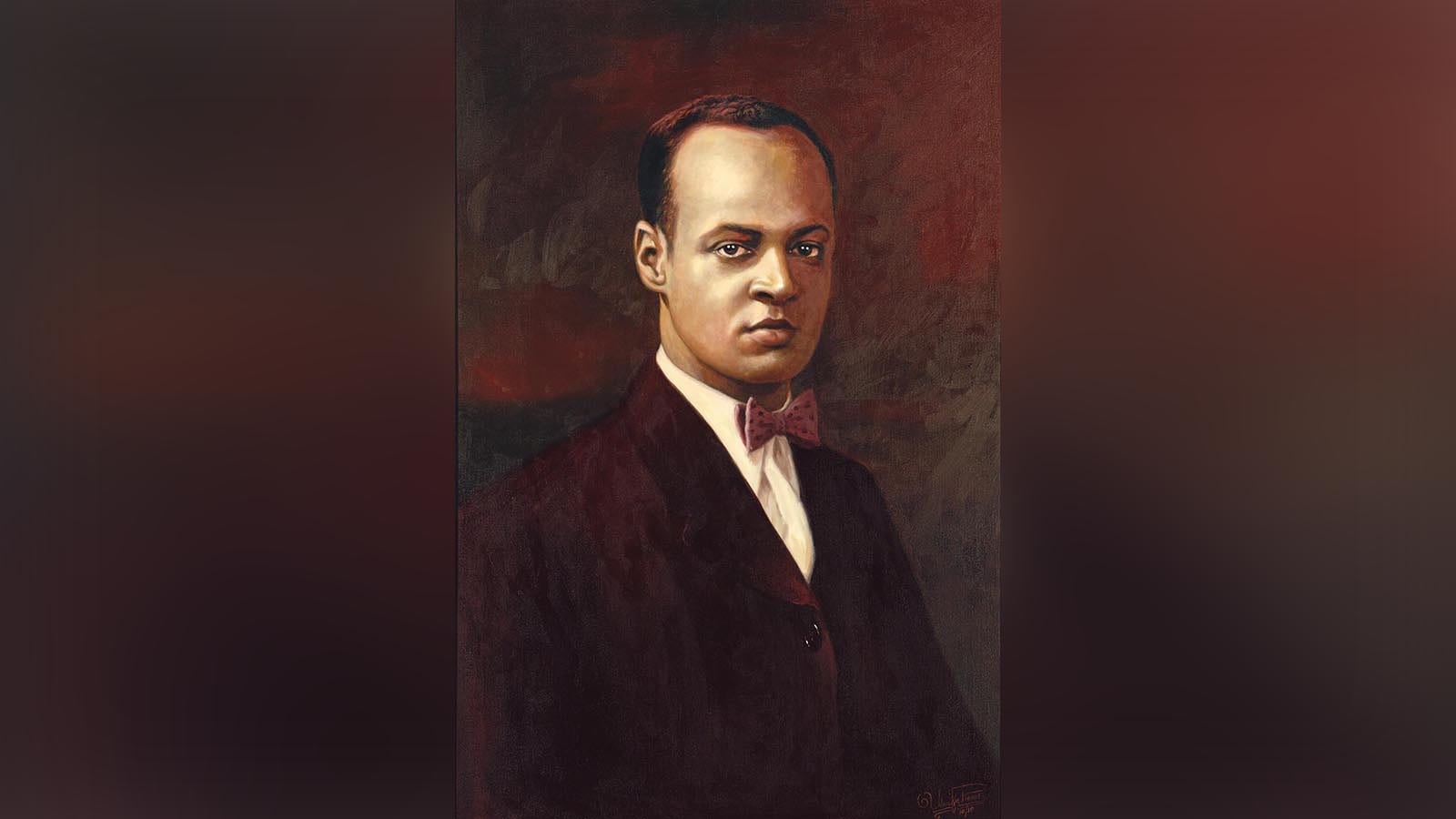

Many would call the 7th Ward one of New Orleans’ iconic Creole neighborhoods, and civil rights attorney A.P. Tureaud is one of the neighborhood’s iconic native sons. While he became widely known for his accomplished work against segregation and racial injustice, his path to success was a winding one that would ultimately call him to “right the wrongs” of the society he grew up in.

Alexander Pierre Tureaud Sr. was born on Feb. 26, 1899, just three years after the landmark Plessy v. Ferguson U.S. Supreme Court case set the “separate but equal” doctrine into law. Tureaud grew up under this system, educated in segregated New Orleans public schools, becoming the only one of his 11 siblings to finish school.

From railways to courtrooms

At 17, Tureaud moved to Chicago to work in the rail yards making $1 an hour. He then spent a year in New York City before taking a job as a junior clerk at the U.S.Department of Justice Library in Washington, DC. In 1921, Tureaud enrolled in Howard University Law School, where he met his future wife and fellow Louisianian, Lucille Dejoie. During college, he also joined Alpha Phi Alpha Fraternity, Inc and the NAACP, a move that would help shape the rest of his life.

Tureaud was eventually called back home to New Orleans to help his sick mother. In 1927, he was admitted to the Louisiana bar, making him one of four Black lawyers in the state. That same year, he became a board member of the New Orleans branch of the NAACP, which was the first branch in the Deep South.

Working for equality

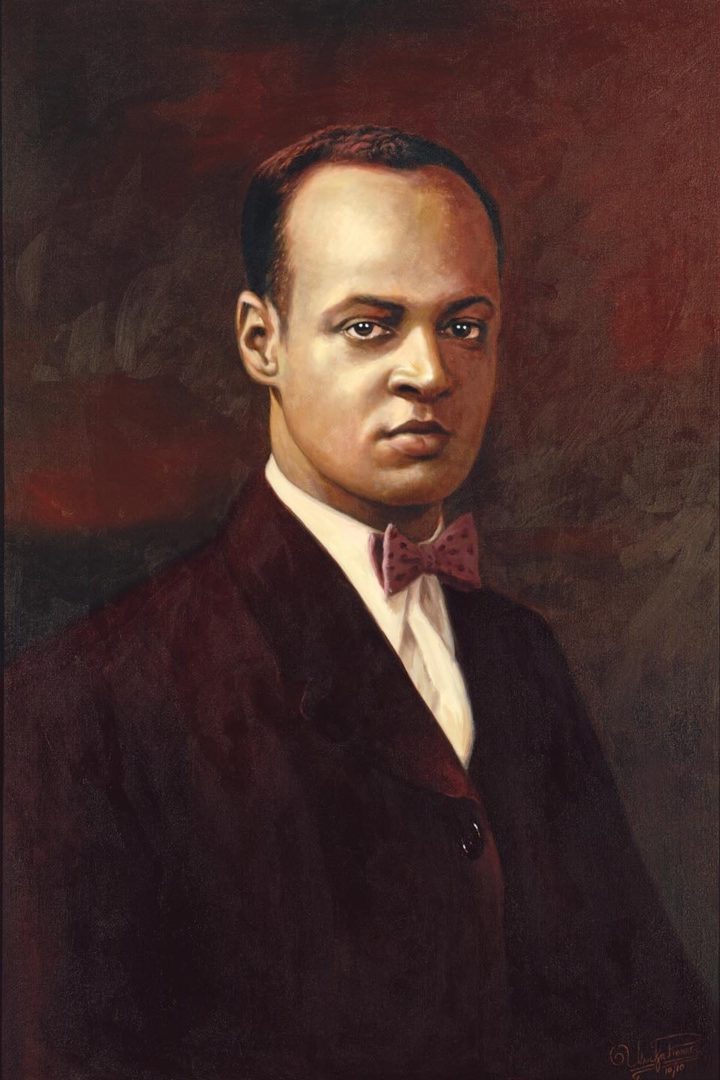

For a decade, Tureaud was the only practicing Black attorney in Louisiana. In 1941, he teamed up with Thurgood Marshall, founder of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, to challenge the pay gap between Black and white teachers in New Orleans. At the time, white teachers were making $150 a week, while Black teachers were getting paid $75 for the same work. Tureaud filed over 16 suits to get equal pay for educators. As a result of his efforts, the Louisiana state legislature adopted a minimum salary for all teachers, regardless of race, in 1948.

Photo via Amistad Research Center at Tulane University

During that same time, Tureaud and Marshall were also working to dispute voting restrictions. White registrars often denied Black citizens their right to register to vote for invalid reasons. Because of this, only 400 Black New Orleanians were registered in 1940. Tureaud himself was even turned away once for apparently making a mistake on his application.

He filed a suit to loosen the Louisiana registration procedures. By 1952, there were more than 28,000 Black voters registered in the city.

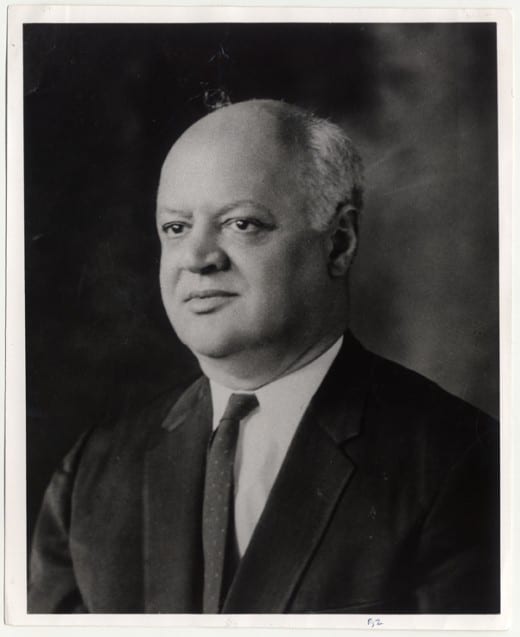

Tureaud was elected president of the New Orleans branch of the NAACP in 1952. During his time as president, he filed four lawsuits to challenge segregation at LSU’s law, medical, graduate and undergraduate schools. In fact, Tureaud’s son, A.P. Tureaud Jr., was the first Black undergraduate student admitted to the university. Tureaud Jr. enrolled in 1953, but he was kicked out later that year during a legal battle.

Clipping from the LSU Daily Reveille, 1953.

Later in his career, Tureaud fought to desegregate buses in Louisiana cities and successfully defended one of the first sit-in cases to go before the U.S. Supreme Court. He’d even go on to stage a run for Congress, which was not successful. Despite his defeat in the race, Tureaud hoped that his campaign would encourage more Black people to run for office in the future. He retired at age 70 after he was diagnosed with cancer. Tureaud died just a month shy of his 73rd birthday.

Remembering A.P. Tureaud

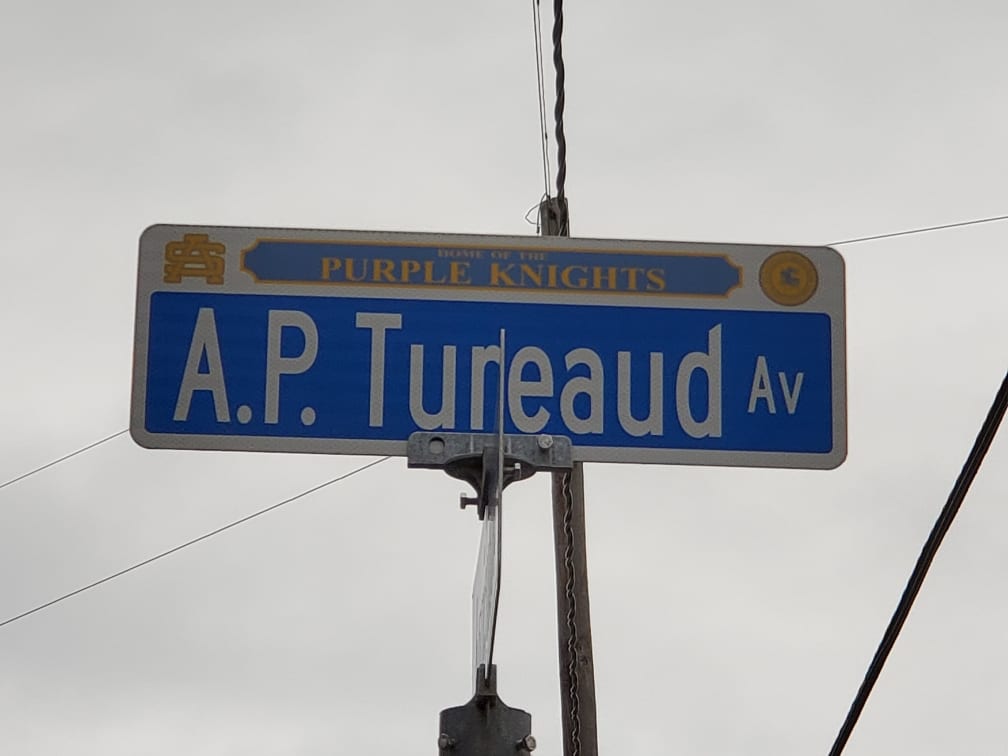

A few years after Tureaud’s death, the first Black mayor of New Orleans, Ernest “Dutch” Morial, spearheaded an effort to honor the late civil rights attorney. Tureaud was a mentor to Morial — both were 7th Ward natives. On June 6, 1981, part of London Avenue was renamed A. P. Tureaud Avenue.

Forty years later, the street in the neighborhood of Tureaud’s youth stands as a reminder of a man who broke down boundaries. A. P. Tureaud Avenue spans from St. Bernard Avenue to Broad Street, and is home to one of New Orleans’ signature Black institutions, St. Augustine High School, along with A.P. Tureaud Civil Rights Memorial Park.

SOURCES:

- “A.P. Tureaud, Legendary Louisiana Lawyer: Introduction.” LibGuides, The Law Library of Louisiana, lasc.libguides.com/c.php?g=509972.

- “Chronology.” Journey for Justice: The A.P. Tureaud Story, web.archive.org/web/20070122200625/www.lpb.org/programs/journey/chronology.html.

- “Journey for Justice: The A.P. Tureaud Story.” Louisiana Public Broadcasting, Distributed by the A.P. Tureaud Chapter of the LSU Alumni Association, 1996, www.youtube.com/watch?v=XQC8VglhiCc.