“I’m going to see this woman up close

Including the accursed devices

Ended up doing an infamous

Of the one I once loved;

She is dangerous, she is beautiful,

But I do not want to be afraid”

– Micaëla’s Song from the Opera “Carmen”

Hear now the tragic tale of one Marguerite O’Donnell, born in New Orleans in 1842, the youngest of twelve children of recent Irish immigrant Michael O’Donnell and his French wife. She was the only one of the couple’s seven daughters to inherit her mother’s French beauty. At the age of 18, she married Octave Sauvé, but before she had much time to enjoy marital bliss, Octave went off to fight in the Civil War. The war devastated Marguerite’s family; all five of her brothers as well as four of her sisters’ husbands were killed in the fighting.

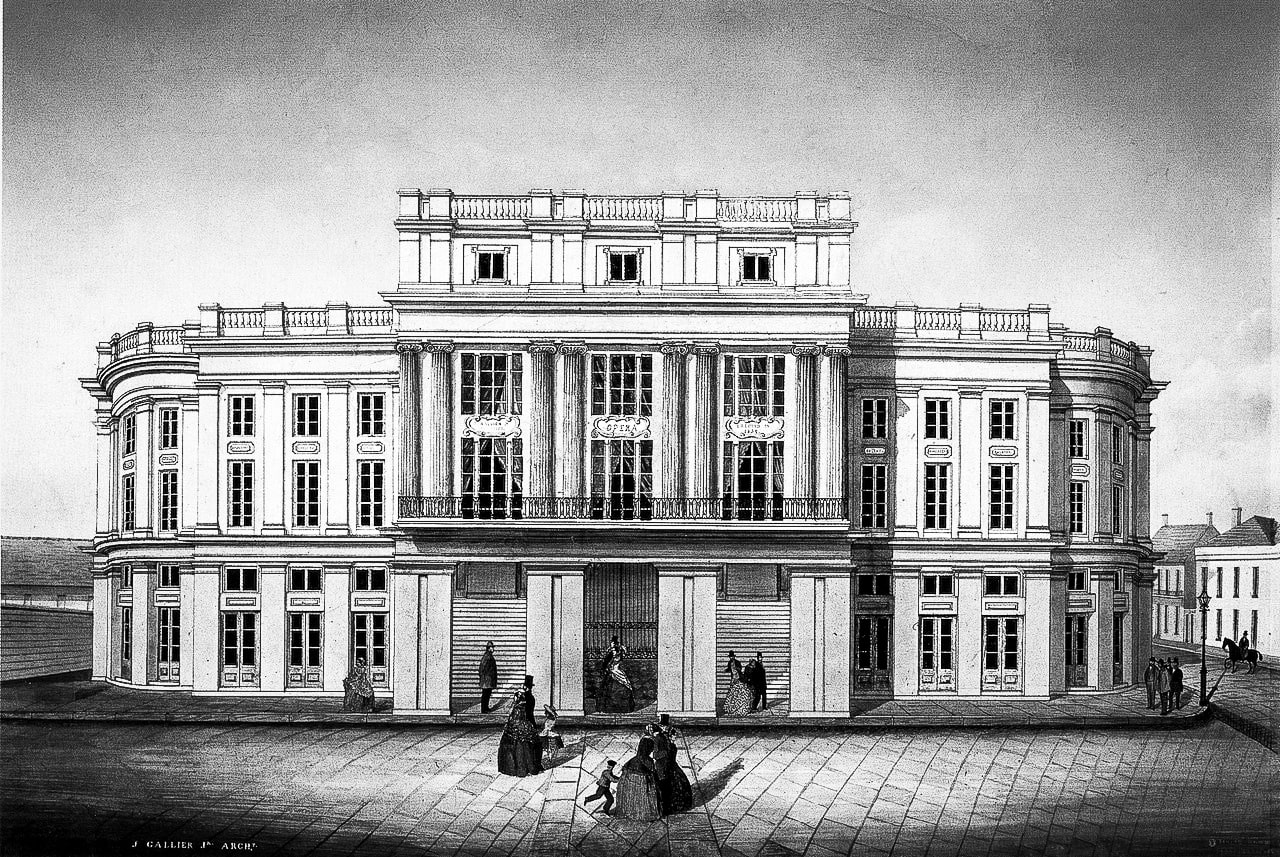

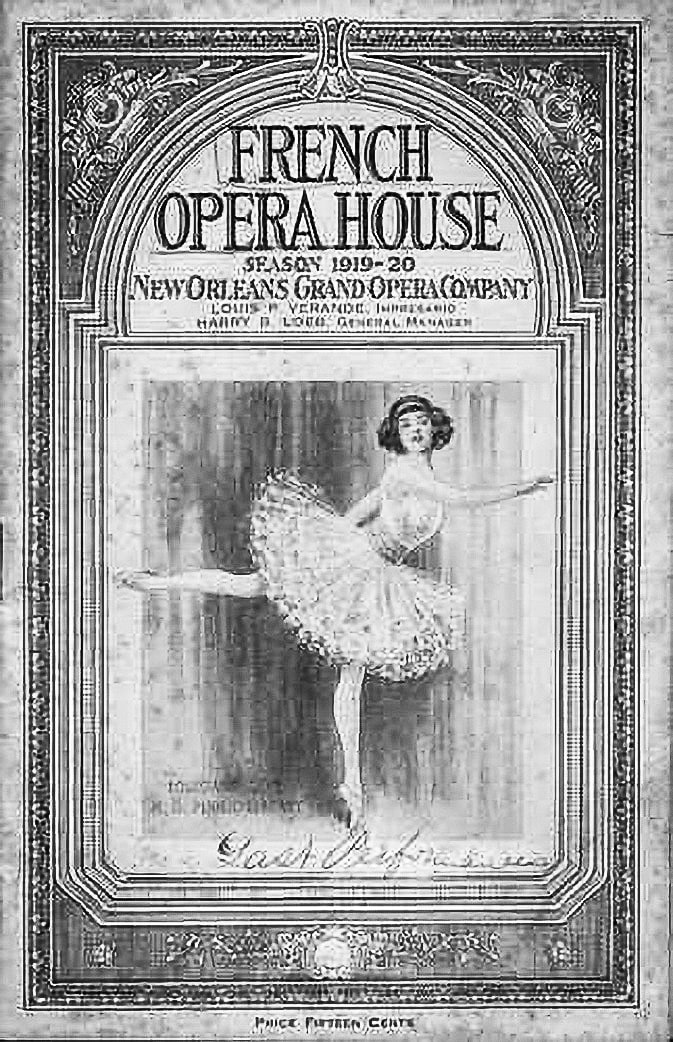

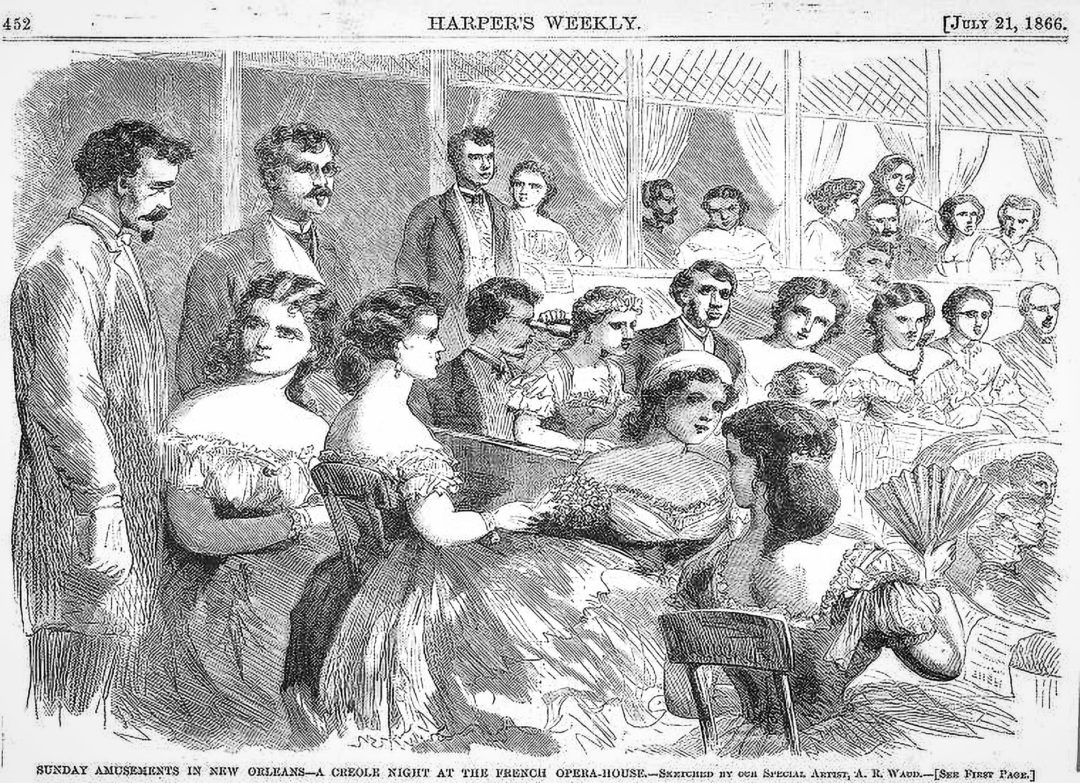

Her husband, however, survived the fighting but returned to Marguerite a broken and cruel man. Unable to stand being in the house with him, she went to work as a chorus girl at the French Opera House on Bourbon Street, lying about her age by saying she was in her early twenties (by then she was 33). The French Opera House, designed by famed New Orleans architect James Gallier Jr., had opened in 1859 in the 500 block of Bourbon Street and was the pillar of Creole society for the rest of the century, hosting Carnival balls and performances by the biggest names in entertainment. Marguerite kept her opera house gig secret from her husband, which was easy enough because they both worked at night).

Marguerite performed at the opera house for several years until the summer of 1878 when yellow fever arrived once again in New Orleans. The epidemic finished what the Civil War started, killing the rest of her family, including her husband Octave. Madame Marguerite Sauvé was now alone but continued to perform for many years at the French Opera House, an aging showgirl hanging on too long, like Lola from that Barry Manilow song that haunted me as a child.

From the chorus to the kitchen

At the turn of the century, Marguerite became the paramour of an elderly, rich, and slightly blind man named Monsieur de Boisblanc who lavished her with finery before conveniently dying three months into their affair. She used the $10,000 inheritance he left her to open a pastry shop she named Les Camelias. It was located just around the corner from the French Opera House where she had performed for so many years and it was a popular spot for the opera crowd to score a delectable dragée, gateau chocolat, or pâte brisée.

Her shop was so successful she put an ad in papers across the South seeking another pastry chef, settling on a 21-year-old from Tampa named Carlos Alfaro, purportedly a relative of the President of Ecuador, General Elroy Alfaro. (Author Googles dates of Elroys’s reign. Checks out.)

So the handsome, young Carlos shows up in New Orleans, and of course, sucks at making pastries, but in the shadow of the French Opera House, music and passion were always the fashion. The young pastry chef and 60-year-old former showgirl began a love affair.

The betrayal

Marguerite was no longer alone. She’d been loved first by a Civil War soldier, then an old man and finally a young man. In the olden days this trifecta was called a “Reverse Scarlett O’Hara.”

And they lived happily ever after!

No, of course they didn’t, of course he did, of course she found out, because this is how these ghost stories tend to go. Carlos had taken up with a streetwalker named Lisette Lebouef and the pair had a love nest on St. Ann Street at Rue Royale just a few blocks from the pastry shop. After popping into the rooming house one day and finding the pair asleep in each other’s arms, Marguerite’s heart was broken.

She lost her youth, she lost her Carlos, now she’d lost her mind.

Marguerite returned to her home above the pastry shop. There was blood and a single gunshot as she killed herself with a pistol. In the suicide note left for police, Marguerite swore her spirit would return for vengeance.

Marguerite’s ghostly revenge

A few days after Marguerite’s suicide, late night revelers on Bourbon saw an eerie sight on the steps of the French Opera House: a pale woman with red, glowing eyes set in a sunken face, her long, white hair streaming down her back and dragging along the ground. The apparition glided down the steps to Bourbon, made a right on Toulouse, a left on Royal, and passed behind St. Louis Cathedral before turning onto St. Ann.

Residents of the rooming house saw the ghost come into the building and up the stairs. One girl later declared the apparition to be none other than Marguerite, late of the Les Camelias pastry shop. The ghost slipped into the room where the lovers slept and cranked up the gas on a small stove, killing Carlos and Lisette. After getting her revenge, the ghost of Marguerite slipped back into the night. But it wasn’t the last she was seen.

For ten years, Marguerite’s nightly procession from the opera house to the St. Ann rooming house continued. Sightings of the ghost of Marguerite were so frequent, one of the local newspapers wrote about them. Neighbors dubbed Marguerite’s ghost “The Witch of the French Opera House.” Finally, after a decade of haunting, yet another new tenant moved into the cursed apartment where the couple was murdered because there was no such thing as Zillow back then. The new tenant found a piece of paper wedged between the mantel and the brick of the chimney, supposedly a love letter from Marguerite to Carlos begging to be taken back. The new tenant tossed the letter in the fire and as she did so, the ghost of Marguerite suddenly materialized and tried in vain to save it from burning. As the letter crumbled to ash, the ghost let loose a tortured howl and disappeared, never to be seen again.

Or maybe not.

Some claim she can still be seen walking her forlorn route, tormenting unfaithful lovers. Others say Marguerite continues to haunt the rooming house, becoming particularly restless when another woman is in the building.

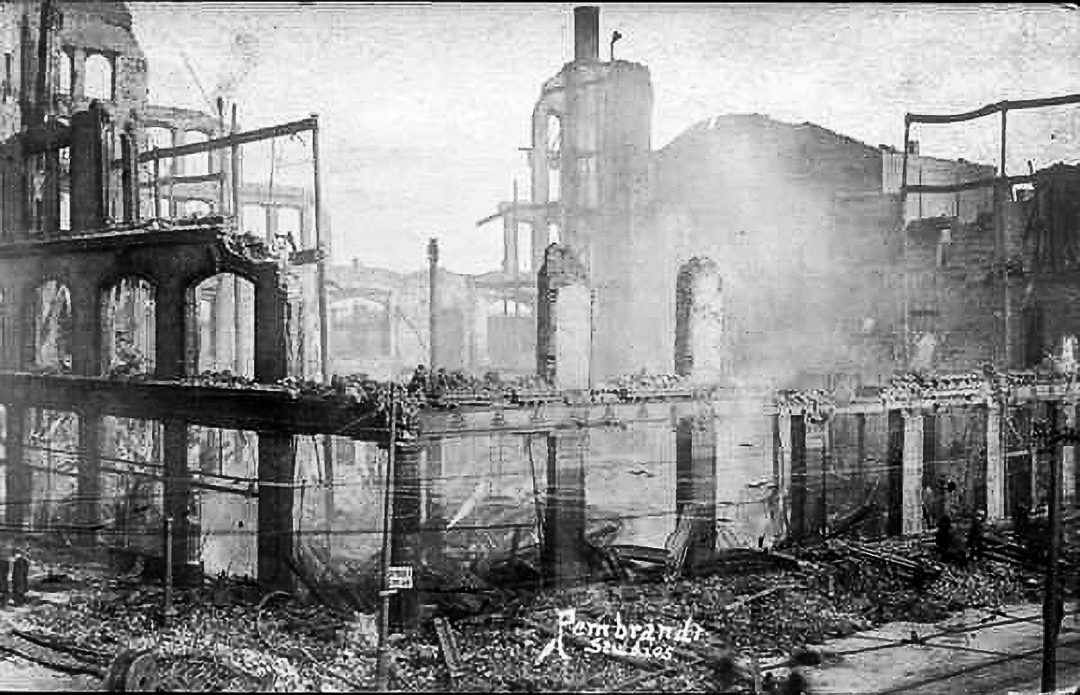

And what of the French Opera House, the hottest spot north of Havana and Marguerite’s starting point for her decade of ghostly treks through the streets of the French Quarter? In the early morning hours of December 4, 1919, a mysterious fire broke out and destroyed the entire opera house, leaving a scene of destruction one reporter described as “a bombarded cathedral town.” (War imagery was kind of a thing in 1919.) The fire occurred hours after a rehearsal for the opera Carmen, the story of a fiery-eyed performer caught in a love triangle that ends in her violent death… sound familiar?

References

Campanella, Richard. Remembering the Old French Opera House. Preservation in Print, February 2013.

deLavigne, Jeanne. Ghost Stories of Old New Orleans. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1946

Martin, Amy. Witch of the French Opera. October 31, 2017. https:\\moonlady.com/witch-of-the-french-opera/ Accessed August 2021

Opera-Arias.com. https://www.opera-arias.com/bizet/carmen/je-dis-que-rien-m’epouvante/ Accessed August 2021

PBS. The Great Fever / 1878 Epidemic. https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/fever-1878-epidemic/ Accessed August 2021

Quackenbush, Jannette. Ghost Stories and Folk Tales of New Orleans. Creola, Ohio: 21 Crows Dusk to Dawn Publishing, 2021

Saxon, Lyle, Dreyer, Edward, & Tallant, Robert. Gumbo Ya-Ya. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing Company, 2012

Schlosser, S.E. Spooky New Orleans. Guilford, CT: Globe Pequot, 2016