At a sign reading “The End of the World” in Delacroix is the beginning of Philippine heritage in New Orleans. Everyday things we might take for granted, such as raised houses over the bayous or dried shrimp in Creole recipes, began with the foundation of Asian immigrants almost 200 years ago.

When Miguel ‘Michael’ Guillera arrived in United States on the USS Kansas from the Philippines in 1909, he was one of many who enlisted in the U.S. Navy’s Great White Fleet of 16 white-painted battleships as the fleet traveled around the world from 1907-1909. The Philippines had recently become a territory of the United States after the Spanish-American War in 1898. After he left the navy he worked as a prohibition officer enforcing the Prohibition Act of 1919 and learned a lot about the sales, as well as the manufacture and transportation of alcohol. After Prohibition ended, Guillera did what may seem logical from a New Orleanian perspective, he opened a bar. The Filipino Colony Bar opened in the 1930s in the Marigny neighborhood.

But Guillera was not the first Philippine pioneer to leave his homeland and find his way to another end of the world. The first permanent Filipino-American, and possibly the first Asian-American settlement in the United States, began in the 1830s on the eastern shore of Lake Borgne, according to Guillera’s great-grandson, Randy Gonzales, Ph.D., an assistant professor of English at the University of Lafayette.

Settling in the swamp

The fishing and shrimping platform not far from the city was called San Maló in Spanish, or Saint Malo, in French. Gonzales and other members of the Philippine-Louisiana Historical Society (PLHS) will host the unveiling of a historical marker for St. Malo on November 9 at the Los Isleños Museum in St. Bernard Parish.

“We have all these stories of other peoples that lived in and settled Louisiana, but the narrative in Louisiana gets honed down,” Gonzales. “I’m in Lafayette where the narrative becomes about the French. I think that we need to be aware of all the different peoples that settled and how they did live together.”

Gonzales points out that Isleños from the Spanish Canary Islands, Croatian oyster fisherman, Frenchmen, Cajuns, and Italians lived right next to each other in the same communities in St. Bernard, Orleans, and Jefferson Parishes and that they influenced each other including intermarriage.

“That’s how Louisiana was formed, and particularly now, I think it’s important to remember that history,” Gonzales said.

San Malo literally means Saint Evil and the swampy mosquito infested wetlands on the shore of Lake Borgne were not the most hospitable places to live, but Lake Borgne was not all that different from the more than 7,000 tropical islands of Philippine archipelago.

“They were referred to as pioneers,” Gonzales said, “because no one wanted to live all the way out there and fish those areas. They knew they could easily die when a storm came. There were no hurricane warnings back then, and the storm would come up and people would disappear.”

Chef Crispin Pasia, an award-winning Filipino chef who now runs CK’s Hot Shoppe in the Central City neighborhood in New Orleans, said that typhoons, which is the Eastern Hemisphere’s name for hurricanes, come one after another and at any time of the year in the Philippines and that people have a resilient attitude after a storm.

“If it’s happened it’s happened, on to the next case, clean up the damage,” Pasia said. “Clean it up and put it back.”

After Hurricane Katrina in August 2005 when much of the city was abandoned and K-Paul’s restaurant was briefly closed, Pasia helped celebrity Chef Paul Prudhomme in feeding as many as 6,000 relief workers and members of the military.

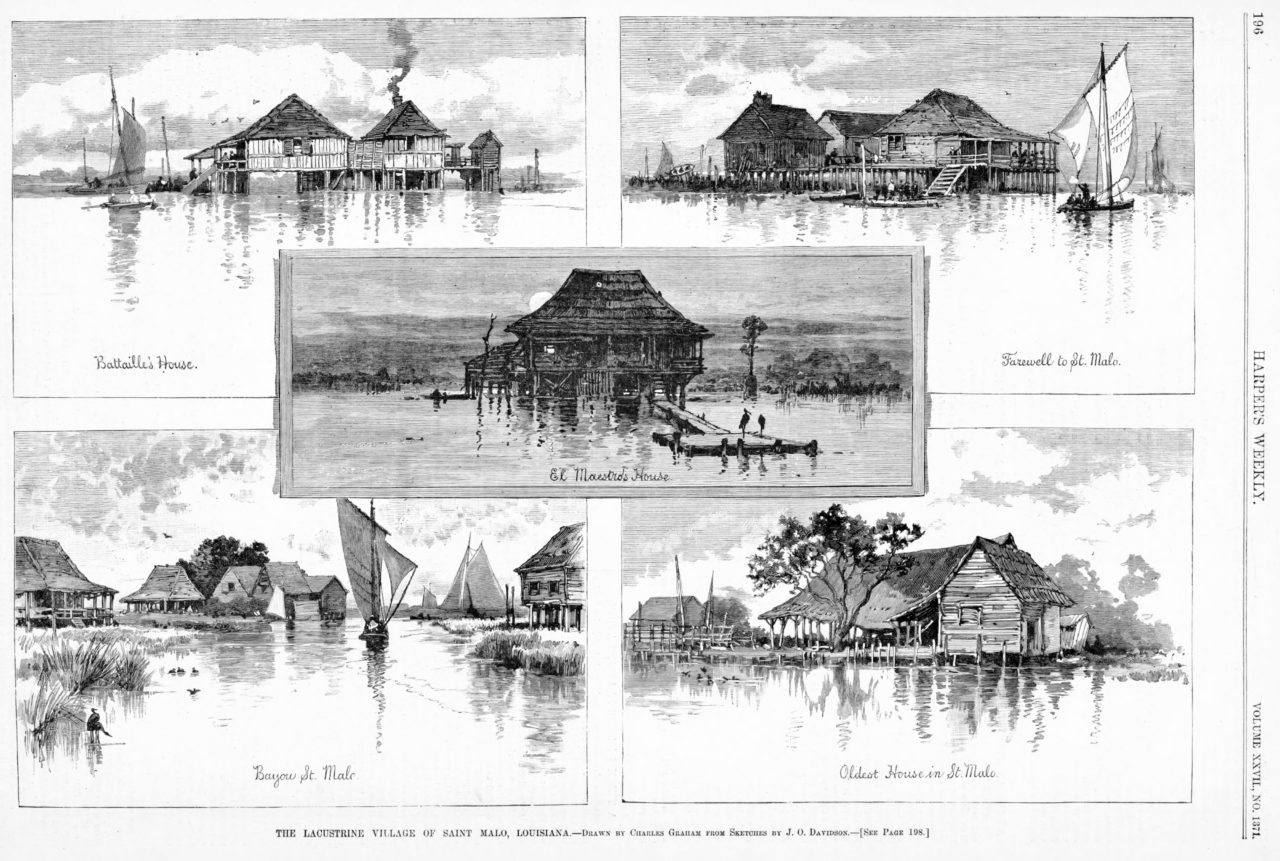

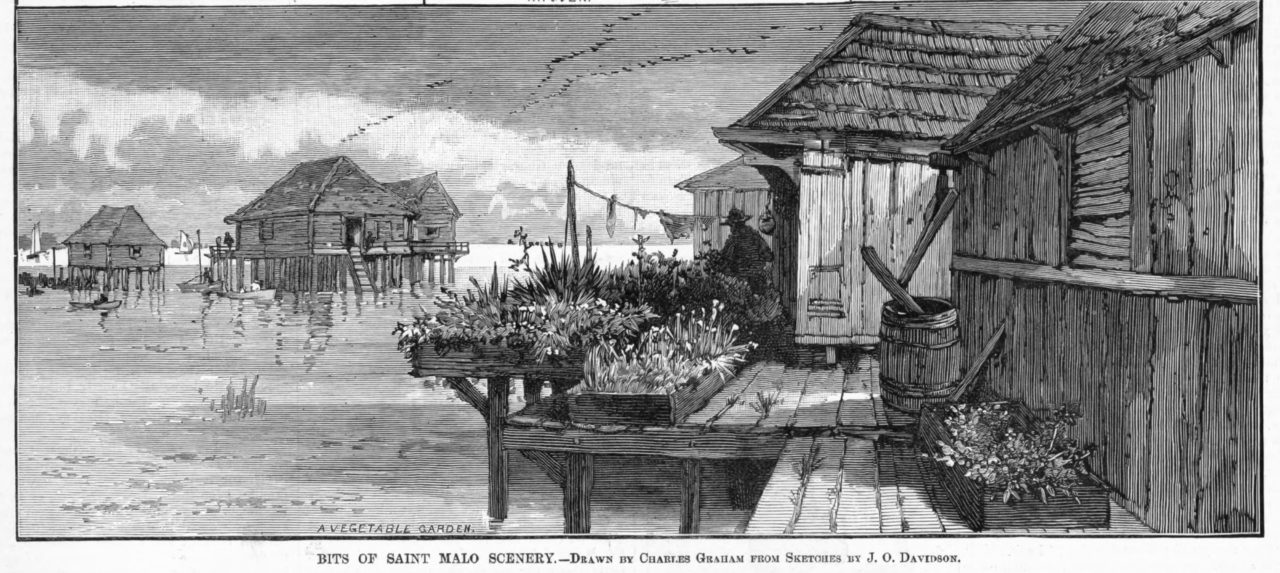

The Filipino fisherman built their village out of cypress trees on tall stilts high above the water similar to the stilted fishing villages in the Philippines that are designed to protect from sudden flooding or the change in tides. The tall stilt fishing camps were later adopted by Cajuns, Croatians, and other oystermen and fishermen around the Louisiana coast. However, the tall stilts were no match for the catastrophic Category 4 New Orleans Hurricane of 1915 (before hurricanes were named) and the village was destroyed.

Saint Malo was named after Juan San Maló who was the leader of a group of runaway slaves called cimarrones in Spanish or maroons in French. San Maló lead a rebellion of roughly 60 escaped slaves from the Spanish plantations who took up residence in the same wetlands around Lake Borgne and the Rigolets. San Malo was eventually captured by the Spanish, who controlled Louisiana at the time, and after a trial at the Cabildo in New Orleans he was sentenced to death by hanging in present day Jackson Square on June 14, 1784.

There are some legends that sailors from the Philippines were present in St. Bernard around the time of Juan San Maló but there is no written historical evidence. St. Bernard historian Bill Hyland, who helps runs the Isleños museum in St. Bernard and is an Isleños descendant, explained that Filipino sailors and indentured servants accompanied Spanish galleons to the New World after the Philippines became a colony of Spain in the 16th century. Some Filipinos may have escaped from ships possibly around the time of arrival of other Spanish speakers like the Isleños in the late 1700s while others might have lived off the coast with marooned or runaway slaves.

Filipino Pirates?

Some oral histories tell of Spanish-speaking Filipino sailors or ‘Manila Men’ that were part of pirate Jean Lafitte’s band of smugglers in Barataria Bay in Jefferson Parish. Lafitte was known to have captured Spanish galleons and other ships as part of his pirating operations. According to Gonzales an oral history claims that a Filipino was among the Baratarian privateers who joined Jean Lafitte at the Battle of New Orleans in 1815 helping Andrew Jackson’s forces defeat the British. ‘There’s a lot of legend around all of that, legend and history kind of blur together.’ Gonzales said.

Bill Hyland says the new historical marker will not include the legends and will date the Saint Malo settlement as being from the first half of the 19th century because a March 1883 article in the Harper’s Weekly Journal of Civilization explains that the settlement of Filipinos had existed for nearly fifty years at the time the article was published. Dating St. Malo to the 1830s still means that it was likely the first settlement of Asian-Americans in the United States. Today, there are over 4 million Filipino-Americans in the United States. The marker for St. Malo is the second unveiling of a Louisiana historical marker by the PLHS. The previous marker was unveiled in the town of Jean Lafitte in Jefferson Parish to mark the existence of the Filipino community called Manila Village in Barataria Bay not far from the pirate Lafitte’s old stomping grounds. Manila Village was founded later in 1800s after St. Malo and lasted until 1965 when Hurricane Betsy led to the village’s abandonment.

Hyland spoke of the importance of the historical marker and Filipinos. “What distinguishes Louisiana is its creole heritage, and I use the [French] word creole, criollo [in Spanish], and crioulo [in Portuguese].” Hyland further explained that the word ‘creole’ derives from the Latin word ‘creare’ meaning ‘to create.’ And in that context creoles created “a culture, a people, a cultural identity which evolved in Louisiana as the result of the admixture of Native Americans, Africans, Western European colonists, and Asians from the Philippine Islands. [Creole] captures that which is the essence of the Americas.”

“All of these people have been creolized but in the process of being creolized they have also contributed and redefined what constitutes a creole,” he said. “It’s very important to recognize the Filipino people as a significant element in the cultural fabric of who we are today.”

Rhonda Richoux, is a sixth-generation descendant of Felipe Madriaga, an Ilokano fisherman, originally from the Philippines who settled at St. Malo around 1849. Through Richoux’s relatives and their children, there is a 10th generation of children descended from Saint Malo settlement still living in the area.

Richoux lived in the Marigny in New Orleans and St. Bernard in a part-Filipino and part-Cajun household.

“I grew up in the Marigny neighborhood where I was surrounded by the people that I loved,” she recalled. “My Cajun family lived right across the street from my Filipino family.”

Richoux explained that when one family household would move, relatives would soon follow.

“It’s like the whole family would move to another neighborhood. It was great way to grow up.”

Richoux’s household, like the generations before, was very matriarchal because her dad, her Cajun grandfather and her Filipino grandfather worked as merchant marines or on naval vessels and were often gone for a year more out at sea. Saint Malo was inhabited mostly by men with their families living more inland.

“Gathering around food was something we had in common, both the Filipinos and the Cajuns,” she said. “When we were going to have company, we didn’t sit around and watch TV. We were in the kitchen and dining room.”

Richoux said her Cajun and Filipino grandfathers were both cooks, leading to variety of dishes during the holidays.

Dancing Shrimp

Chef Pasia came to United States to work with celebrity Chef Paul Prudhomme, a Cajun from Opelousas, who is credited with popularizing Cajun and Creole food on a national level in the 1980s with his cookbooks and K-Paul’s restaurant in the French Quarter.

Prudhomme would often gather with his employees’ families around the holidays including Pasia’s family in the Marigny.

“We’d go together with Chef Prudhomme all in the house and cook a little bit,” Pasia said.

Pasia is a culinary force in his own right. He’s been twice honored as one of the Best Chefs of Louisiana by the American Culinary Federation New Orleans, and has a way of understating himself and being humble. One can only imagine what ‘cook a little bit’ would mean at friendly family gatherings with culinary icon Chef Prudhomme with help from Chef Pasia.

Pasia said the meals could even feature leftovers of Chef Prudhomme’s famous Turducken, a deboned chicken stuffed into a deboned duck, further stuffed into a deboned turkey, a meal he said would take several hours to cook and days to prepare.

Pasia also said Chef Prudhomme would incorporate ingredients created by the Filipinos, including dried shrimp as an ingredient in Prudhomme’s Shrimp Creole recipe. Dried shrimp was also used in other sauces and added to flavor gumbo.

Before refrigeration, the traditional Filipino method of drying shrimp was one of the only ways to preserve shrimp. According to Winston Ho at the University of New Orleans history department, fisherman would bring shrimp to the processors at places like St. Malo and Manila Village where the shrimp was boiled in salt and brine. The shrimp was then spread out two to three inches deep on the drying platforms. After three days, teams of workers removed the shells by walking over the shrimp in a shuffling circle pattern known as the “shrimp dance.”

Pasia said another dish called “Dancing Shrimp” was occasionally on the menu at K-Paul’s as a nod to the shrimp drying process by Filipinos as well as Chinese fishermen in Louisiana.

This is a photograph of the drying platform at Manila Village before the Hurricane of 1915. The painter Frank Schoonover said this platform was up to 200 feet square or two football fields in area.

Dried shrimp was exported around the world and helped popularize shrimp beyond coastal cities. Before improvements in shrimp farming in the 1980s, fresh shrimp was not readily available and expensive in cities inland.

After Hurricane Betsy the storm damage was not the only reason the Filipinos didn’t rebuild the Manila Village shrimping platform. The communities along the coast had been dwindling because of technological advances in the shrimping industry, including refrigeration and machines to remove the shells from shrimp. Large platforms to dry out shrimp and fish along the bayous and lakes were no longer needed, as a lot of the shrimp manufacturing moved more inland. Coastal erosion, subsidence, and wetland loss caused by increased offshore oil production and the altering of the Mississippi River flow with dams and control structures were also beginning to take their toll on the coast.

Even before Hurricane Betsy, Barataria Bay where Manila Village was located, had already lost nearly 100 square miles of land by 1956 or the equivalent of half the land in the city of New Orleans according to the United States Geological Survey. Barataria Bay lost over 400 square miles from 1932 to 2016. In the 1800s, Lake Borgne where St. Malo was located was considered a true lake and a separate body of water with wetlands protecting it from the Gulf of Mexico. But now, with so much land loss, Borgne is considered a lagoon connected to the Gulf. Lake Borgne borders Orleans Parish on its western and northern shores and St. Bernard Parish on its southern and eastern shores.

“Asians have been here a very, very long time…”

Though most of her family now lives inland, Richoux’s still recalls how her ancestors got around using pirogues or canoes carved out of cypress tree logs. Pirogues in French, or piragua in Spanish, refer to native boats in formerly European-colonized areas including pirogues made by Cajuns, Jean Lafitte’s Baratarians, and Filipinos. The annual World Championship Pirogue Races take place today in the town of Jean Lafitte near where Manila Village once stood.

Filipinos also took part in Carnival and Mardi Gras balls and crowned Queens, including Richoux’s ancestors at the Filipino-American Goodwill Society, or “The Flip Club,” in the Marigny. Gonzales said that the Filipino organization Caballeros de Dimas-Alang in New Orleans had a Mardi Gras float that was awarded the prize for best decorations in the Elks Krewe of Orleanians’ first Mardi Gras parade in 1935.

Richoux spoke about her Filipino roots and why it is important to remember the Asian influence in Louisiana and the country.

“Even after all of these centuries and waves of immigration, the country’s history is still so white-centric,” she said. “I know that sounds political but it’s ridiculous. [People think] we don’t go any further back than the 1960s. Asians have been here a very, very long time and it’s like we’re not part of the conversation. Our families have been here a long time and we are part of the fabric of the country.”