Editor’s note: This is a two-part story about Ajax Jones, an African American man from the Hill District who served as messenger under nice different mayors, and who briefly held the title of Mayor during a transition in 1901. Be sure to check out part 2 of the story for more about his life in city hall.

I first learned of the man who was once known as “Mayor” Ajax while researching the death of my great-great-grandmother, Lucy-Caves Robinson. She was buried in the same graveyard, alongside this “great man in Pittsburgh’s history.” It is special to have a connection to “Mayor” Ajax. I’m grateful to know more about him and I will ensure that others know him, too.

Rev. Charles Avery: local entrepreneur & abolitionist

Most history buffs in Pittsburgh have heard of a wealthy entrepreneur and ardent abolitionist, the Rev. Charles Avery. For those who have not, let me give you a quick history lesson. Picture it…Pittsburgh 1849. The area’s three rivers, its close proximity to Canada (three days by foot), and the 1780 Gradual Abolition of Slavery Act made an antebellum Western Pennsylvania especially attractive to runaways, slave hunters, and anti-slavery activists. A battle over the institution of slavery is being fought fiercely on both sides. Rev. Avery’s cotton mill business took him on buying trips to the South, where he was drawn to the plight of the enslaved. Joining the Allegheny County antislavery forces, he aided the escape of enslaved men, women and children to freedom on the “Underground Railroad.” In March of 1849, he founded a vocational school for colored youth as well as a Methodist church. The three-story building had a tunnel in its basement leading to an old canal, where runaways could be picked up by boat at the Allegheny River. Out of the five famous local Underground Railroad agents of Avery, Woodson, Delany, Peck, and Vashon – Avery was the only one who was white.

Charles Avery Jones born in 1850 in Arthursville (now known as the Hill District)

But, there is another Charles Avery recorded in the annals of Pittsburgh’s history. Charles Avery Jones was born to Sarah and “Big” Charles in August of 1850, at a time when that part of the Hill District was known as Arthursville. “Little” Charles was obviously given his first name from his father, but his middle name undoubtedly came from the abolitionist, Avery. The community that young Charles grew up in was a place where the Black working class and business elite were united and politically savvy. This community was a prosperous, lush mecca for the city’s Black population. Residents lived in handsome one- or two-story brick and frame houses. Some homeowners dug out cellars to store supplies and to hide runaways passing through on the Underground Railroad. When the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed, it caused a great panic among Pittsburgh’s Black community. On the evening of Sept. 28, 1850, a large crowd gathered around Rev. Charles Avery to protest the bad news. They pledged to oppose the “sinful” law with all their might. Approximately 706 fugitives and/or free blacks left the county within the next decade. Allegheny County’s Black population was 3,431 in 1850, dropping to just 2,725 by 1860.

“Big” Charles was more than likely involved in the anti-slavery movement. He was a barber in abolitionist centered Arthursville. There were other abolitionist Underground Railroad conductors employed as barbers who lived there, including the Rev. Lewis Woodson, John C. Peck and Benjamin Tucker Tanner. The importance of barbershops in African American communities at this time, held nearly as much importance as churches did. Many barbers were also clergymen. Barbering has always been a respected profession by every class in society. “Big” Charles once had a personal estate value of $200. Doesn’t sound like much, huh? A couple of hundred bucks in 1860 would be like walking around with $6,276.48 in your pocket in today. “Little” Charles grew up hanging in and around his father’s barbershop. He listened, he watched, and he learned. It was a space where African American men interacted with each other, regardless of age, class, education or occupation. Scattered inside and out were men playing chess, playing cards, or reading newspapers. Jones’ Barbershop acted as a backbone of the community and helped to strengthen Black male identity.

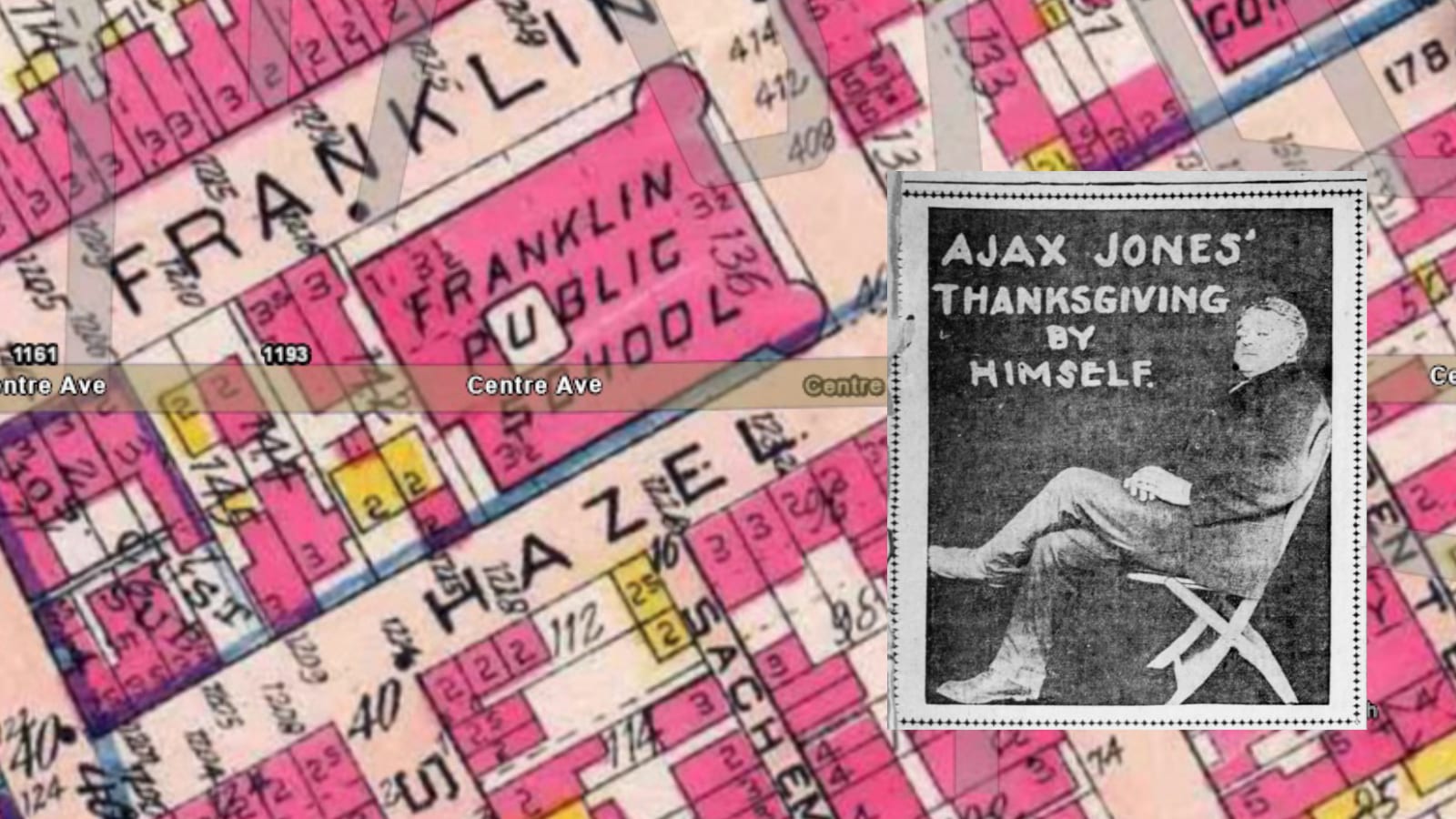

From Franklin Public School to City Hall

“Little” Charles was always a lover of books. He excelled at the Franklin street school but often got into trouble for talking too much. One day he came across a book about Greek mythology and the tragedy of “Ajax,” who was a strong and brave Trojan warrior. “Little” Charles was so inspired by the warrior’s fearlessness, he decided to call himself “Ajax,” too. That fearless spirit would carry him all the way through public and private school. He developed a bombastic speaking voice as a young man. Ajax was very well-read and always up for a debate. He was tall and broad-shouldered with a commanding presence. His big grinning smile, olive-tinted complexion and trademark curly hair was unmistakable. He developed a distinct and eloquent speaking voice. Ajax’s words filled the room and resonated deeply with his growing group of followers, especially the ladies. He often quoted poetry, the most delicate verses of prose, all of Shakespeare’s works, in addition to a multitude of other literary classics.

Ajax Jones attended Franklin Street School, which was located at the corner of Franklin and Logan Streets, just about where the PPG Paints arena sits today. His classmates at Franklin Street were William J. Diehl and Andrew Fulton. Both of these men would go on to serve as mayor.

As Ajax entered his 20s, he was already becoming a popular public speaker. He was wise beyond his years and poised for success. Ajax was ready for the world, but was the world ready for him?

See Part 2 of the story to learn more about how Ajax Jones served as the first African American mayor in Pittsburgh.

📸 Header photo: 1910 map of Franklin Public School in the Hill District over a present-day map from Historic Pittsburgh Maps and “Thanksgiving By Himself” – November 22, 1903 (The Pittsburgh Press). You can she a photo of the Franklin Public School from 1917 here.