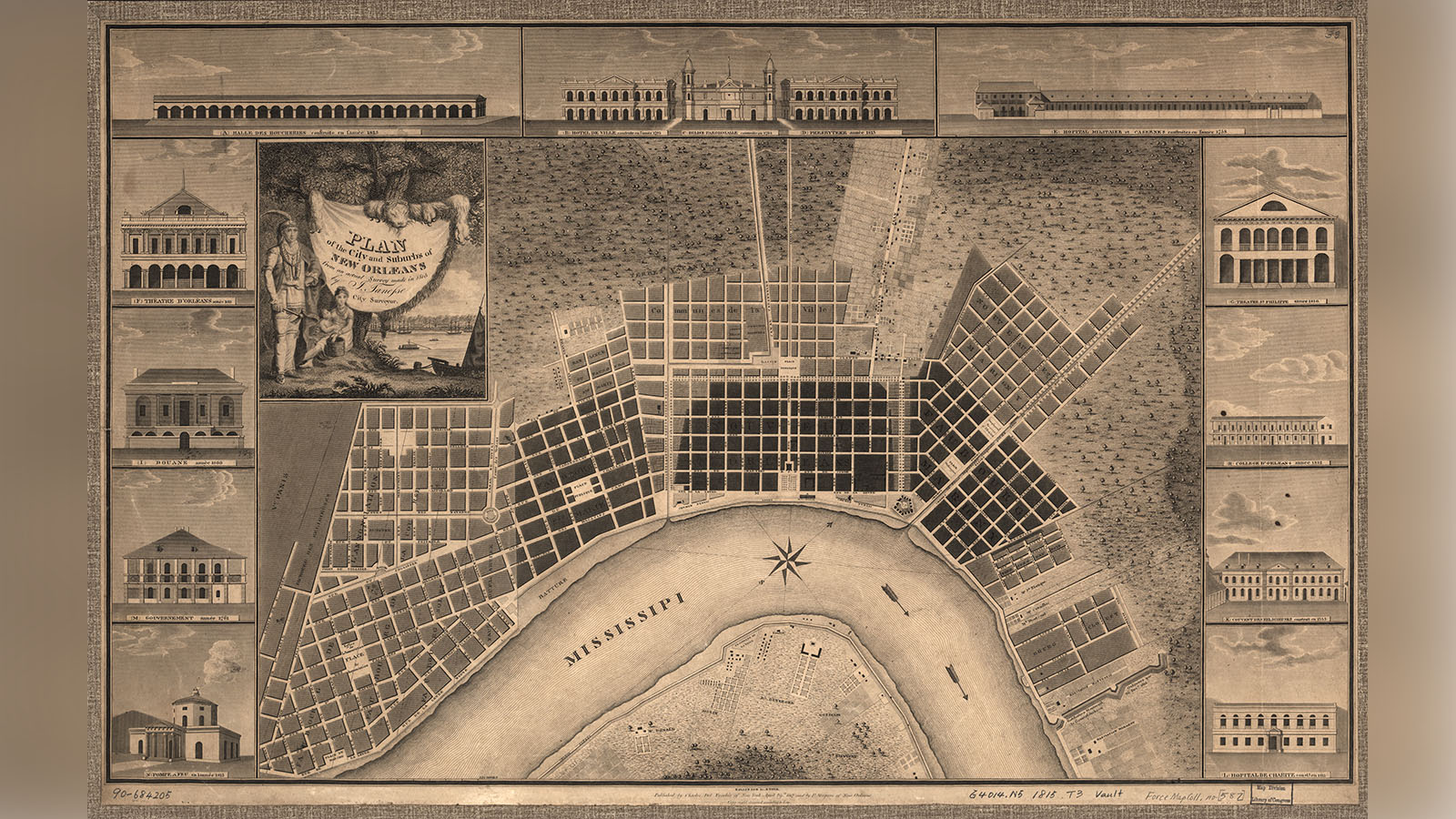

Cover photo courtesy Library of Congress, Geography and Map Division, Louisiana: European Explorations and the Louisiana Purchase.

History is a funny thing. The smallest, most seemingly insignificant events can change the course of it, and often do. Here in New Orleans, a failed canal building project rearranged the city’s fate and created some of its most famous features.

The Importance of Infrastructure

Jean Baptiste Le Moyne de Bienville founded New Orleans in 1699 partly based on its strategic position on the Mississippi River. The city was to be built on the high ground of a defensible curve of the river, and the fact Lake Pontchartrain (and from there the Gulf of Mexico) was accessible via the nearby Bayou St. John added an economic incentive. Even then, France knew a navigable canal from the lake to the river would increase shipping and allow for faster travel.

After the city was transferred to Spain, Gov. Fransico Luis Hector, Baron de Carondelet, did much to improve the region’s quality of life. In 1794, he ordered a 1.6 mile canal to be dug from the fledgling city to the bayou. The move increased drainage around the city and connected New Orleans to Bayou St. John. Two years later, the Cabildo officially voted to name the waterway the Carondelet Canal.

The newly formed Orleans Navigation Company began making improvements to the canal in 1805 and, though it took a decade, helped the canal become an important shipping lane to the “backatown.” Small craft brought cotton, tobacco, lumber, wood, lime, pitch, tar, brick, sand, oysters, furs and pelts into the city via the Carondelet. Unfortunately, because of the lack of the natural flow of water, the waterway was often clogged with plants and garbage. Adding to its decreased navigability was the fact the canal backed up during heavy rains and contributed to flooding.

Partially due to these problems, a second canal, wider and deeper to allow for sailing vessels, was dug in the 1830s by masses of newly arrived Irish immigrants. The New Basin Canal proved extremely popular and immediately after it opened, the Carondelet Canal (or Old Basin Canal as it came to be called) saw business plummet. The Carondelet continued to function into the early 1900s due to its being positioned near the center of what is now the French Quarter.

Massive Changes for the City

The Louisiana Purchase was completed in 1803. The sale essentially doubled the size of the United States and provided the new nation with several important shipping lanes, including the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers. Like any nation, the United States was seeking to improve its economy and began shipping and importing through the recently acquired Port of New Orleans. However, the Mississippi River remained nearly impossible to sail upstream. Once again, calls for new navigation channels in New Orleans were sounded.

The city had a population of only 8000 when the U.S. acquired it. Within 20 years, the population had exploded to 100,000 and the struggle for cultural control of the city was evident in everything from where one chose to live to what language they spoke. The Commons, as it was called, was just one more way to divide the Anglo-Americans and the Creoles.

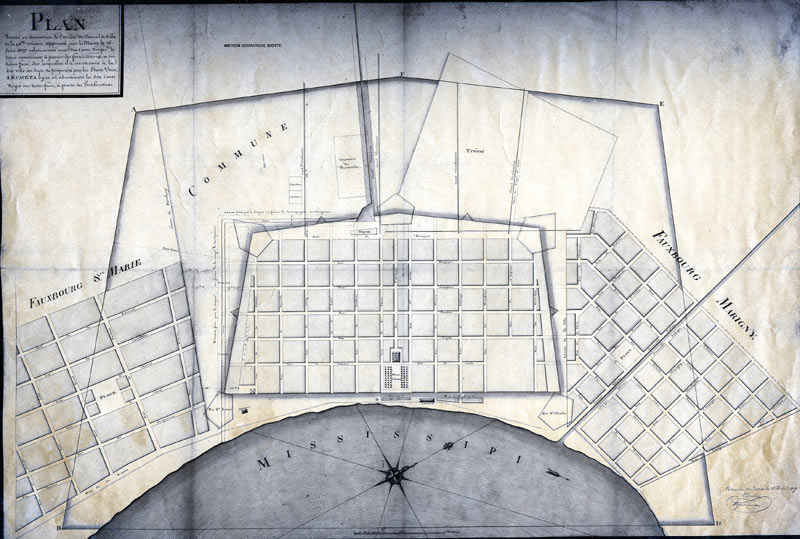

The City Commons, a 600-yard piece of land, surrounded the French Quarter and separated it from the Faubourg St. Marie, today’s Central Business District. The land belonged to whichever monarch currently ruled the colony, and when the United States acquired Louisiana, the land was placed under governmental control. New Orleanians objected to the Commons being taken, and the resulting appeal was heard by Congress in 1807.

In March of that year, Congress signed into law an act which ceded the Commons to the City of New Orleans provided the city allocate 60 feet of it for a new navigation canal. The President of the Orleans Navigation Company, James Pitot, wanted to join the new canal to the already existing Carondelet Canal, effectively creating a passage from the Mississippi River to Lake Pontchartrain. But plans had to be made first and for that the city turned to Jacques Tanesse.

A 60-Foot Wide Median

So, if the plans were made in 1810, why had ground still not been broken in 1837? Several reasons, including various lawsuits involving the Orleans Navigation Company. But perhaps the biggest obstacle to digging the waterway was the canal itself.

A 60-foot wide body of water in the middle of what was becoming a major thoroughfare would bring the risks of more frequent flooding and stinking, stagnant water breeding disease. Of course, that’s also without factoring in the high, narrow bridges needed to cross over the canal into the American Sector or French Quarter while ships sailed beneath.

In the years of waiting for a canal to be dug, the street itself picked up the name and Canal Street became more and more populous, even without developing the wide median.

As the canal project stalled, tensions between newly arrived “Americans” and the French speaking Creoles steadily grew. The opposing groups fought for political, cultural and economic power, sometimes by throwing bricks in the street. In 1836, the Louisiana Legislature divided New Orleans into three sections, allowing each to govern themselves in an effort to keep the city from tearing itself apart.

The First and Second Municipalities (today’s French Quarter and Treme neighborhoods) were primarily Creole while the Third (today’s Central Business District) was primarily Anglo-Americans. Canal Street became a natural dividing line between the feuding ethnicities. It was into this hostile atmosphere that the term “neutral ground” was brought into the city. Taken from the name for the demilitarized zone between Mexico and the United States, the 60-foot wide median became known as “neutral ground” separating the Creoles and Anglo-Americans.

Though relations between the two groups slowly improved, the term never left. Nearly 200 years later, New Orleans’ neutral grounds are no longer the battleground the original Canal Street was. Now they play host to the battle for Mardi Gras throws instead.