The Donora Smog Museum: a single-room snapshot of air quality in western Pennsylvania

Mark Pawelec, a Donora Smog Museum volunteer, remembers a family who visited the museum all the way from England. After visiting family in Michigan, they were looking for a place in the United States to visit.

“Their one stop, of all places, they’ve never been to Pittsburgh, they stop at Donora to learn about the smog,” Pawelec said. “They’re telling me stuff about the London smog, because the guy was old enough to be part of the London smog.”

Though the museum is most well-known in the local Mon Valley area, its extensive documentation of the small Washington County borough’s history of pollution resonates with people around the world.

Donora suffered a widely reported onslaught of smog in October 1948 that killed 20 people and made thousands more sick. While this harrowing incident plagues the history of the small, Rust Belt borough, it’s often referenced as one of the impetuses for the clear air movement.

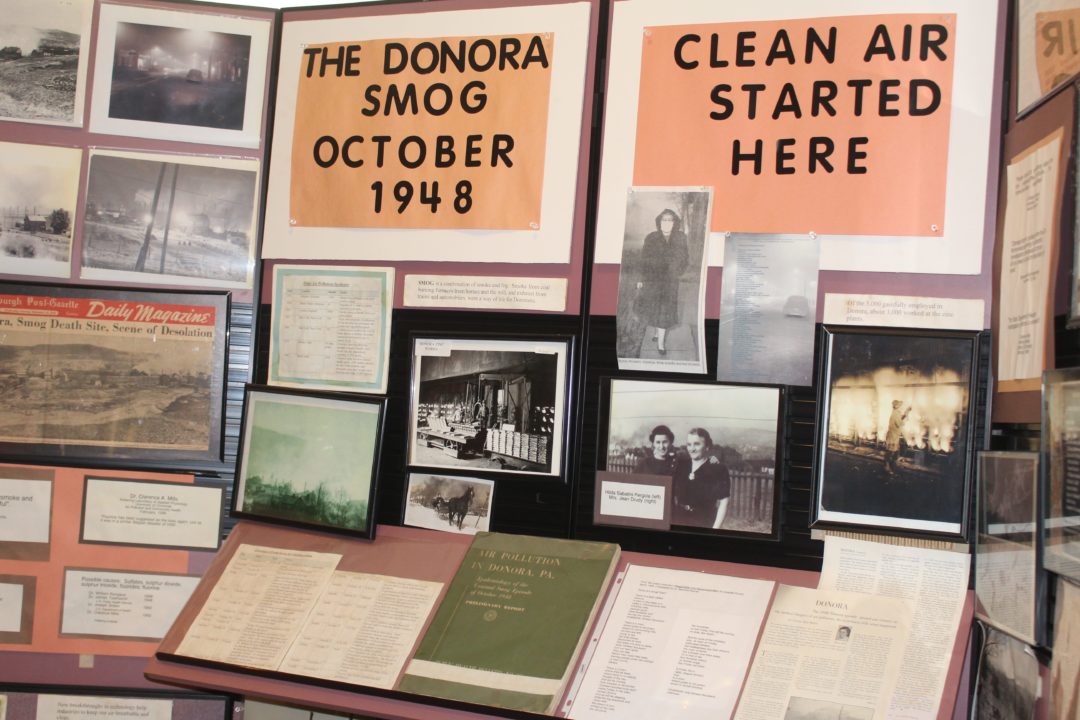

Therefore, while there are plenty of discomforting records of the disaster at the Donora Smog Museum, there are also mementos and messaging that point toward a better future, thanks to a lesson learned. The motto, of sorts, for the museum puts forth an optimistic perspective: “Clear air started here.”

It’s not even all about smog history at the museum – volunteers also display a lot of other remnants of Donora’s storied past, which most prominently includes sports.

Documenting the Smog

While the Donora Smog Museum only takes up a single, modestly sized room, you can lose hours reading preserved newspaper clips and other documents. The museum ends up giving an accidental history lesson on the drastically changed local print media market. On display are several long-defunct newspapers, like The Charleroi Mail and The Donora American, with alarming articles about the smog.

There are also a ton of decades-old photographs, capturing people and locations related to the smog incident. A series of photos of Donora Zinc Works, one of the main mills operating at the time, is on display.

Students, whether they attend local middle or high schools or colleges from around the school, use the museum as a valuable resource. Fulbright Scholars from China and Japan even visit the museum to learn, according to Pawelec. Many of the images and documents are provided to students digitally, like on flash drives, as well.

“They don’t even necessarily have to visit here to get an enormous amount of research material,” Pawelec said.

Much of the smog history paints a miserable picture, but the education largely offers a benefit.

“We can’t change the history,” Pawelec said. “We can help educate people, and I think we do a good job of that.”

Stan the Man

One day, two brothers in their 30s wearing St. Louis Cardinals T-shirts asked the volunteers at the Smog Museum if it was open. It was, so the brothers grabbed their parents and entered. They made a stop in Donora after visiting the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum in Cooperstown, New York, because they wanted some extra information on Stan “The Man” Musial, a beloved baseball player born and raised in Donora.

After showing the family around, the volunteers made an offer. The museum wasn’t busy, so if they wanted, they could hop in a car and take a look around Donora to see where Musial went to school and attended church. They agreed.

“No matter where we stopped… they’re taking each other’s pictures,” Pawelec said.

Pawelec heard a ringing endorsement from the family – that their experience in Donora was even better than Cooperstown.

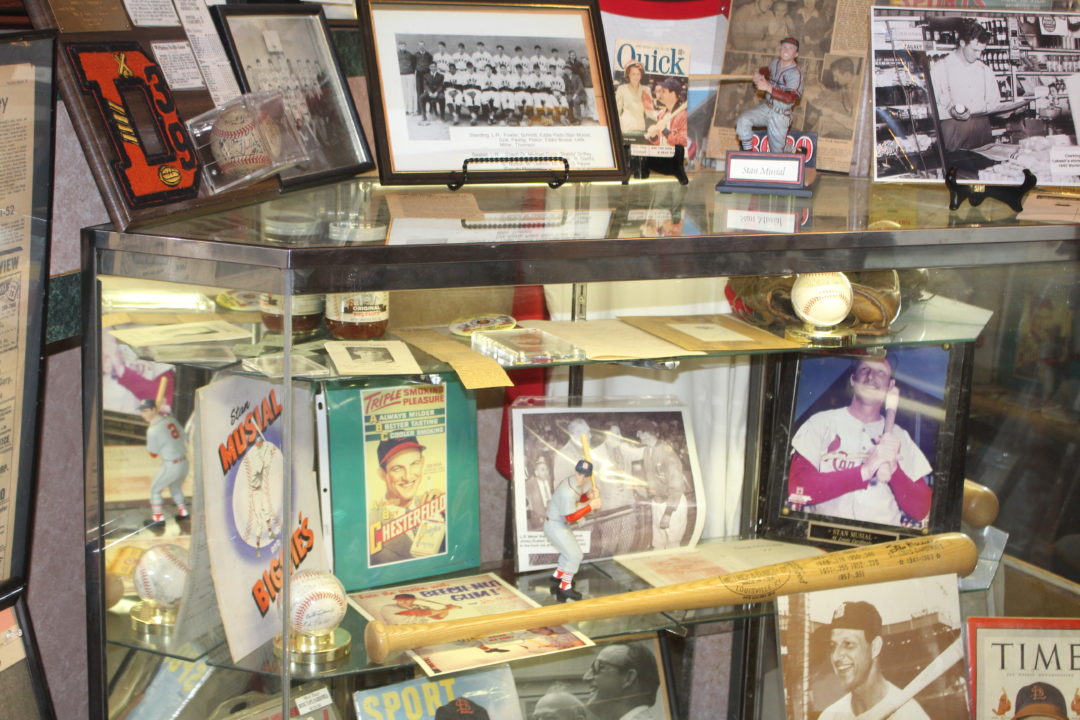

While it doesn’t demand the same amount of attention as the smog history, the Musial section at the museum certainly shines. There are old newspaper clips, baseball cards and other various Musial knickknacks and oddities on display, including a container of “Stan the Man” Original BBQ Sauce donated to the museum by a St. Louis native who was living in Alaska when he visited the museum.

“That sauce went from St. Louis to Alaska, from Alaska to Donora,” Pawelec said.

Visitors like that family floored by the real-life stomping grounds for Musial underscore the magic of the small borough hidden from its most cynical residents.

“Donora’s a rundown steel town. We can’t deny that,” Pawelec said. “But, what we take for granted, people from Donora… when you bring in these outside visitors, they don’t see it that way.”

Odds and Ends

After Pawelec had thoroughly showed me the museum’s dense displayed collection, I asked if there’s any interest in eventually getting a bigger space.

“This is the tip of the iceberg,” he said, referring to the room with all of the materials on display. He started to walk me toward the back, which has drawers upon drawers filled with blueprints and maps along with lots of other items. “This is the stuff that isn’t on display.”

He showed me some old basketball jerseys used by student athletes at Ringgold High School, the then and current high school for Donora kids. Ringgold High School happens to be my alma mater – I even grew up in Donora and lived there until I moved a short distance within the same school district when I was in middle school.

Somehow, I managed to never visit this museum until I attended it for this story. I learned quite a bit about the area on my trip, and Pawelec’s comments about the borough’s significance genuinely moved me. As I walked around the museum’s massive collection, surrounded by remnants of my hometown’s storied history, I felt good.

“Would we like to be in a bigger space one day?” Pawelec said, repeating my question back to me. “Yes.”