On Oct. 15, 1890, New Orleans Chief of Police David Hennessy Jr. was assassinated by shotgun while walking home near Basin Street. His death created a black hole of vigilante violence and political power struggles. But who was Hennessy before his death became a footnote to history? To understand that, one has to understand the social and familial influences Hennessy Jr. grew up under.

Vice in the Big Easy

After nearly a century of increasingly large waves of immigration, the city was a cauldron of political and ethnic conflicts ready to explode. In the mid-to-late 1800s, New Orleans was host to numerous thugs, gamblers, prostitutes, con men, and madams. Instead of acknowledging that these kinds of vices had always plagued the city, partly because of France’s policy to release criminals from its prisons to send to the Louisiana colony, it was far easier to blame the growing criminal class on whatever immigrants happened to be disembarking at the Port of New Orleans that year.

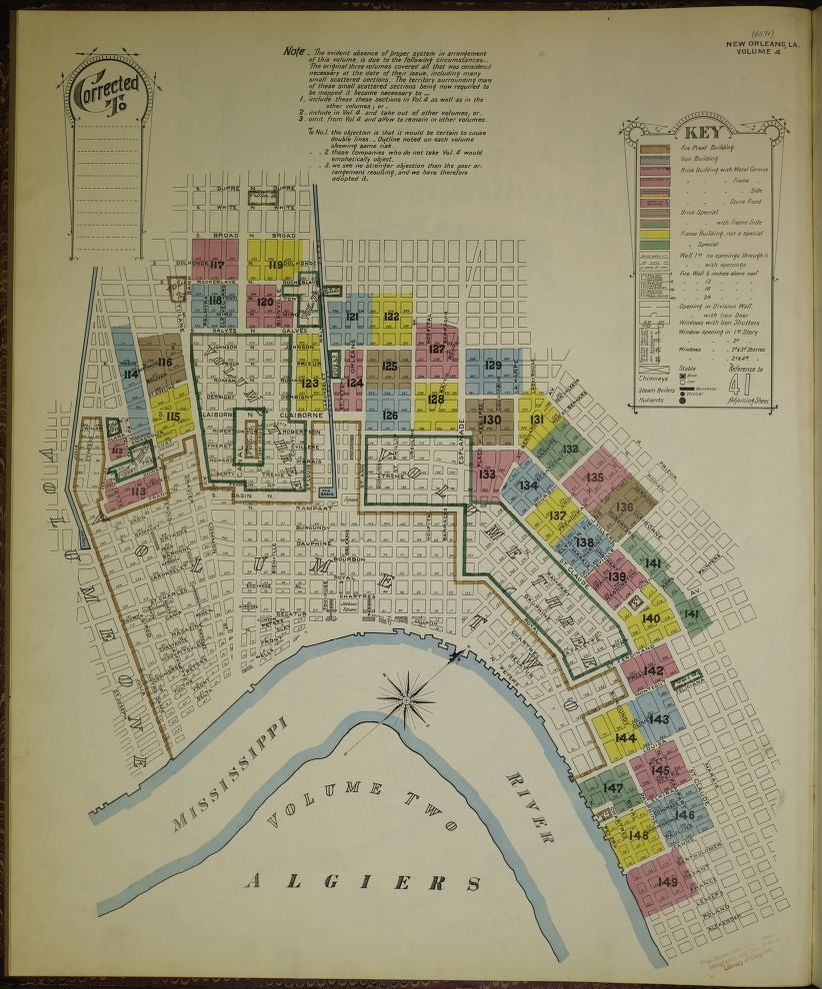

Girod Street, today found in the Central Business District, at the time, was a particuarly rough area with many makeshift brothels, “grog” shops, and a high crime rate. It was in these conditions that the poor found themselves living in poorly constructed, tightly packed together shanties, and it was in this environment that Irish immigrant David Hennessy Sr. arrived in the 1830s. But instead of lamenting the conditions of his new Girod St. address, he embraced them.

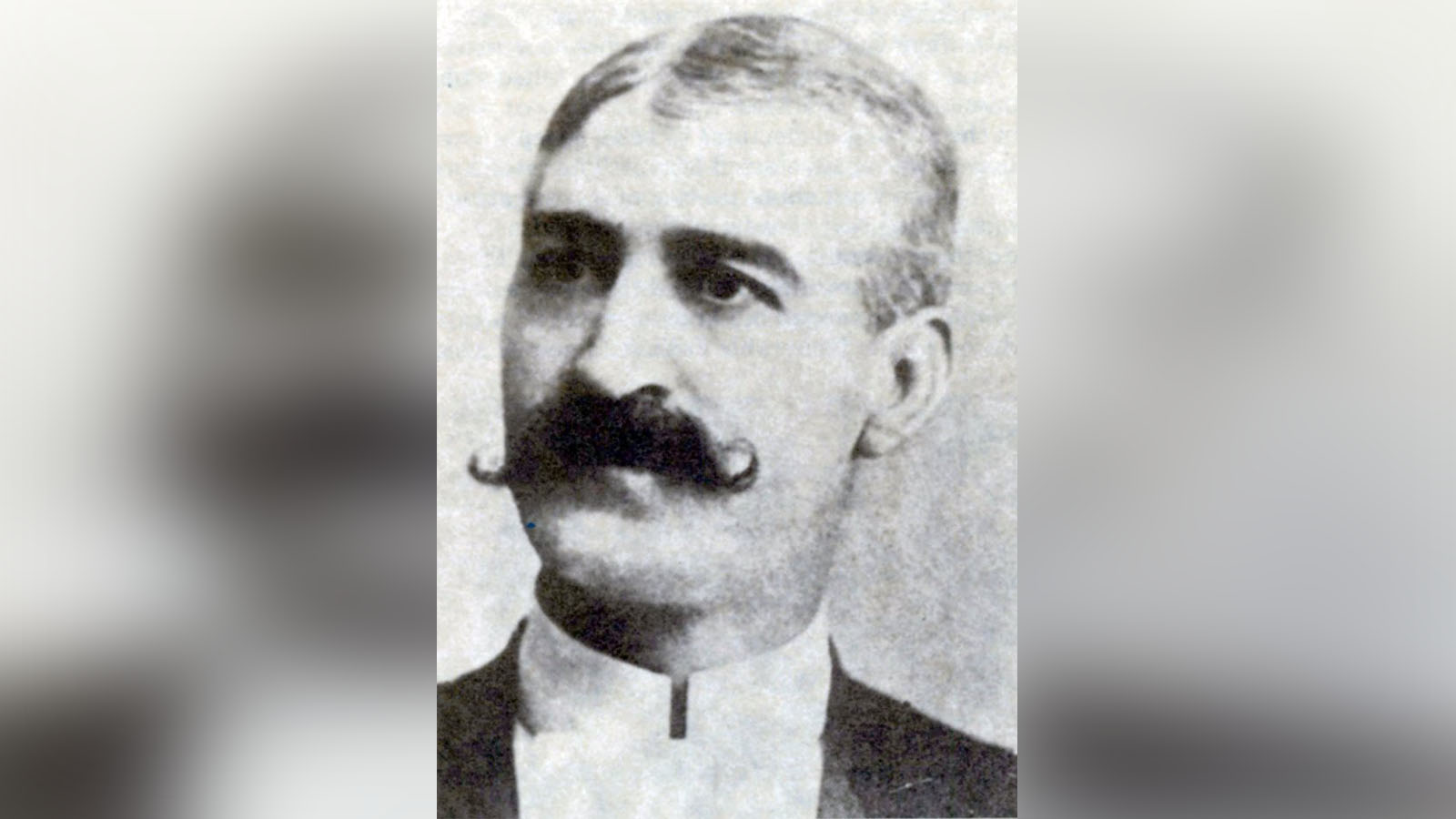

David Hennessy Sr.

Hennessy Sr. arrived in a New Orleans still more swamp than city. His first wife died in a yellow fever epidemic, and he didn’t remarry until 1854 when he met fellow Irish immigrant Margaret Finn. David Jr. was born in 1858, just as the Civil War was threatening to begin. Hennessy Sr. served as a cavalry officer in Union-occupied New Orleans.

MORE READING: Stories of the New Orleans mafia as told by Cajun Ganster Frency Brouilette

His brother was killed during the war and, to receive the deceased Hennessy’s Army benefits, Hennessy Sr. lied about being the only living kin to the dead man. In reality, his brother had a wife and at least one child in Ireland. This fraud was discovered, and Hennessy Sr. was brought to trial for perjury. He was cleared of the charges, not because they weren’t true, but because several character witnesses testified to Hennessy Sr.’s bravery in the war. Emboldened by this victory, he took a job as a police officer in the newly formed Metropolitan Police Force. The position did nothing to Hennessy Sr.’s character except make it worse.

What follows is a brief timeline of some of the major events in Hennessy Sr.’s time on the force:

March 9, 1866 – At 101 St. Charles (which today is a Starbucks), Hennessy Sr. allegedly took part in a murder along with three other men. All four were cleared of the charges despite the stabbed man identifying his attackers before he died.

Aug. 24, 1868 – Hennessy Sr. was arrested for assault and battery after attempting to bribe a politician with $1000 to introduce a bill which the other man refused to do. This led to a physical assault which left both men much the worse for wear.

Dec. 16, 1868 – Hennessy Sr. arrested three thieves who’d been using an abandoned house as a headquarters. The officers with him took all the goods stored in the house, most of which were conveniently never checked into evidence.

Dec. 24, 1868 – Hennesy Sr.’s house caught fire. He was able to put out the blaze before anyone was hurt or the house was past repair. He believed one of the thieves or their accomplices had tried to kill him and his family.

Feb. 26, 1869 – Inside the 8th District Court Coffeehouse, shots were fired. Hennessy Sr. was found on the floor with three wounds to the abdomen. A doctor was found in the area to examine the still alive Sr. and, while doing so, found a pistol hidden in both front pants pockets, a pocket knife, and a pistol in his waistband. It was also well known that Sr. carried a sword cane. Whether or not that was found at the scene is a point of contention.

A door was taken off its hinges to move the now dead Sr. to the coffeehouses’ courtyard. There the doctor discovered two of the three shots were fatal with one having torn through the sac around his heart and another piercing his intestines. These wounds would eerily mirror his son’s in a mere 20 years’ time.

Like Father, Like Son

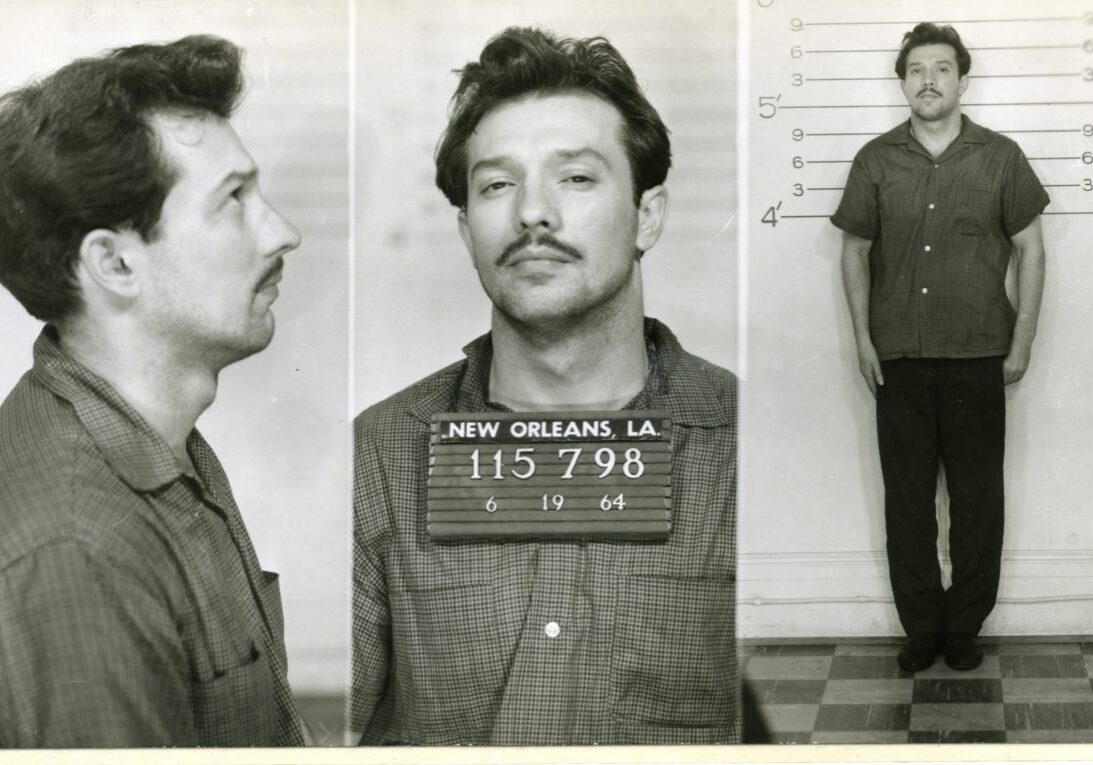

After his father’s death, Hennessy Jr. and his mother struggled to survive on the meager pension paid to widows of the police force. Luckily, Hennessy Sr.’s former cavalry commander was appointed head of the Metropolitan Police, and the man took pity on the younger Hennessy by giving him his first job as a messenger boy for the force. Hennessy Jr. took to police work much like his father before him, and, at the age of 17, officially joined the force as a patrolman. A year later, Jr. single-handedly caught two men committing burglary and brought them into the station after having beaten them severely. He made detective by his 21st birthday.

In a far more impressive feat, Hennessy Jr. caught a Sicilian fugitive from justice who’d been hiding in New Orleans. Esposito, a known kidnapper, was sent back to Italy where he was sentenced to life imprisonment for having cut off a British tourist’s ear in a ransom plot. Hennessy Jr.’s capture of Esposito made national headlines and cemented his public image as a hometown hero.

However, to capture Esposito, Hennessy Jr. declined to inform his superior, Thomas Deveraux, who charged him with abandoning his post. As Jr. and Deveraux were competing for the position of chief of police, it made sense Jr. hadn’t wanted Deveraux to be part of the sting, but it also made sense that Deveraux would want to show his power as Jr.’s superior on the force. This clash of ambitions led to Hennessy Jr. killing Deveraux in what would be ruled as self-defense. Not everyone agreed with the verdict, and a New Orleans State editorial called him a murderer outright. The resulting controversy caused Jr. to resign from the Metropolitan Police Force in April 1882 in disgrace.

In 1888, Mayor Joseph A. Shakespeare appointed Hennessy Jr. to the chief of police position he’d so coveted. But, ambitious as ever, Jr. never stopped his less respectable enterprises. In February 1889, it was reported Jr. was involved in a protection racket for various vice activities including some of the most notorious brothels in the Storyville area. Involved in a less defined way with the Red Light Social Club brothel were Joseph and Peter Provenzano.

Hennessy Jr. was set to testify for his friends, the Prozenzanos, against the Matranga family in what was essentially a turf war scuffle, but was shot two days before the trial began.

Rumors began to swirl that Mafiosi had been responsible for the chief’s death, but in reality, Jr. had enemies from the criminal world and the political one. Part of his being appointed to the chief position was the agreement he’d consolidate the police force. This caused many to lose their jobs and made him no friends at the station. With his illicit activities and the fact he still lived in the crime-filled Girod Street neighborhood, this meant nearly anyone could have been responsible for his assassination. But, as usual, it was easier to blame the Sicilian immigrants for the shooting, and soon it was accepted as fact the Mafia had been the ones to order the hit on Hennessy Jr.

MORE: The Beginnings of America’s Mafia in New Orleans

Aftermath of a Police Chief’s Death

Despite the controversies surrounding him in life and death, Hennessy Jr. was enormously popular among the people of New Orleans. His funeral was attended by most of the city’s citizens. Unfortunately, that wasn’t the end of the story.

In the weeks after his assassination, more and more Italian men were arrested, questioned, and released until 9 of the 19 men accused were taken to court to stand trial for Hennessy’s murder. All of the men were to be released after a mistrial was declared for three, and six were found not guilty, a fact which enraged the populace and created a vigilante need for justice.

What followed next was the worst mass lynching in United States history. On March 14, 1891, a crowd of 6000 – 8000 people gathered at the Henry Clay statue which stood at the intersection of Royal and St. Charles in Canal Street’s neutral ground. After a series of speeches to rile the mob, they marched on the Parish Prison located in the Treme on Marais Street. When the vigilantes arrived, they broke through the gates with a makeshift battering ram and stormed the prison.

Once inside, they searched until they found some of the men in a stairwell. The mob shot the men over 100 times before dragging the rest outside where they were hung from lamp posts. All told 11 of the 19 accused men were hung or shot with not one guard or police officer attempting to defend them. No one was punished for the lynchings.

References

For more in-depth information on the Hennessys and the tragedies surrounding them, refer to the sources below.

- “Before Storyville: Vice Districts in Antebellum New Orleans, Part 1.” Richard Campanella. Tulane School of Architecture. Preservation in Print, September 2015. https://richcampanella.com/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/article_Campanella_Preservation-in-Print_2015_September-Before-Storyville.pdf

- The Brackish Podcast. Mix it Up a Little. “S01 E17 – TBP Episode 17~David Hennessy Sr. The Irish Brawler and Gunslinger.” April 7, 2020. https://rss.com/podcasts/brackish/33427/

- Paddy Whacked: The Untold Story of the Irish American Gangster. T.J. English. HarperCollins E-books, 2007. https://silo.pub/paddy-whacked-the-untold-story-of-the-irish-american-gangster.html

- “Sicilian Lynchings in New Orleans.” Justin A. Nystrom. 64 Parishes. June 24, 2013. https://64parishes.org/entry/sicilian-lynchings-in-new-orleans

- “Who Killa da Chief?’ Revisited: The Hennessy Assassination and Its Aftermath, 1890-1991.” John V. Baiamonte, Jr. Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association, Vol. 33, No. 2 (Spring, 1992), pp. 117-146 (30 pages). https://www.jstor.org/stable/4232935