It’s likely most New Orleanians know the Union Passenger Terminal exists. But I’m not sure how many of us have actually been there. These days — much to my chagrin — airplanes and automobiles are generally more popular modes of transportation than trains and buses.

But swing by the station at any given time and you’ll see many dozens of travelers using Union Terminal as their port of entry or departure to and from our lovely Crescent City.

There are Amtrak trains connecting us to points north like Chicago and New York, and points west like Los Angeles. And there are buses — Greyhound and, now, Megabus — heading in the direction of just about anywhere in the continental United States.

Airports and highways might beat out bus and train stations as far as sheer numbers are concerned, but a visit to this landmark on the edge of Central City and the CBD can tell us a surprising amount about the city we call home!

The Golden days of rail travel

Due to the emphasis the city put on river commerce and travel — as well as the destruction of southern rail lines during the Civil War — New Orleans was late to the rail travel game.

But the city did eventually become a hub. Today, it’s the terminus for several lines of Amtrak — the quasi-public corporation which has become synonymous with U.S. train travel. But Amtrak’s dominance wasn’t always the case.

In the early 20th century, New Orleans served several rail companies, each with their own impressive station.

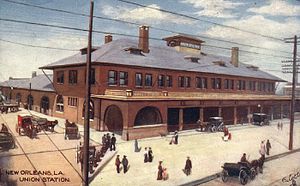

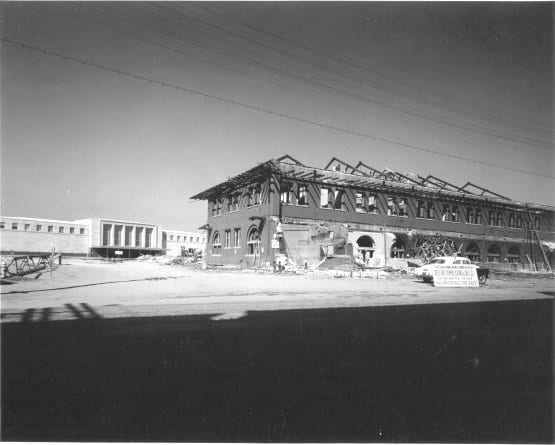

One of those companies was the Illinois Central Railroad, which opened a southern terminus for its line — which ran all the way north to Chicago — on June 1, 1892. Named “Union Station,” it was built on South Rampart Street, just in front of where the current Union Passenger Terminal would eventually be built.

But Union Station wasn’t just any train station. It’s the only station ever designed by Louis Sullivan, the Chicago architect known today as the “father of skyscrapers,” “father of modernism,” and one of the three most famous architects in American history.

His mentee, and young head draftsman on the project — Frank Lloyd Wright — was another in that future grouping of three seminal American architects, recognized by the American Institute of Architects as the greatest American architect of all time.

The building was constructed in Sullivan’s well-known “Chicago School” style, and decorated with his iconic ornamentation. The station was a three-story, hip-roofed structure with a cupola, and a broad portico with central columns and arched entryways at each end of its entrance.

But train travel wasn’t the only mode of transportation that historically converged on this location. The New Basin Canal — which, from the 1830s to the 1940s, served the traditionally Anglo-American segment of the city (as opposed to the Creole section served by the older Carondelet Canal) — flowed into its turning basin, located on the site of today’s Union Passenger Terminal.

Ships departed and arrived daily, transporting large amounts of cargo and passengers between New Orleans and points east — like Mobile, Alabama — and beyond.

In this context — as a growing center of transportation — the site’s next chapter makes a lot of sense.

Into the modern era

While the Union Terminal was built for the Illinois Central Railroad, over time, the station began to serve other lines, as well, including the Southern Pacific Railroad and the Yazoo and Mississippi Valley Railroad.

However, stations for several other lines remained scattered across the city. The Texas Pacific – Missouri Pacific Railway, for instance, was on Annunciation Street in the Irish Channel. The Louisville and Nashville Railroad Station was on Canal Street near the Mississippi River. At the time, there were five different train stations operating in different corners of New Orleans.

As vehicular traffic became more popular, the scattered nature of the city’s rail system created plenty of opportunities for problems. The Report on Proposed Railroad Grade Crossing Elimination and Terminal Improvement for New Orleans, Louisiana — written in 1944 — explained, “The city and its vehicular traffic have grown enormously and railroad facilities and operations now materially interfere with the orderly flow of vehicular traffic and are also factors impeding the local physical development of the city.”

As a result, and just four years later, the eight railroad companies that served the city agreed to consolidate into one central facility — which the city owned, but the rail lines paid for themselves.

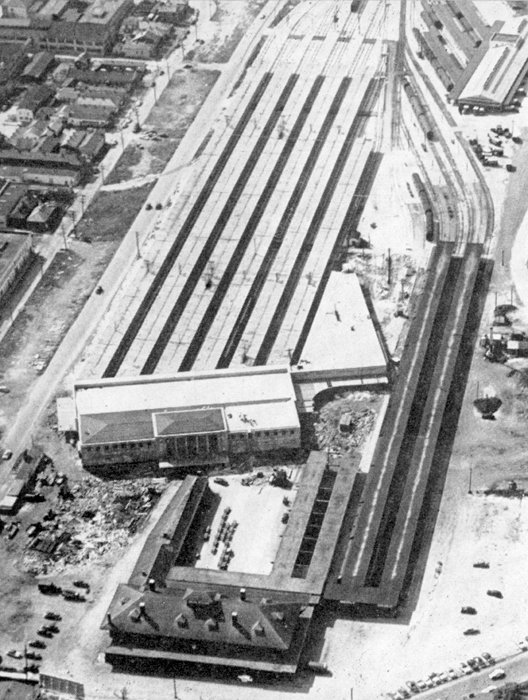

The New Orleans Union Passenger Terminal opened on Jan. 8, 1954, and was lauded as an ultra-modern facility. Built at a cost of $2,225,000, the station had stone facing, served 44 passenger trains each day, and was the only air-conditioned station in the country.

The main lead track in and out of the station follows the path of the New Basin Canal (which was filled in in the years before the new station was built).

In the late-1960s/early-1970s — as busses gained steam (ha?) — two platforms were shortened to make room for Greyhound Lines at the station. And, over the years, Amtrak took control of the passenger lines once operated by individual railway companies.

In January 2013, the station became the terminus for the Loyola Avenue streetcar line, and — in 2015 — Megabus moved its operations to the terminal.

Camp Greyhound

Unfortunately, when examining the history of most places in New Orleans, you’ll usually uncover some instance of tragedy.

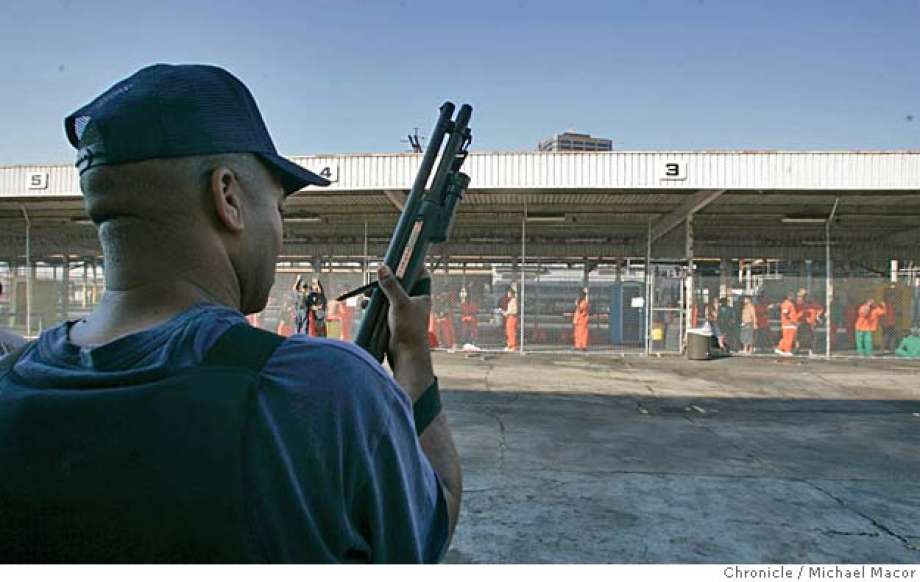

Shortly after Hurricane Katrina hit the region on Aug. 29, 2005, the Louisiana Department of Corrections made the construction of “Camp Greyhound” — the nickname given to the temporary makeshift jail outside the Union Passenger Terminal — a top priority.

Local jails had flooded, so officials quickly built 16 cages of chain-link fencing — topped with razor wire — under the canopies to hold up to 700 people. The facility opened on Sept. 5, and — with no furniture in the cages — inmates had to sleep on the asphalt ground (under full lighting because an Amtrak engine was generating power all day and night), and use an open portable toilet.

Inmates — who were most frequently being held for crimes such as looting, curfew violation, vehicle theft, intoxication or resisting arrest — were guarded by officers from the Louisiana State Penitentiary at Angola or by employees of mercenary companies. The jail had a single public defender, who could only give inmates the option to a) plead guilty and agree to community service, or b) be sent to a permanent facility and wait a minimum of 21 days for further processing.

It has been reported that approximately 1,200 people passed through the jail during the less than two weeks it was open. Regular judicial proceedings were not followed, violating habeas corpus rights. And a number of reports have emerged indicating innocent people were incarcerated for a prolonged period of time — in one case disappearing into the penal system for more than a year.

More than 300 years of history

For all the history that’s on this site, the most obvious example of New Orleans lore can be viewed inside the station, itself.

Conrad Albrizio was born in 1894, one of seven children born to Italian immigrants in New York City. He came to New Orleans several times for work as a young architect and artist, but would always end up back up north.

After furthering his studies in Rome and France, Albrizio resettled in New Orleans and received his first major commission in 1932 (as part of Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal funding): 900 square feet of wall space in the new Louisiana State Capitol building in Baton Rouge. Four years later, he joined the faculty at LSU as a professor of art.

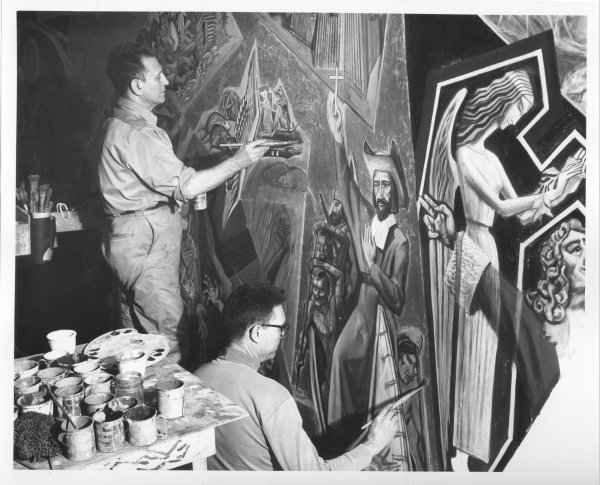

In 1951, he received a commission for his most monumental project. And, if you walk into the Union Passenger Terminal today, you’ll still see his work: a 2,166 square-foot mural that shows 400 years of history in New Orleans, wrapping around the interior of the station.

Photograph by Leon Trice. New Orleans Railroad Terminal Board Series, Municipal Government Photograph Collection.

In Europe, Albrizio learned the technique of creating frescos like the ones you see in this station, where the paint is applied directly to a wall’s wet plaster.

But the technique isn’t the most unique component of his work. At a glance, it isn’t the subject matter either. After all, it’s not unusual to see murals depicting local history when you travel to a new city. Look closer, and you’ll see what is unusual: the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse watching over the dead and injured on a Civil War battlefield; or — for another example — what appear to be ghosts flying down to carry away victims of disease.

And, trust me, this is just the tip of the very bizarre iceberg Albrizio has created.

He’s split the work into four segments — Exploration, Colonization, Struggle, and Modern Life — that all get more weird the longer you look at them. Phantom images of wealth lure explorers to their death. A worm eats through corn and leaves behind a trail of rot. Skeletal figures — presumably dying of yellow fever — hover nearby cheerful carnivalgoers.

And…so…much…more…

It’s strange. It’s gruesome. It’s history. And it’s extraordinary to look at.

Whether or not you have a train or bus ticket leaving from the terminal, a visit to these amazing murals inside the Union Passenger Terminal is well worth it. The events depicted in those murals — as well as the events that have taken place in and around this building — have shaped the city in which we live.

A visit here is a great (and free!) way to get in touch with that history.

Writer Matt Haines Lives In New Orleans. Follow him at Matthaineswrites.Com, and on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter.