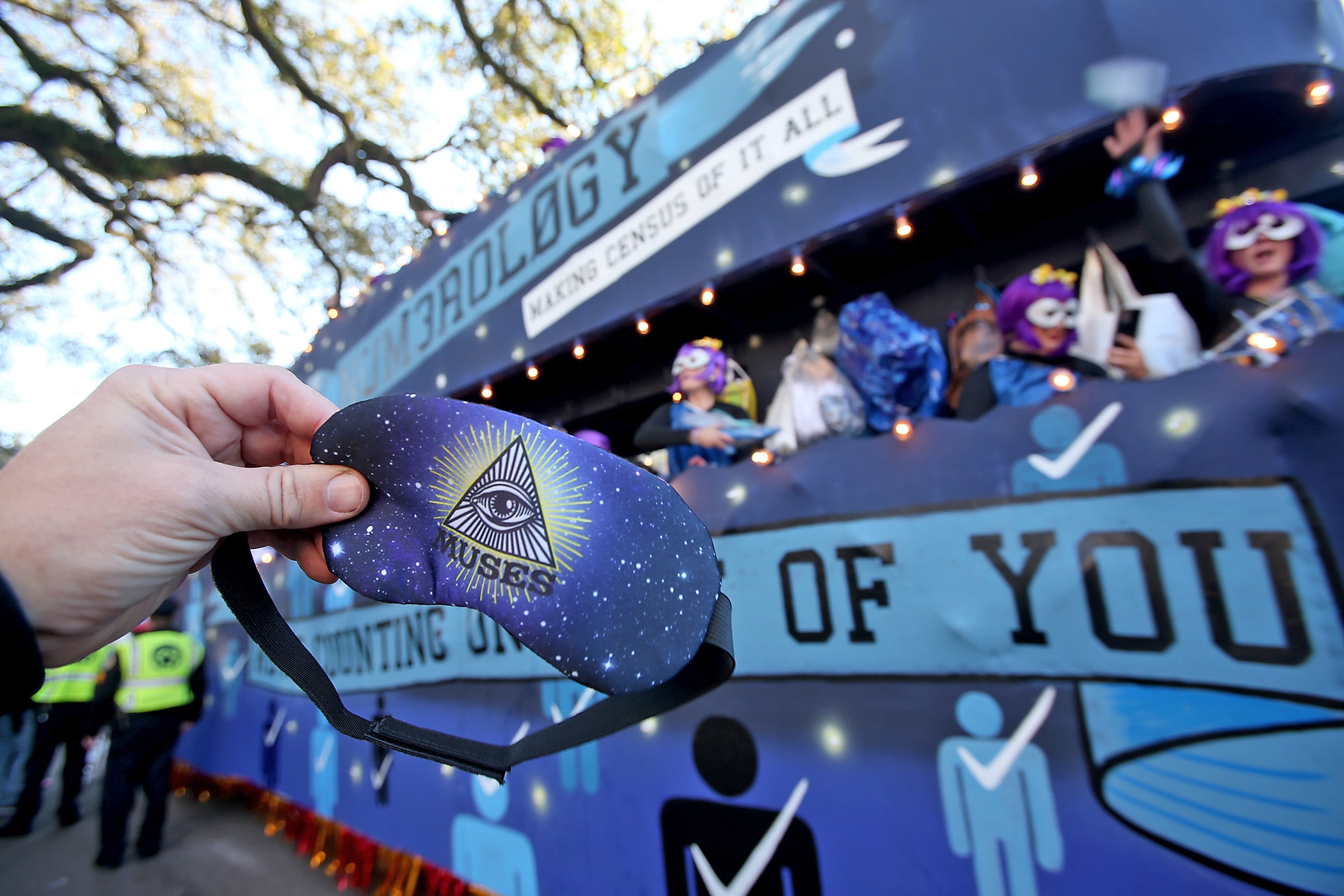

Some krewes have been more aggressive than others in cutting overall throws and stocking up on useful items. Downtown parades like Chewbacchus and Krewe du Vieux are largely throw-free. The Krewe of Muses still throws beads, but encourages members to embrace useful items. Its throws this year include hair ties, magnets and bicycle bells. Bacchus has cut its plastic bead throws by half since 2015, and will toss sustainable items like aprons, potholders and silicon wine glasses.

Rex will replace a third of its cup throws with reusable aluminum cups. It is also working with ArcGNO to buy back all Rex branded throws that are recycled, said Steven Ellis, Rex quartermaster. Ellis noted the krewe’s board pushed for a more sustainable approach to throws this year.

“No one wants a bunch of plastic stuff filling up catch basins and littering the city,” Ellis said. “For us it starts, first of all, with throwing things people want.”

Some riders are giving up plastic beads on their own. Many cite the disappointment of watching parade-goers avoid catching generic beads.

“People are just done with the plastic beads,” said Christian Moises, who rides with Krewe of Carrollton, which throws decorated mini shrimp boots in addition to typical plastic wares.

Moises, who spoke as a rider, not on behalf of the krewe, replaced his plastic beads with imported glass beads this year. Glass beads cost more, about 45 cents per strand, but the crowd goes crazy for them, he said.

Dian Winingder, a float captain in the Krewe of Iris, said this is the third year her float won’t be throwing any plastic beads, opting for items like playing cards, umbrella hats and Rubik’s cubes instead.

“I just think we’re at a pivotal point and people are beginning to pay attention… I know the change is coming,” Winingder said.

Sustainable throws seek to meet shifting demand

“Finding and inventing throws that are a higher value…”

That’s where locally-made, sustainable throws come in, said Brett Davis, who heads Grounds Krewe, a nonprofit dedicated to reducing Mardi Gras waste, in addition to Trashformers. Grounds Krewe coordinates on-route bead recycling efforts, and debuted a sustainable throw catalog last year, which has found success selling bamboo toothbrushes, pencils and wooden yo-yos to riders.

Recycling plastic beads is a good short-term fix, but “finding and inventing throws that are a higher value to the thrower and catcher is a better solution,” Davis said.

This year, Grounds Krewe’s catalog expanded to include burlap sacks filled with jambalaya mix, red beans or dark roast coffee. The packaged food throws are sourced from Louisiana companies, small enough to throw, and generically branded in order to comply with city code, which bans commercial influence in parades, Davis said. The group sold about 8,000 of the food throws this year.

Atlas Handmade Beads sells necklaces and bracelets made out of paper beads handcrafted in Uganda. The pieces and their story are “a conversation starter,” and meant to be worn well after Mardi Gras, founder Kevin Fitzwilliam explained. He plans to expand to small, throwable purses as well.

Davis and Fitzwilliam acknowledge that their throws don’t compete with imported plastic beads on price. A 50-count bag of the red bean throws retail for about $88, or $1.76 a throw. Atlas Mardi Gras necklaces sell for $12 each online, though Fitzwilliam noted riders get bulk pricing that lowers the price to less than $3 per piece. But they appeal to a rider who wants something more, and they show what’s possible with less plastic, Davis said.

“Mardi Gras was a huge and successful revenue generator before superkrewes started unloading plastic on us as fast as they could … There’s no reason to think it can’t be successful after that,” Davis said.

City leaders say tackling Mardi Gras waste issue is a priority

“We are already an environmentally fragile city and region… We need to put our money where our mouth is…”

The good will around Mardi Gras sustainability needs the backing of a city-led initiative if it’s going to stick, said Eness, with the Urban Conservancy. She draws comparisons to the 2015 citywide smoking ban, which seemed a long shot before receiving broad support.

“As this conversation matures, it’s really going to have to become about collective public action,” Eness said. “That’s where city government really has to become more involved as players in terms of setting policy and working with people.”

New Orleans City Councilman Jay Banks, who led efforts to pass the plastic bag rule in January, noted the ordinance resulted from a collaborative effort, involving input from City Hall and krewe leaders. There’s more work to be done, Banks added.

“We’ve got to manage it as best we can, and that’s what we’re trying to do,” Banks said. “If we can address the litter on the front side, it makes it easier to deal with on the back side.”

Parade permit fees are perhaps one of the biggest flashpoints as New Orleans confronts the waste issue. The largest superkrewes pay $1,500 to parade, which is little more than the price Sunday second lines pay. Sustainability advocates think that’s far too low. In general, krewes are opposed to the move, which they say would make it harder to put on free parades, which generate tax revenue in the form of hotel stays and sales taxes.

Ramsey Green, who oversees infrastructure and resiliency efforts for Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s administration, said City Hall is committed to addressing the waste issue, including analyzing parade permit fees.

As 2020 parades ramp up, Green said the city is focused on practical measures, including promoting bead recycling through ArcGNO and placing catch-basin covers along the full length of the St. Charles and Endymion parade routes, as well as enforcing existing policy, for example, ensuring parades have proper sanitation contracts in place before they can get a permit to roll.

“We are already an environmentally fragile city and region … We need to put our money where our mouth is and do something about this,” Green said.

Going back to basics

The experience of giving handmade items is more meaningful… “It culminates the spirit of the season,”

For New Orleanians like Vanessa Thornton, the key to a greener Mardi Gras is rooted in the past. The season has always had a handmade quality to it, especially for the city’s African American community, said Thornton, pointing to the Mardi Gras Indian and baby doll traditions.

Thornton, whose mother, Eva “Tee-Eva” Perry masked as a baby doll alongside Antoinette K-Doe, makes handmade pillows to hand to spectators. For Thornton, now a grandmother, Mardi Gras isn’t about throws; it’s about “dancing to the music and feeding your people.”

Alana Harris, founder of the Creole Bell Baby Dolls, hands out handmade yarn dolls as well as dried flowers when she masks. The experience of giving handmade items is more meaningful, Harris said.

“It culminates the spirit of the season,” Harris said.

Owens noted the Zulu Social Aid & Pleasure Club turned heads in the 1930s when it started throwing gold-painted walnuts to crowds. Today, the season’s most coveted throws continue to be custom and often handmade, from Zulu coconuts to glittering Muses shoes.

“I think the krewes are challenged in some ways to try to come up with providing a desirable souvenir,” Owens said. “The throw beads are on their way out.”

How can you make your Mardi Gras more sustainable?

Advocates for a greener Mardi Gras note that individuals play a big role in changing the culture that results in waste. Here are a few tips for reducing your Carnival footprint.

Recycle your beads.

Stephen Sauer, executive director of Arc of Greater New Orleans, said the organization has more than 100 bead recycling bins placed through the New Orleans and surrounding suburbs. Here’s a map of year-round bin locations.

Also, look for volunteers with Grounds Krewe, a nonprofit dedicated to reducing Mardi Gras waste, on Thoth Sunday, which falls on Feb. 23. The group will be handing out bead recycling bags and manning on-route drop-off sites for bead recycling through ArcGNO.

Host a bead drive.

Sauer said ArcGNO is able to support bead drives hosted by schools, churches or even individuals. Contact ArcGNO to obtain a bead collection bin (or set out your own), and Arc will come by and pick up donations, he said.

Bag your trash.

It’s tempting to leave used cans, bottles, cups and food containers on the ground once parades are over, but all it takes is a strong gust of wind to push that trash into a nearby sewer drain. Take time to pick up and bag your trash. Better yet, pack it out with you.

Buy sustainable throws.

If you ride in a Mardi Gras krewe, make an effort to buy recycled beads and consider swapping traditional beads out for sustainable throws, like glass beads or handmade items.

See something, say something.

Disturbed by a particularly large pile of trash on the parade route? Saddened by a tree weighed down by beads? Enamored with the ingenuity of a particular reusable throw? Brett Davis, founder of Grounds Krewe, suggests taking a photo with your phone and sharing it on social media or starting a conversation with friends. “Talk about it,” Davis said.

Share your thoughts with city leaders.

Want to see more action on Mardi Gras waste? Write to your City Council representative as well as Mayor LaToya Cantrell’s office, and share your thoughts. Ramsey Green, head of infrastructure for Cantrell, said City Hall wants to hear what residents think about Mardi Gras waste.

Green said residents can send questions and concerns [email protected]. Click here to find contact information for your City Council representative.