On a cool, spring Sunday morning, I jogged out of Crescent Park near the eastern end of the Bywater. The sweet smell of barbecue wafted over from The Joint as I approached a vacant plot of land bounded by France, Royal, Mazant and Chartres streets.

On that plot, there was an attractive-looking couple cuddled together on a blanket. There was a mother watching her children climb around on tree-shaded playground equipment. And there was a pair of teenage boys running football drills through the well-manicured grass.

Is this a park?

That depends on who you ask.

Google Maps makes mention of this space as Jackson St. Park — although, I’ve never heard of anyone referring to it as that.

When I first moved into the neighborhood in 2009, there were two multistory public housing buildings on this square of land. I recall biking to work one day, in 2015 or 2016, and the units had been demolished, reduced to large piles of rubble that were eventually cleared away to reveal what suddenly felt like a neighborhood park.

But, until a pair of historic markers went up approximately two years ago on the Chartres Street edge of the lot, I hadn’t realized the rich history that preceded those public housing units.

The Housing Authority of New Orleans still owns the land, and a battle is heating up around its future plans to use the property for a large, mixed-income housing development. As we consider the property’s future, I thought it would be important to look back at its past.

A palatial dwelling

David Olivier, born in Lyon, France, in 1759, moved to America in the early 1800s. We know he made his fortune on the East Coast, left Fredericksburg, Virginia in the late 1700s, and was in New Orleans by 1809.

Upon arriving, Olivier became a prominent merchant here and, in 1820, he purchased two adjacent tracts of land on which he built his home – a palatial dwelling, ornate with towering columns of white plaster brick, stately banisters, and spacious verandas. At the time of its demolition, it was the only one left in the area, but at the time it was built, it was a spectacular example of the early-19th century colonial Creole plantations common downriver of the French Quarter.

In more recent times, the mansion’s address was 4111 Chartres St., but, then, Chartres was called “Rue de Moreau.” And, what is now the Bywater, was formerly called the “lower banlieue.”

I think it’s important to note that, in the 21st century report by the Federal Emergency Management Agency, it is acknowledged that archaeologists found cultural deposits on the site that could date back as far as the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. So starting with Olivier is obviously not the true beginning of the location — only a convenient one.

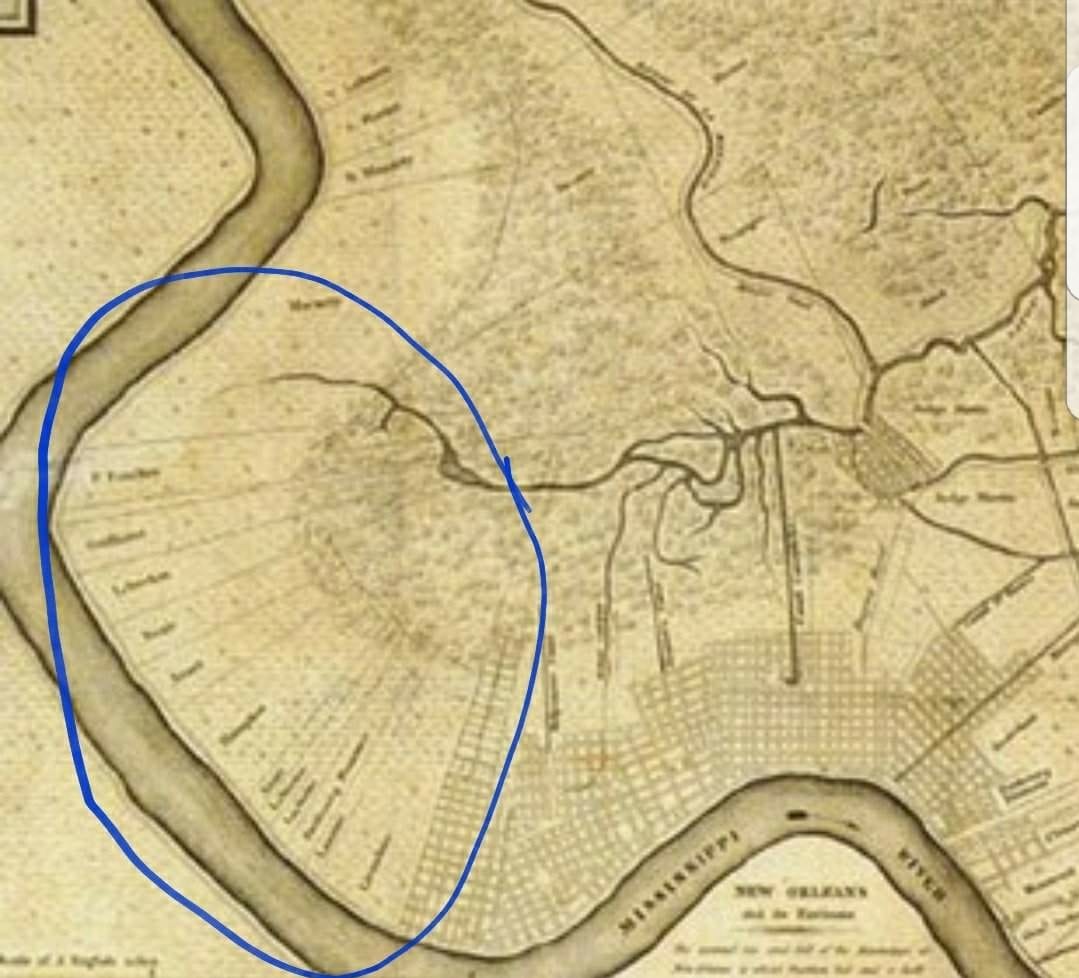

In French-influenced agricultural societies — like 19th century New Orleans outside the French Quarter — the most fertile and desirable land was near the river. It would have been unfair to give one landowner a plot next to the Mississippi River, while another received land next to to the less arable, mosquito-infested swamp, which began near present-day Claiborne Avenue. The solution common in French-influenced cities along winding rivers was to cut narrow slices of land that ran from the river and extended back. It was known as the arpent system.

Olivier’s plantation, for example, existed between present-day Bartholomew and France streets and extended back near what would become Florida Avenue. Landowners built their homes on the high ground near the river, creating what scholar Frederick Starr called, “a formidable collection of high-end Creole, French American, and American rural architecture.”

Each parcel was approximately two to four arpents wide (approximately 400 to 800 feet) and created what local historian Richard Campanella describes as “a bucolic landscape of villas with gardens, orchards, horse farms, dairies, and intensive agriculture, as well as brickyards and lumber mills interspersed with commodity plantations,” usually with slaves.

This plantation-harvested sugarcane, with pigeonniers, a kitchen, a distillery, and a stable outside the main structure. While the façade and much of the house, itself, was an excellent example of the colonial-era West Indies-influenced French Creole design, the house had a center hallway, which Campanella points out is “a privacy feature more typical of Anglo-American domestic design… and reflected New Orleans’ impending Americanization.”

(Note: a pigeonnier was used to house – you guessed it! – pigeons (and doves), which were an important food source for western Europeans, who also kept pigeon eggs, as well as their – you probably didn’t guess it! – flesh and dung.)

The home was owned by Olivier until April 1833. By this time, landowners across the city were realizing they could make more money subdividing their large parcels into neighborhoods for an exploding population than they could harvesting sugarcane. It was with this purpose in mind that Etienne Carraby and two of his partners purchased the property from its founder for $70,000.

Carraby and his partners subdivided and sold the land, but kept the house intact. There was a short span of time where a prison was almost built on the neighboring plot, and I’m not too bummed that never came to pass. Then, just a few months after being purchased, the house — along with the now much-smaller plot of land to which it was attached to — was sold to A.L. Boimare.

In 1835, the land — though not the main house — was sold to the Catholic Orphans Association, signaling the next chapter in this land’s history.

St. Mary’s Orphan Asylum

St. Mary’s Orphan Asylum, a program of the Catholic Orphans Association was founded in 1835, on Bayou St. John, by Rev. Adam Kindelon. Kindelon was the first pastor of New Orleans’ St. Patrick’s Church.

In the orphanage’s first years, a storm ripped through the Gulf of Mexico and caused Lake Pontchartrain to overflow its banks. Father Kindelon woke up to water rushing into his room at midnight. With the help of servants and teachers, the priest woke all the boys and moved them to safety. (Don’t worry, the girls weren’t left to die. St. Mary’s was a boys’-only orphanage.)

After the children were safe, Kindelon took servants to rescue the cows he used to provide milk for the boys. While he was able to rescue the animals, he had waded and swam so much that he got the chills, then typhoid, which killed him a few days later.

Yikes. Such was the beginning of St. Mary’s Orphanage.

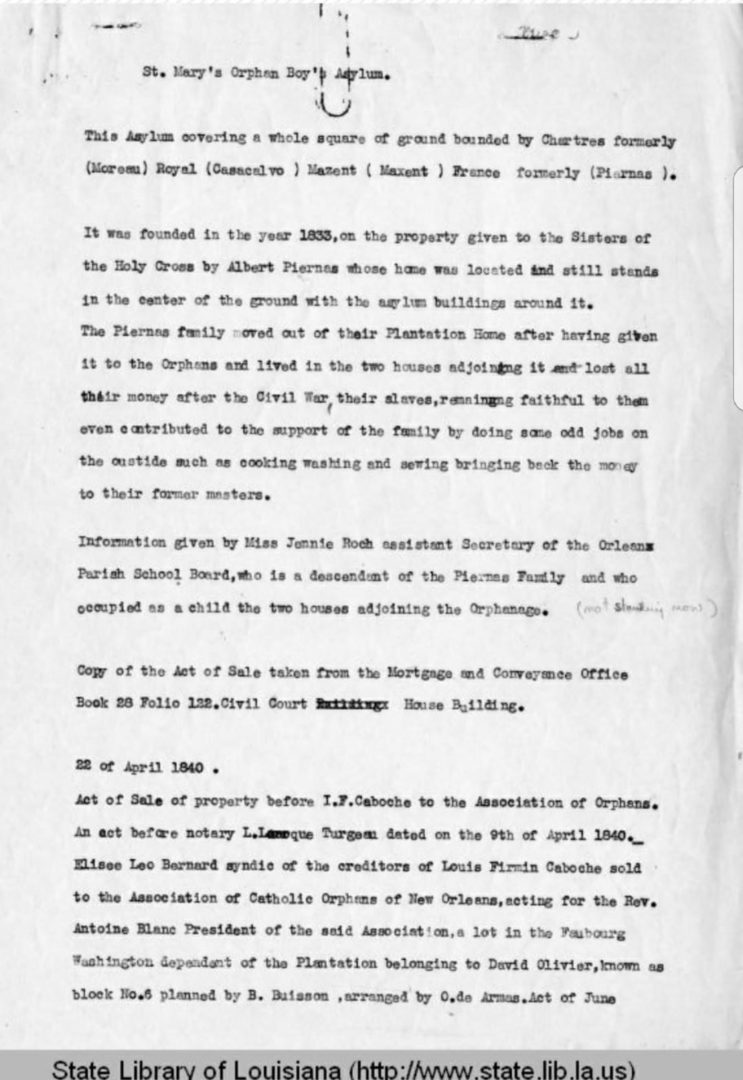

The asylum (back then, the word “asylum” was used as we use “orphanage” now) moved to a Bywater square of land on Chartres Street in 1840. It remained a part of the Catholic Orphans Association, but for much of the 1840s, it was administered by a secular group of tutors. It has been reported that during this time, the Catholics considered dropping the program, but the need for it was deemed too great. This would become even truer in the coming decades.

In 1848, the Brothers and Marianites of Holy Cross took over control of the care of the boys, and in 1953, the famous architect, Henry Howard, designed addition buildings to be erected around the edge of the property. By this point, Albert Piernas owned the main house, now mostly hidden from public view, and lived in it with his family. The Civil War, however, sent Piernas into financial ruin, and he was forced to part with the house, which he sold to the orphanage.

The extra space was needed. The cholera epidemic of 1852, the yellow fever epidemic of 1853, the Civil War, and World War I ensured. Sadly, there was never a shortage of orphans in New Orleans. St. Mary’s became the biggest orphanage in the city, usually housing between 300 – 400 boys at any given time. By the time St. Mary’s changed names and moved elsewhere in 1933, an estimated 9,000 children – infants to 15 years of age – had been served on this plot of land that now gets confused for a park.

The mansion starts a movement

But the ‘ol Olivier (‘ol-ivier) House wasn’t done yet. A 1939 book by the Works Progress Administration reports, “The building, which is now occupied by an old lady and two children who migrated to the refuge from Pointe Coupee, is surrounded by new but deserted brick buildings, and can hardly be seen from the street.” As late as 1943, the first floor of the house was the sawdust-filled Giordano Furniture Manufacturing Co.

Then, a 1949 article in The Times-Picayune described a contraption fastened around the house, “and a heavy tractor about to pull away, leveling the ancient mansion to rubble.” It goes on to describe an interested historian who happened to be walking by “almost like the square-jawed hero of a movie melodrama, he flung himself on the contractor and begged a reprieve for the house on Chartres, last example of the New Orleans riverside plantation of the early 1800s.” Amazingly, a short reprieve was granted.

Martha Robinson led a group of Tulane architecture students in an effort to quickly come up with a plan to save the structure, the last remaining example of this style of home that once was so common between Elysian Fields Avenue and Chalmette. Their plan was to document the floor plans, dismantle the house, and then reassemble it, brick by brick, in a far corner of Audubon Park they had purchased.

Unfortunately, they had very little time to raise quite a bit of money, and they were unable to do so. The historic mansion was destroyed to make room for a brewery.

That night, however, the organization that would soon become the Louisiana Landmarks Committee met and developed a strategy to avoid the future loss of our city’s treasures. This would prove a pivotal moment in the preservation of New Orleans. The Louisiana Landmarks Committee led the charge to save Gallier Hall in the 1950s, and to defeat the proposed Riverfront Expressway in the 1960s, which would have routed a highway in the small space between the French Quarter and the Mississippi River.

Now the Louisiana Landmarks Society’s mission is to promote historic preservation through education, advocacy and operation of the Pitot House.

Present Day

So what’s going on today with the block on which the Olivier plantation used to stand? (The brewery was never built, but you should definitely check out Parleaux Beer Lab, just a block away!)

Mitch Gauthier, a Bywater resident from 1963 to 1990, said that — until about 1970 — the plot of land was occupied by the National Demolition Co. The Housing Authority of New Orleans purchased the property that decade and erected low-income and senior housing starting in the early 1970s.

By 1998, 10 multiunit public housing apartment buildings were on the lot, but — by 2003 — only two of those buildings remained near the corner of Royal and France streets. Those were the final buildings knocked down within the last half-decade, making room for what a contingent of residents feel should remain a park.

But many other residents, and the Housing Authority of New Orleans, point to the 22,000 families currently in need of housing vouchers — and the nearly 44,000 households paying more than they can afford as housing — as evidence that there are more important uses for this property.

As the debate heats up, there will be much debate about what this property should be. Some of that conversation should include a knowledge of what it has been in the past.

Writer Matt Haines lives in New Orleans. Follow him at matthaineswrites.com, and on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.