In 1852, one Archie Griffon built a spacious, stately home in the 1400 block of Constance Street. Four huge columns welcomed guests into a mansion which featured large rooms with 14-foot ceilings suitable for fancy parties and general high society merriment. Under this grand roof, they “bon temps roulezed” until the Civil War intervened.

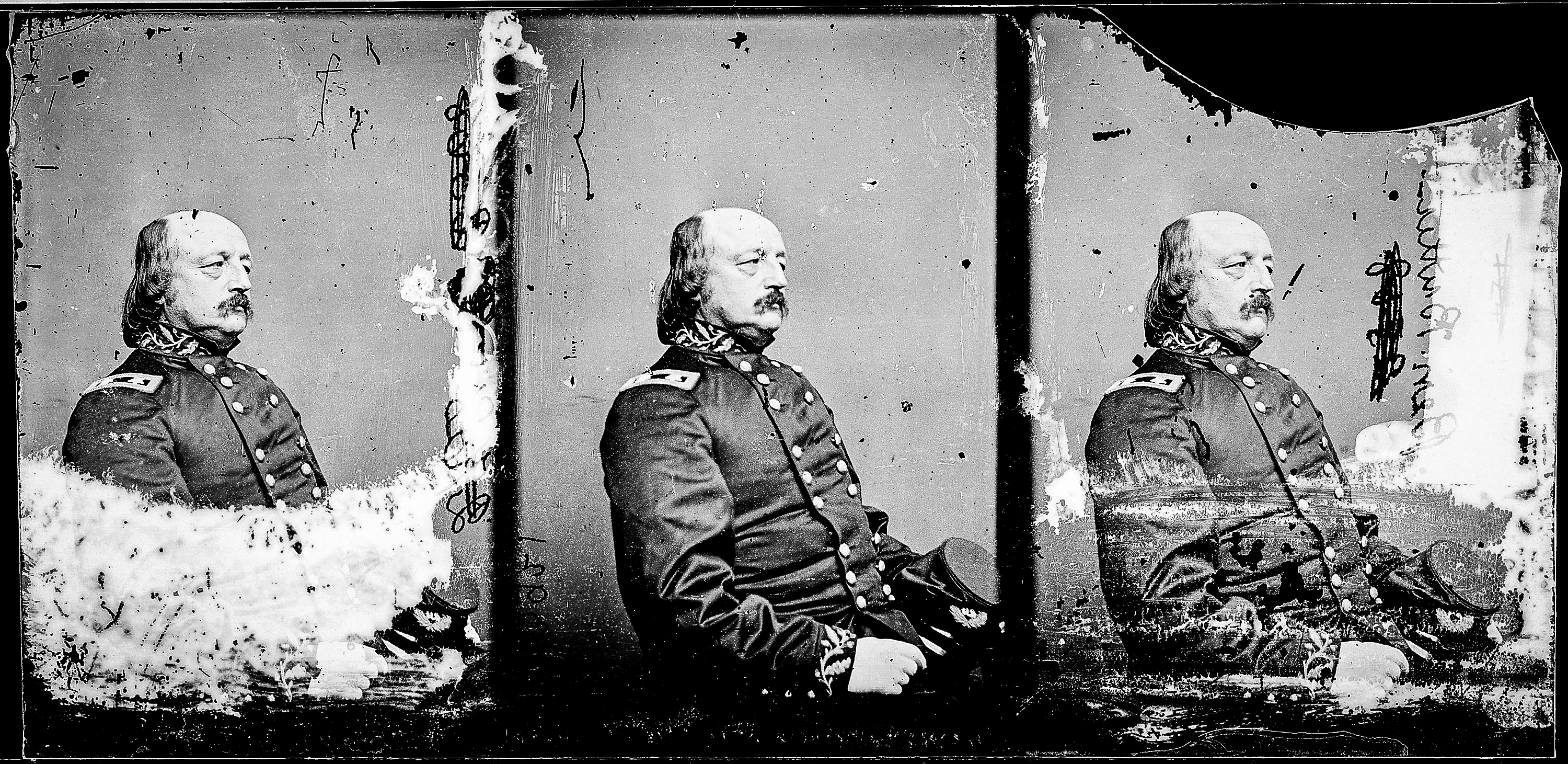

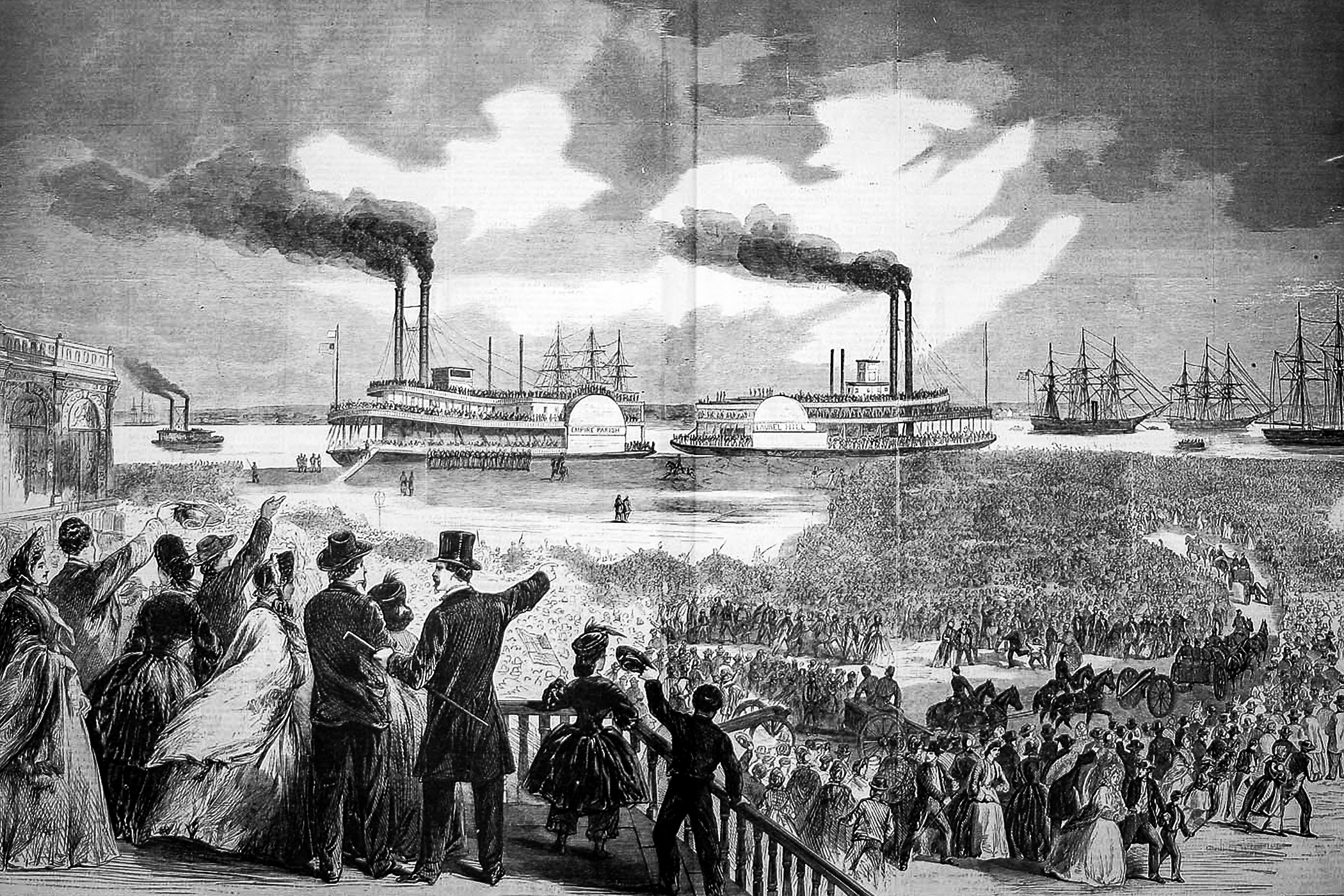

When Union General Benjamin Butler entered New Orleans on May 1, 1862, Griffon is said to abscond from the house. Why he left became fodder for speculation. Some said it was fear of the wrath of the Union soldiers, others said it was because of the evil those soldiers found in his attic when they requisitioned his mansion as a billet…

The attic of doom

Upon arriving to occupy the mansion, Union troops heard terrible moaning and the clanking of chains emanating from the third-floor attic. Creeping up the stairs to investigate, they were met with the horrible sight of around a dozen malnourished and abused slaves chained to the wall, abandoned to their fate by their cruel master. There was suspicion that terrible medical experiments had been inflicted upon them. Some were in such poor condition they did not even survive their relocation to a military hospital.

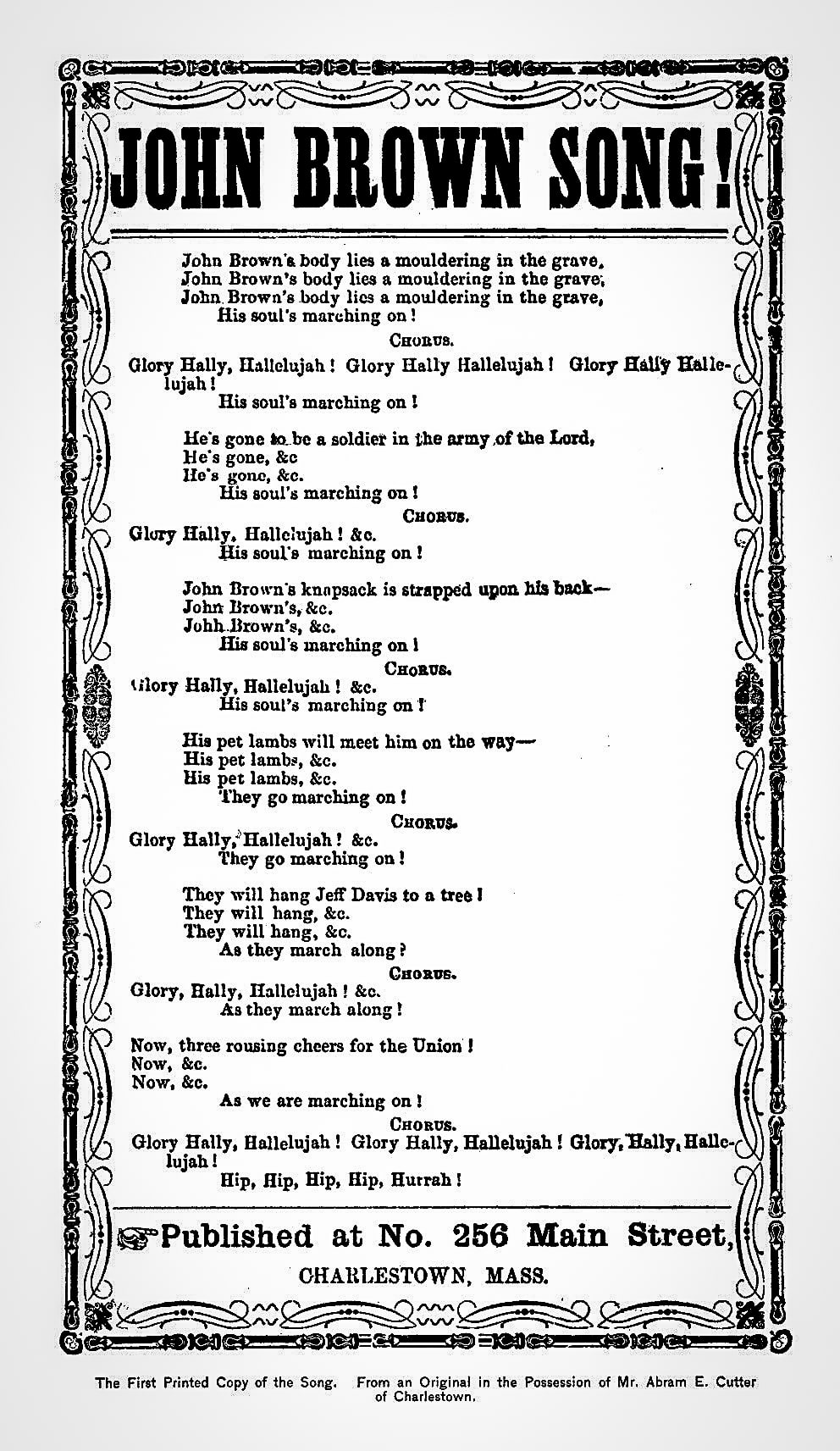

Griffon House was given over to the Union troops as a barracks, with the dreadful attic converted to a holding cell for prisoners. In the ensuing days, two soldiers in Union blue were arrested for looting and confined to the makeshift prison. They spent their days drinking whiskey with their guards and belting out Union marching songs like “John Brown’s Body,” singing:

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

John Brown’s body lies a-mouldering in the grave,

His soul’s marching on.

But the two prisoners had a secret…they were not Union soldiers at all, but Confederates in stolen uniforms. They believed their only hope of survival was to stay locked up and convince their captors they were one of them.

But their luck ran out.

It turned out that General Butler had ordered that anyone caught looting New Orleans, regardless of their uniform, was to be executed. The two soldiers, realizing they were doomed, paid off one of their guards and were handed a pair of pistols. That night, sitting on a mattress, each pointed their pistol at the other man’s heart and pulled the trigger after agreeing if it was “1, 2, 3, SHOOT” or “1,2,3!”

After their hearts were pierced with bullets, they bled profusely, exsanguinating through the floorboards of the attic into the house below.

Another version of the suicide story says the two men were actually Union soldiers Capt. Hugh Devers and Quartermaster Charles Cromley who got caught trying to rob the Union payroll to pay off their debts from gambling in the French Quarter and subsequently shot each other to avoid the humiliation of prosecution. Either way, you got uniformed ghosts.

(National Archives via Wikimedia Commons)

Chains clanging, bricks flying

Griffon House was used commercially in the post-war years, serving as a perfume factory, a union hall, a mattress factory, and a lamp factory. It also became the source of many spooky happenings.

In the 1920s, a handyman who lived on the property claimed to have “seen things” in the house but could not be induced to say more. He disappeared without a trace one day. People reported hearing the jangling of chains accompanied by other-worldly screams emanating from the attic, believed to be the tortured slaves demanding vengeance on Andrew Griffon.

Neighbors also witnessed the ghostly forlorn faces of the two soldiers looking out of the attic windows, mouthing the words to “John Brown’s Body.”

In 1936, when the building housed the lamp factory, a janitor working late on the second floor was shocked when a door burst open and a pair of boots (without legs in them) came pounding through the room accompanied by the sound of “John Brown’s Body” being belted out by a pair of unseen men. He quit his job on the spot.

That same year, the factory’s owner Isadore Seelig reported that upon arriving at the foot of the main stairs one day, a cement block flew at her from the second floor: “It didn’t fall, it was thrown. It never struck a stair as it came, and it landed just where we had been standing. My brother saw it coming and pushed me out of the way. It probably would have killed us if it had hit us.”

An immediate search of the upstairs found nothing and no one.

Years later, the factory had become a boarding house, but the terrifying events continued. A widow living on the second floor was sewing one day when she felt a drop of blood land on her arm. Then another and another. Looking up, she saw blood oozing through the ceiling from the third-floor attic…and heard the strains of “John Brown’s Body” being sung by the ghosts of the doomed soldiers.

She immediately broke her lease. When her relatives came to gather her belongings, they claimed to have seen the faces of the two soldiers through the attic window, watching them depart.

The house fell into disrepair as the 20th century passed, at one point becoming a haven for squatters who were said to have seen two tipsy men in uniform walking through the walls while singing “old timey songs.” The house continued to change hands until finally being restored to its previous grandeur.

The owner who bought and renovated the decaying house in 2004 said in a 2017 interview that he had been witness to “no drunken sailor songs, no blood dripping from the ceilings” although he did add that guests that stay in the converted attic “don’t stay too long.”

Works Consulted

Berry, Jason. City of a Million Dreams. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018

Dwyer, Jeff. Ghost Hunter’s Guide to New Orleans. Gretna, LA: Pelican Publishing, 2016

Stuart, Bonnye. Haunted New Orleans. Morris Book Publishing: Guilford, CT, 2012

Taylor, Troy. Haunted New Orleans: History & Hauntings of the Crescent City (Haunted America). Charleston, SC: History Press, 2010.

Zap, Claudine. “Ghosts Be Gone! A Formerly Haunted House in New Orleans Isn’t So Scary” Realtor.com, April 19, 2017. https://www.realtor.com/news/unique-homes/new-orleans-haunted-house-for-sale/