Co-authored by Michael DeMocker

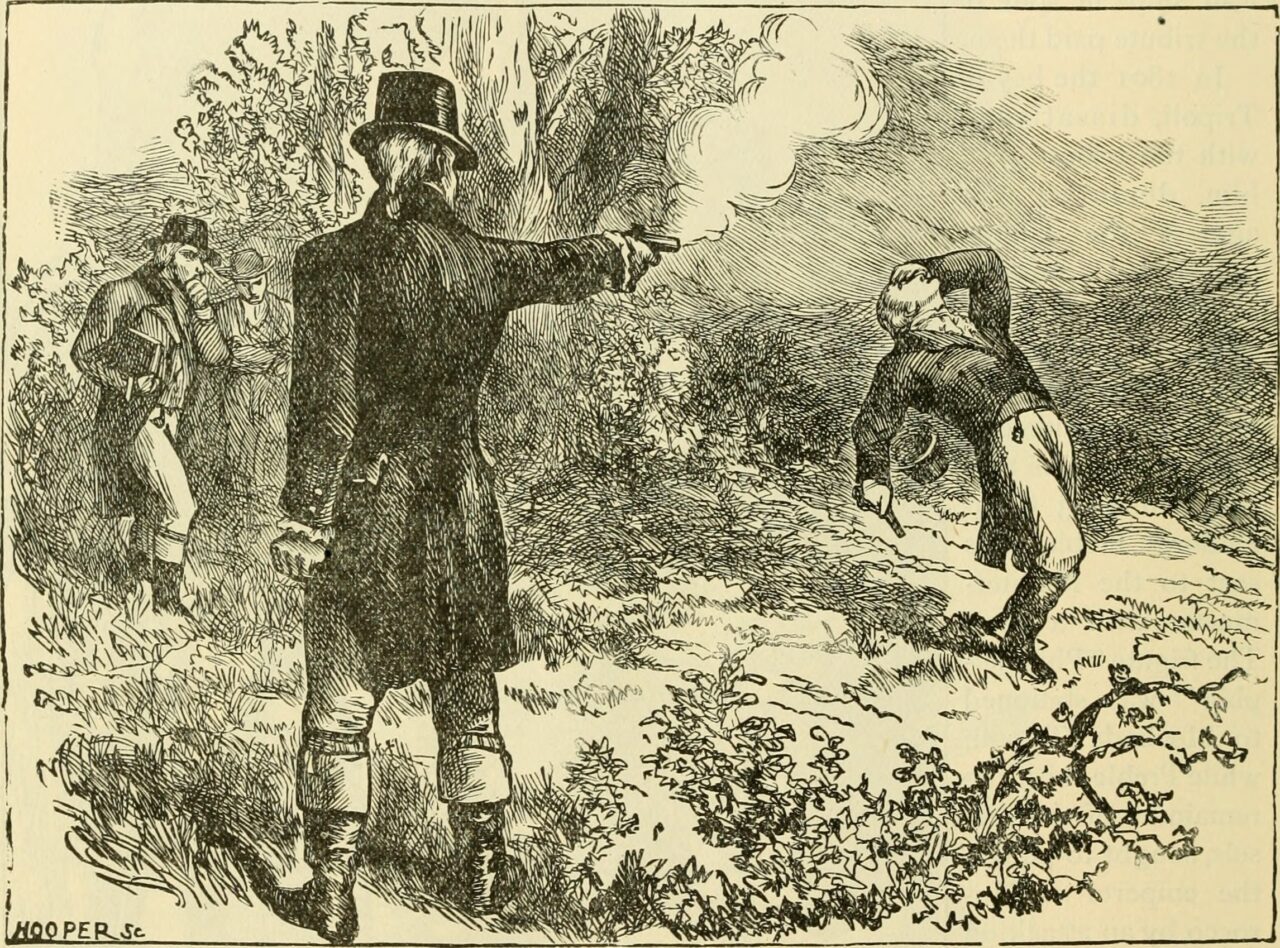

Anyone who has taken an American history class or caught the Broadway show “Hamilton” is familiar with the 1804 duel between Vice President Aaron Burr and Founding Father Alexander Hamilton. But while the shoot-out that resulted in Burr’s victory and Hamilton’s death (and musical resurrection) is a famous event, Burr’s subsequent trip down to New Orleans to possibly steal the city, Louisiana and territories in the Southwest and Mexico are not as widely known.

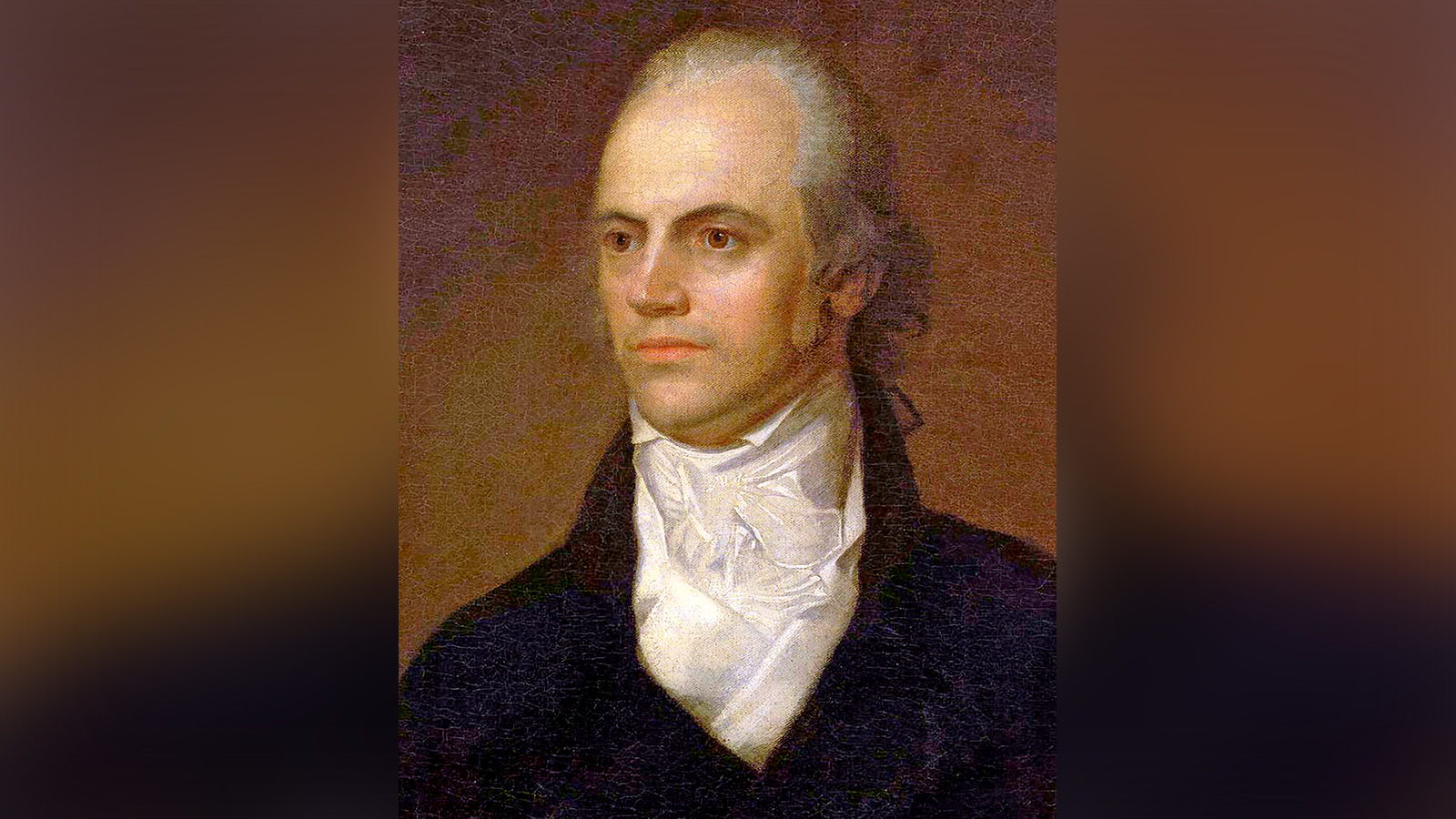

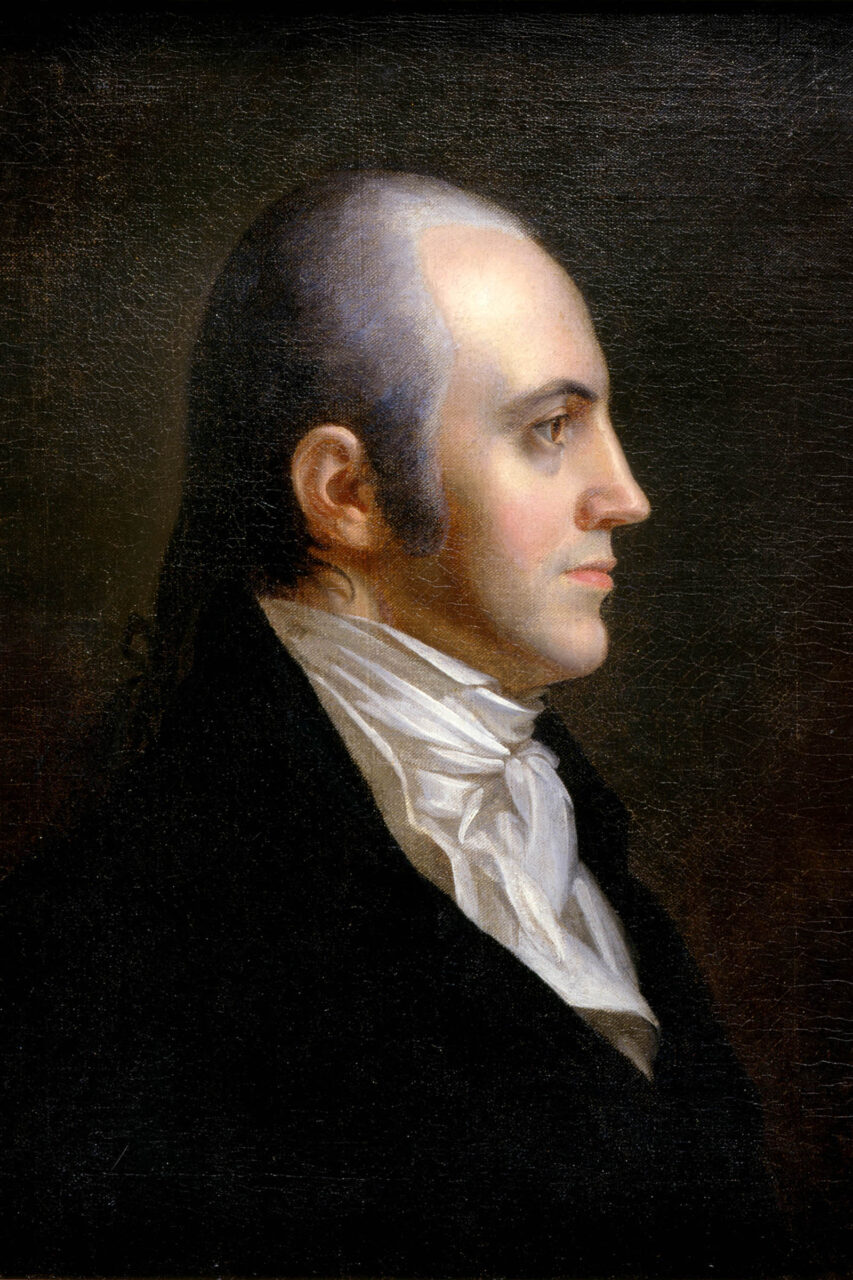

Who was Aaron Burr?

Aaron Burr was a fascinating character; accepted to Princeton at the age of 13 (didn’t hurt that his dad was running the place), he graduated at 16 and went on to serve under the soon-to-be notorious Benedict Arnold and then for George Washington himself. Burr was good at annoying powerful people and Washington was no exception; their relationship would sour in the years after the American Revolution as they discovered they really didn’t like each other much. Burr went on to found the Manhattan Company which eventually morphed into JP Morgan, helped Tennessee achieve statehood, and was elected as Thomas Jefferson’s vice president in 1800. When Burr ran for governor of New York a few years later, longtime rival Alexander Hamilton talked some 19th-century smack about him that ended up in the press, leading to the famous New Jersey duel of July 11, 1804.

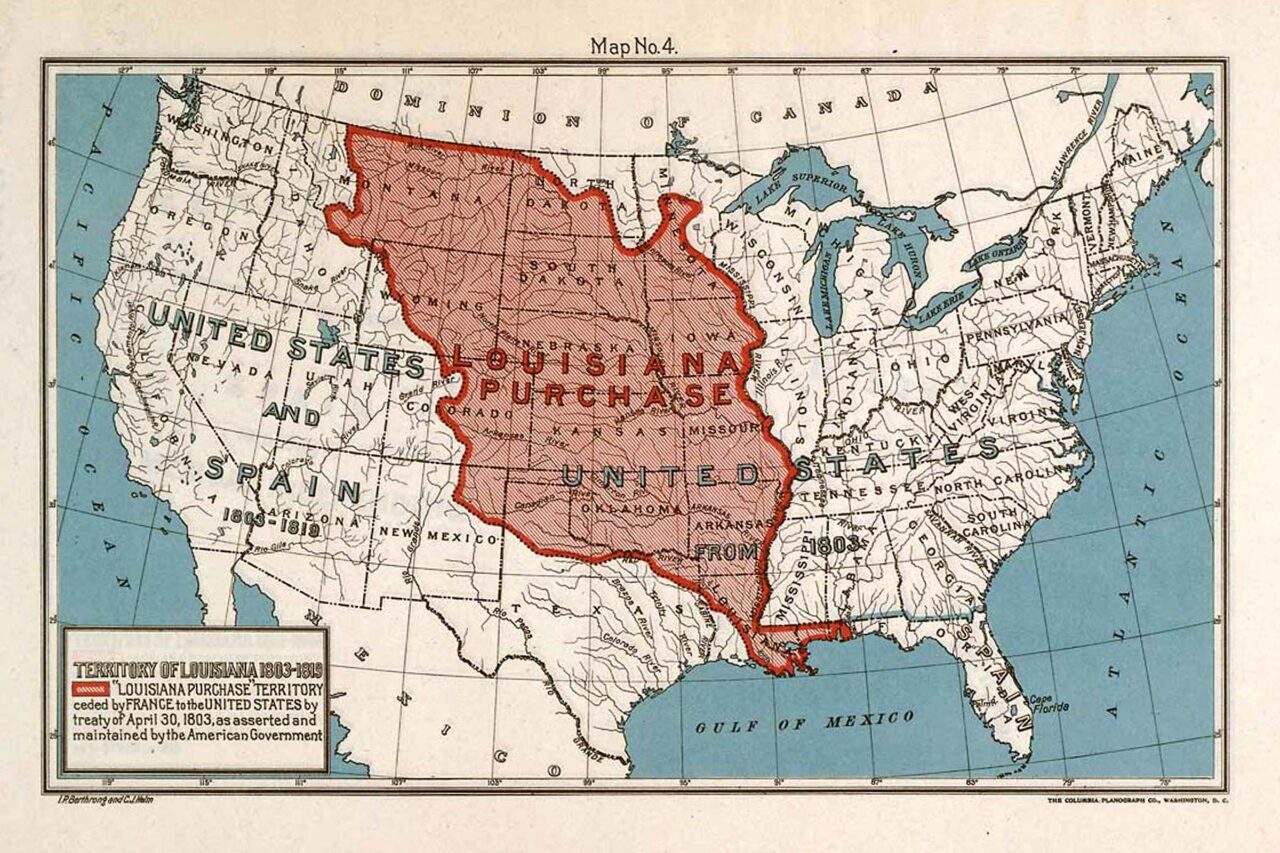

After mortally wounding Hamilton, Burr reportedly went home for a hearty breakfast but soon found himself fleeing from murder charges in both the states of New York and New Jersey. The year following his killing of Hamilton, Burr’s political career was in tatters but his fiery ambition remained. He turned his attention to the newly acquired and largely unsettled Territory of Louisiana. Its borders were disputed by Spain, specifically, a zone near the Texas border dubbed the “Neutral Ground.” Spain set up ladders and put down picnic blankets there and claimed it was theirs.

OK, not that last part.

From New Jersey to New Orleans

In July of 1805, Burr made his way to New Orleans, part of his western tour to recruit converts to a new cause. Many of the residents of the newly acquired territory, a great number of whom lived in New Orleans, were unhappy that they had come under rule by America. While Burr’s true intentions are still a mystery, many historians believed that Burr wanted to exploit the residents’ dissatisfaction, assemble a disciplined cadre of soldiers and forcibly wrest territory from parts of Texas and Mexico and perhaps Louisiana territories as well. Rumors said Burr wanted build his own country in the west, with himself in charge of course. Others say he was simply preparing a private army for a “filibuster,” which in military terms is an unauthorized (but often winked at) military excursion into a foreign land, to capture Spanish territory in Texas and Mexico in anticipation of a looming war with Spain. Apparently, he felt his world was not wide enough.

During his two weeks in New Orleans in 1805, Burr held meetings with a group of local businessmen called the Mexico Society who supported seizing land in the West that belonged to Spain. Burr seemed to enjoy his time in New Orleans, visiting the bishop at St. Louis Cathedral and spending an hour with the Ursuline nuns. Surprised at how many residents were “living in handsome style,” Burr left New Orleans impressed, calling NOLA “cheerful, gay, and easy.”

One notable character Burr recruited to the alleged plot that came to be known as the “Burr Conspiracy” was Revolutionary War veteran General James Wilkinson. Burr wanted Wilkinson for both his experience in the military and ability to make alliances. Burr had even convinced President Jefferson to name Wilkinson as the first governor of the Louisiana Territories, the northern half of the Louisiana Purchase with the Orleans Territories, including New Orleans, making up the southern portion. Burr’s recruitment activities drew suspicion and whispers of treason, which Burr’s enemies pounced upon, hauling him into court several times, but Burr, whatever his intentions, managed to forge ahead.

The Burr Conspiracy

On Dec. 10, 1806, Aaron Burr appeared to make his move, leaving Blennerhassett Island in Ohio with several ships full of men on a trip down the Mississippi River to New Orleans. News of Burr’s pending arrival sparked confusion and panic in the Big Easy; a rumor flew around that Burr was conspiring with the Creoles to confiscate all the money in the banks. (In reality, outside of an 1805 dinner party thrown by French merchants in honor of Burr’s arrival, the Creole community managed to keep out of Burr’s intrigues.) Military engineers arrived to repair the fort in New Orleans in anticipation of Burr’s invasion of the city. For the next few weeks, New Orleans was “the most complete scene of confusion and alarm I ever beheld,” said a recent arrival. Scores of soldiers and militiamen headed to the defense of New Orleans. The city stopped all commercial shipping, ensuring there would be sailors to man vessels for the city’s defense when Burr and his floating army arrived.

What Aaron Burr probably didn’t know is that his co-conspirator Wilkinson had gotten cold feet and was also, by the way, a Spanish spy. (Years after Wilkinson’s death, Louisiana historian Charles Gayarré proved this using extensive records of the governor’s treachery found in Madrid archives.) Wilkinson had come to believe Burr’s plans were doomed to failure and, wishing to save himself from punishment as a co-conspirator, wrote damning letters to his Spanish handlers and to President Jefferson in late October, outlining the conspiracy. Wilkinson claimed to have come into possession of a coded letter from Burr outlining his plan to sail to New Orleans with his army to meet up with the British Navy and carry out their invasion of Spanish territory. It is not known if Burr was the actual author of the so-called “cipher letter.” Some have accused Wilkerson of fabricating Burr’s intentions to seize New Orleans to mask his own complicity in the planned filibuster to the Spanish territories.

As New Orleans was gripped with fears of the Burr invasion, Wilkinson orchestrated mass arrests of Burr supporters he thought could connect him to the conspiracy, even placing the city under martial law. He further panicked residents by telling them Burr was now leading an army of 7,000 rebels to ransack New Orleans. The Orleans Gazette wrote on Jan. 2 that Burr now had 12,000 soldiers headed their way. A few days later, the entire Battalion of Orleans volunteers was conscripted into the federal defense of New Orleans.

Wilkinson’s heavy-handed tactics of mass arrests and martial law in New Orleans eventually led to his removal as territorial governor. But the damage to Burr’s reputation was done; President Jefferson, happy for the opportunity to smack down the overly ambitious Burr, had issued a proclamation that in essence accused Burr of treason. Burr was shown a New Orleans newspaper while traveling south which carried President Jefferson’s call for his arrest and Burr knew whatever he was planning had been scuttled. Burr negotiated to turn himself into Mississippi authorities at Bayou Pierre in order to avoid being shipped to New Orleans and into Wilkinson’s clutches. At the time of his surrender, Burr was in the company of “nine boats, and one hundred men, and the majority of these are boys” according to the acting territorial governor in Mississippi. The Orleans Gazette reported Burr had 15 boats and “not more than forty of fifty persons.” After his overblown “invasion” fell apart, Burr was eventually taken to Richmond, Virginia for trial. He was acquitted on a technicality; two witnesses are required for a conviction of treason, but only Wilkinson testified, leading some to surmise the Burr Conspiracy was completely made up by the Spanish spy. Despite winning his acquittal, Burr was persona non grata in the States and boarded a ship to exile in Europe.

Burr returned to the United States five years later, married a woman nineteen years his junior, and set up a quiet law practice in New York. By now, the conspiracy that bore his name was mostly forgotten. While he never faced punishment for his alleged plot to annex New Orleans and the surrounding territories nor face justice for killing Alexander Hamilton, karma had one last card to play: Burr’s young wife filed for divorce, employing Hamilton’s son Alexander Jr. as her divorce lawyer and he did not waste his shot. The couple’s split became final on Sept. 14, 1836, the same day Burr died.

Aaron Burr’s objectives during the mission he was leading to New Orleans may never be known; When it comes to the truth of whether he was a traitor looking to steal New Orleans or the victim of a smear campaign by his enemies, we may just have to wait for it.

Cover photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Works Consulted

Berry, Jason. City of a Million Dreams. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2018

Isenberg, Nancy. Fallen Founder: The Life of Aaron Burr. New York: Penguin Group, 2007

Jones, Terry L. “The Kingdom of Burr?” Country Roads Magazine, February 3, 2020

Lewis, James E. The Burr Conspiracy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2017

Mancini, Mark. “14 Surprising Facts About Aaron Burr.” Mental Floss, July 26, 2022

Maranzani, Barbara. “What Happened to Aaron Burr After He Killed Alexander Hamilton in a Duel?” History.com, July 11, 2022.

PBS.org. “American Experience: The Burr Conspiracy.” https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/duel-burr-conspiracy/#:~:text=Nearly%20200%20years%20later%2C%20the,Alexander%20Hamilton%20in%20a%20duel Accessed October 2022

Powell, Lawrence. The Accidental City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2012

Shafer, Ronald G., “A Former Vice President was Tried for Treason for an Insurrection Plot” Washington Post, September 26, 2022

Looking for a weekend getaway?

Watch Eat Play Stay to see more of the best spots that are an easy drive from New Orleans.

Get the Very Local channel on Roku, Amazon Fire and Apple TV to watch all of our shows for FREE.