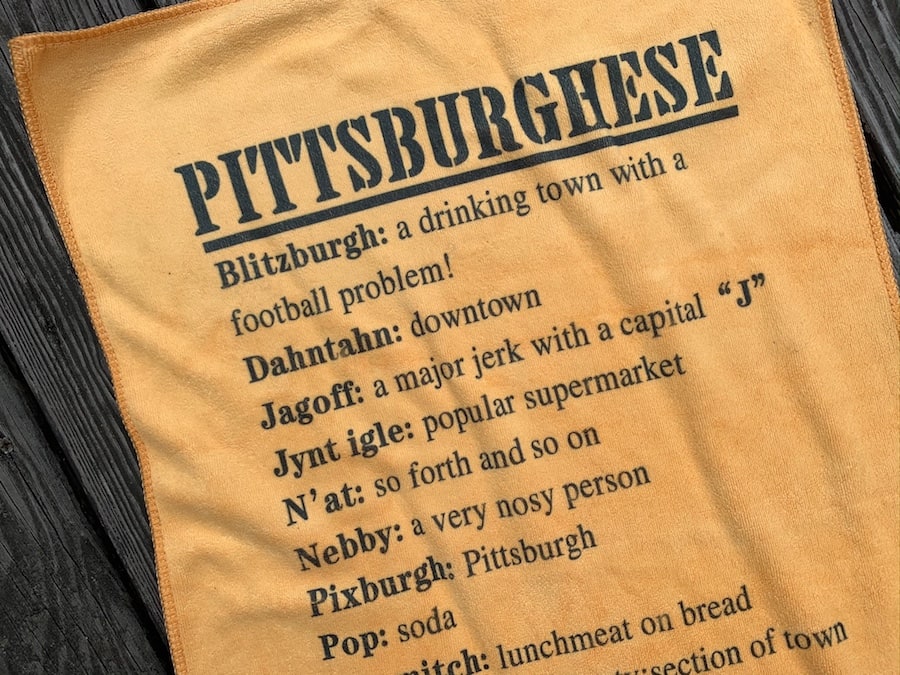

“Gumband,” “jumbo,” “dahntahn”–for newcomers to the Pittsburgh area, listening to local chatter might feel like entering a new country. But for those in the know, the local slang, or “Pittsburghese,” is a way of life.

What’s more, it doesn’t take long to realize locals hold Pittsburghese in high esteem, a trait Professor of Linguistics and Rhetoric at Carnegie Mellon University Barbara Johnstone couldn’t help but notice when she moved to the area in the late ‘90s.

Did you know that you can watch Very Pittsburgh shows on your TV?

📺

Grab the Very Local channel on Roku, Amazon Fire and Apple TV to watch all of our shows for FREE.

Johnstone wrote the book on it literally, and in her research, she’s found that prized local lingo, what many call Pittsburghese, is more about the way locals think they talk than how they actually speak. What drew Johnstone to study Pittsburghese wasn’t the language itself, but the local obsession and pride Pittsburghers take in it.

To understand the local fixation on speech, language, and history, you have to trace Pittsburgh’s speech back to its origins.

Beginnings of Pittsburgh speech

The origins of the local dialect, what Johnstone calls Pittsburgh speech (notably not Pittsburghese) in her research, can be traced back to the first English-speaking immigrants to settle in the area. While Germans and Quakers claimed eastern Pennsylvania, the Scots-Irish ended up in the southwest in the late 17th century, early 18th century.

Scots-Irish were doubly immigrants. They were Scots who moved to Northern Ireland at the beginning of the 17th century, then found their way to Pittsburgh. These immigrants spoke a Scottish dialect of English, explains Johnstone. Pittsburgh speech has the Scots-Irish to thank for aspects of the regional accent, as well as cornerstone vocab such as “nebby,” “slippy,” “redd up,” and yes, “yinz.” Similar to y’all, yinz is a sort of contraction of the Scots-Irish “you’uns,” which eventually transformed into yinz.

As more Europeans immigrated to southwestern Pennsylvania, they picked up the regional dialect. “A young person growing up anywhere, they don’t want to sound like their parents,” says Johnstone, “They would pick up the words, phrases, and pronunciations that the locals used.”

Though its base was in Scots-Irish, the language continued to evolve as the region changed. Germans, Polish, and Eastern European immigrants arriving in the 19th and 20th centuries added their own flair to the local speech, adding vocabulary (and classic foods) like salami, pierogi, and halushky to regional dialect.

In her research, Johnstone also theorizes that Eastern European immigrants in the Pittsburgh region might be responsible for the now all-too-familiar pronunciation of downtown as “dahntahn.” “They might’ve found it easier to say ‘aw’ over ‘ah.’”

And what about the classic vocabulary like jumbo, chipped ham, and pronouncing Giant Eagle “Giant Iggle”? Clever marketing, explains Johnstone. Jumbo and chipped ham came from Isaly’s, a local manufacturer that still produces dairy and deli meats today. And “Iggle” came from the big bird, Giant Eagle, itself in a marketing campaign.

The Fall of Steel, and the Rise of Yinz

A quick trip down to the Strip reveals tables of black and gold Pittsburghese souvenirs. Shirts, shot glasses, and souvenir coffee mugs are etched with regional phrases and local in-jokes. Pittsburgh Dad has made a career parodying the way locals speak, and Pittsburghese comes up frequently on late-night talk shows. Nowadays, it’s not uncommon for new parents to be gifted a “jagoff” onesie for their newborn. There’s pride, and a touch of teasing, that settles around what many call Pittsburghese.

This pride around “Pittsburghese,” or the speech specific to the area, really began during the ‘70s and ‘80s during the fall of the steel industry, says Johnstone. During this time, the obsession around Pittsburghese really took off.

With the collapse of the steel industry came the collapse of the local economy. Young people no longer had the option of becoming steelworkers, a career their parents and their parent’s parents took on with pride. It was a huge part of local identity, says Johnstone, and when the economy went south, many people had to leave the city to seek work.

The city had a bit of an identity crisis; what could transplants hold on to from their hometown?

“As people move away, they’re nostalgic for people who sound like home. This generation of Pittsburghers built their identity around speech,” Johnstone explains. That, and the Steelers, who were a successful icon of the city in a time when little else was. This generation of Pittsburghers couldn’t identify with the steel jobs of their parents, so they latched onto the Pittsburgh accent and regional vocabulary as a point of pride and camaraderie.

Pittsburghese, in some ways, was born out of Pittsburgh’s collapse and born outside of Pittsburgh. It was a reminder of home and a character quirk that drew pride for those who had little choice but to leave the city. This sort of diaspora and pride of Pittsburghese brought it into the national consciousness, as Pittsburghers spread across the country to find work and coworkers asked about their “Pittsburghese accent.”

Pittsburghese today

Pittsburgh speech, as it once was, is much harder to find nowadays, admits Johnstone. People move around now more than they ever used to, and there’s an argument that people will all start to talk the same as we become more mobile.

But, Pittsburghese has a pride associated with it that’s not always found among other regional dialects, and Johnstone finds that many people who move to Pittsburgh want to adopt local slang. You’ll also find that many Pittsburghers who left in the ‘70s and ‘80s have returned, bringing the Pittsburghese pride back with them.

While they may not have the accent or the steelworker upbringing, aspects of Pittsburghese live on. “It doesn’t sound like how your grandparents talked,” says Johnstone, “but young people moving here also want to use Pittsburghese to show some kind of local identity.”

But like any form of local dialect, Pittsburgh speech will evolve. In recent decades, the area has seen an influx of former Soviet Union immigrants, Southeast Asia, and the growth of the Latino population just south of the city. Like the immigrants who came before them, these new Pittsburghers will contribute new words and pronunciations to evolving Pittsburghese.

Buy Barbara Johnstone’s book about Pittsburghese

Barbara Johnstone’s book is available from these booksellers:

- Amazon – Kindle, Hardcover, Paperback

- Bookshop.org (profits go to local booksellers)

- Better World Books

- Biblio

- Ebay