Much has been written about the meeting of Jenny Lind, the world’s most famous opera singer, and Madame de Pontalba, the richest woman in New Orleans. In 1851, the two met at the Pontalba Buildings, which flank Jackson Square, as Lind stopped in the city for 13 performances during her two-year concert tour of America. The women couldn’t have seemed more different to the casual observer.

Lind had risen from impoverished circumstances to become one of the most famous people in the world, whereas de Pontalba had been born into wealth. Those who never looked further than that first glance missed striking and surprising similarities between the women. To fully understand the significance of their meeting, the world they were born into, as well as their own stories, must be examined.

READ MORE: Top 5-04: The Five Most Influential Women in New Orleans History

A Woman’s World in the 19th Century

“Respectable women must be contained.”– Marise Bachand

This was a hard and fast rule for much of recorded history. From the feet binding of Tang Dynasty China to English ladies routinely wearing dresses weighing up to 90 pounds, women have been constrained in many ways. Jenny Lind and the Baroness Micaela Almonester de Pontalba were well aware of this fact. Both were born in a time when feminine persons could not vote, own land in most circumstances, and often could not choose their spouse.

In this time period, the ideal lady was submissive and sedentary. Even to be too often outside was considered vulgar as only lower class and ‘working’ women belonged on the streets. Men were allowed to confine their wives should the woman be disobedient, a term encompassing everything from not being able to bear children to voicing an unwanted opinion. Women wearing pants could be prosecuted as only dresses were acceptable ladies’ wear. Partly because of this, women rode in carriages while men rode on horseback.

One thing respectable women could do openly was head charitable organizations or at least do charity work. As it happened, both Lind and de Pontalba were able to parlay charitable pursuits, with the accompanying money, into unprecedented social mobility while (mostly) retaining respectability.

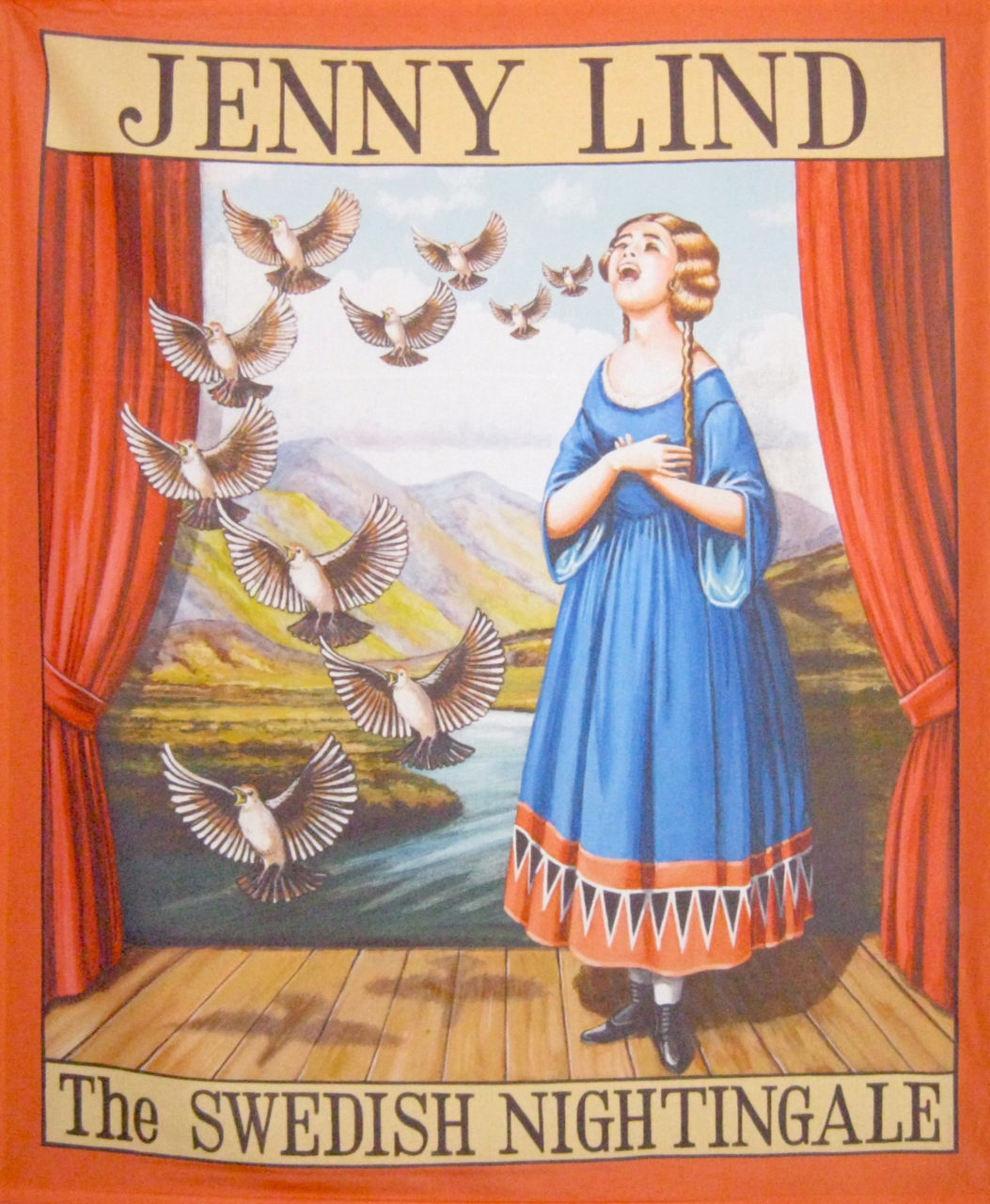

Jenny Lind – The Swedish Nightingale

Born in 1820 in a poor area of Stockholm, Sweden, the illegitimate daughter of Niclas Lind, a bookkeeper, and Anna Marie Fellborg, a schoolmistress, Jenny Lind’s birth was not celebrated. She was the second daughter to a single mother who, upon discovering she was pregnant with Jenny, concealed the pregnancy, gave birth in secret, and sent the baby to live with her cousin 15 miles away.

The stay was short-lived. A fight with her cousin saw Jenny returned to her mother’s unhappy home at the age of 4 where she was primarily raised by her grandmother. By chance, a dancer from the Royal Opera House heard her singing and brought her to the Theatre School to sing for the director. After a stunning audition, she became, at 10 years old, the youngest person ever admitted into the Swedish Royal Theatre School. Her trills and high notes were so clear she was nicknamed The Nightingale, but while Jenny found joy in music, her home life continued to deteriorate.

Her mother had turned their home into a boarding house, but the place wasn’t fit for human life. When Jenny’s squalid living conditions with her mother were discovered, she was allowed to live at the school. However, when Lind and Fellborg married in 1835, they successfully sued to have Jenny returned to them. The arrangement lasted four years until Jenny, now an adult, asserted her theater salary could no longer be spent by her mother but would instead be donated to charity as she believed her voice to be a gift from God. This led to a rage on her mother’s part, and in 1839, Jenny moved out permanently.

Though met with unparalleled success in the opera world, the effects of Jenny’s childhood never entirely faded. She suffered from deep melancholy, what today is called depression, and anxiety over letting the people counting on her down. These fears caused her to retire twice from the stage and attempt a quieter life.

During one of her breaks from singing, she nearly entered what would assuredly have been a bad marriage. The young man asking her to be his bride demanded all her earnings and insisted she obey Biblical law so she would be utterly submissive to him. Friends rescued her from the man after he began asserting he’d “die of heartbreak” if she left. Remarkably, he did not keel over dead when she ended the engagement.

Lind was lauded as the greatest soprano of the time, and P.T. Barnum saw a chance at finally gaining the respectability he craved. If he could bring The Nightingale herself to America, his reputation as a huckster might not be forgotten, but it would certainly fade a bit. Leary of that same reputation, Jenny demanded her salary for the tour upfront, something Barnum had not counted on. Still, he managed to raise the $187,000, nearly $6 million today, and Jenny reserved the money to fund free schools in her native Sweden.

READ MORE: Ain’t Dere No More: Canal Street’s Dime A Dozen Store

She arrived in America in September 1850 to begin a lengthy two-year concert tour where she performed 135 concerts in 21 months. While touring, she fell in love and married her friend and accompanist, Otto Goldschmidt. The couple returned to Europe in 1852, had three children, and Jenny continued to sing until 1883 in ever rarer performances.

Jenny Lind died at her home in England from cancer complicated by a stroke.

Baroness Michela Almonester de Pontalba – The Iron Flower

Born in 1795 to Louise de la Ronde Almonester, 37, and Don Andres Almonaster, 67, Micaela Almonester barely knew her father who died when she was 2 years old. The elderly man had prepared for this, however, and had provided generously for his daughter in his will. While he almost certainly must have known this would make his daughter good marriage material, he couldn’t have anticipated his fortune would very nearly kill her.

At 15 years old, Micaela and her 20-year-old cousin, Celestin, met and married within three weeks. The ceremony for their arranged marriage took place in St. Louis Cathedral on Oct. 23, 1811. It was July 1812 before Micaela and her new husband reached France. They were to live at his family’s country estate, the chateau Mont-l’Eveque, 50 miles from Paris.

Micaela fell pregnant soon after arriving at the chateau and gave birth to what was to be the first of five children. To liven up the countryside, she put on plays with full costumes and actors from Paris for her, and the children’s, amusement. It was a good start to married life.

This, however, was before her father-in-law, the Baron Joseph Delfau de Pontalba, became more and more involved in the marriage, easily overruling his weak-willed son. Unhappy with Micaela’s $40,000 dowry (more than $800,000 today), the Baron began a campaign of cruelty toward his daughter-in-law, which caused the epileptic Micaela to have seizures nearly every day from the stress.

The Baron wanted the entirety of the Almonester fortune and forced Micaela to sign a general Power of Attorney over to Celestin. This would allow the old man access to all her assets and capital. With the death of her mother in 1825, Micaela became sole heir to her father’s fortune, and the Baron immediately demanded she sign over all rights to the new assets in exchange for allowing her to reside in her deceased mother’s house in Paris. Micaela refused and returned to New Orleans in 1830 for an extended stay.

Upon her return to France, the Baron accused her of having abandoned her husband and attempted to keep her at the chateau permanently. Micaela retaliated by filing the first of a dozen divorce petitions asking to be free of Celestin and his father. Due to the strict marriage laws in France, each one of these was denied over a 20-year period.

In France at that time, if a woman left her husband, he was entitled to all her property and could deny access to their children. Micaela had already buried two of her five children so the Pontalba’s had a stronghold on her. Still, Micaela refused to hand total control of her assets to the Baron.

The old man reached his breaking point on October 19, 1835. Taking a pair of dueling pistols, he broke into Micaela’s bedroom and shot her in the chest four times. Micaela’s hand was also mutilated as, out of instinct, she’d grabbed one of the pistol’s muzzles as the Baron fired. Despite having been shot at point-blank range, Micaela stumbled out of the room and was led down the stairs by a maid who’d heard the first shot. The Baron followed, but seeing his daughter-in-law unconscious on the drawing room floor, he returned to his study and took his own life.

Micaela survived the shooting but not without serious scars. Her left breast was disfigured and she lost two fingers from the bullet shattering her hand. Her recovery took several years, during which time she had padded gloves made to hide the missing fingers.

Since Baron Joseph de Pontalba had died, Celestin inherited the title, and thus Micaela turned from an attempted murder victim into the Baroness Micaela Almonester de Pontalba.

Micaela sued several times for the return of her property and assets, and after several years, she was able to reclaim her holdings and fortune. She was also granted a legal separation from her husband, although they still were not allowed to divorce.

As the French Revolution threatened to break out, Micaela took two of her sons and returned to New Orleans in 1848. She became a leader of New Orleans’ elite and fashionable high society in short order. Described at the time as “shrewd, vivacious, and business-like,” Micaela was still not without critics.

She owned much of the land around the Place d’Armes. Once fashionable, the square was now a muddy, treeless field with a public gallows at the center. She set to work tearing down the houses her mother, Louise, had built in 1801. In their place, Micaela designed and built the Pontalba Buildings, the first apartment buildings in the United States. The two multi-story red brick buildings still stand along the edges of today’s Jackson Square. Shrewd as ever, Micaela negotiated a 20-year tax exemption on the new buildings in exchange for her charitable improvement of the Place d’Armes from an eyesore into a beautiful garden.

READ MORE: Who built New Orleans? The untold story of Black blacksmiths

During the building phase of the apartments, Micaela was often seen on horseback supervising the construction, dressed in pants and boots, no less. She also climbed scaffolding to personally inspect the work. Altogether, this was most scandalous as women in pants was at best immoral and at worst illegal. She lost her friendship with General Andrew Jackson over her sartorial choices. Still, the buildings were finished at a cost of $300,000.

One of the most recognizable features of the Pontalba Buildings is their ornate ironwork railings which wrap around the entirety of the building. Looking closely at the scrollwork, it may take a moment to notice the letters A and P surrounded by a flower-like crest of iron. It’s a perfect encapsulation of the woman behind the apartments: complex, strong, and nearly hidden unless one knows where to look.

Micaela returned to France shortly after the building’s completion and died in her self-designed residence in Paris, the Hotel de Pontalba, on April 20, 1874, leaving behind a legacy that spans two continents and defies belief.

Today the Hotel de Pontalba serves as the home of the American Ambassador to France.

The Baroness and the Nightingale

No one knows exactly what Micaela and Jenny spoke about upon their meeting. Perhaps it was only general pleasantries before taking care of business? Perhaps they bonded over their unusual lives? Either way, these two women were able to meet only because of their equally extraordinary talents and their will to survive even the harshest circumstances.