For more than 40 years, Fred Parker was the face of Santa Clause for Black New Orleanians. Now, part of that magic is gone.

News of Parker’s death spread Saturday night, sending residents to social media with their posts paying homage to him.

You aren’t from #NOLA if you don’t have a photo with #7thWardSanta .lolol 🤷🏾♀️ I really use to make my #ChristmasList with this guy in mind as a child. ❤️❤️ prayers up for the family of Fred Parker🙏🏽 #RIPChocolateSanta pic.twitter.com/rwyg6boDFe

— Shay O’Connor (@SOCONNORNEWS) August 25, 2020

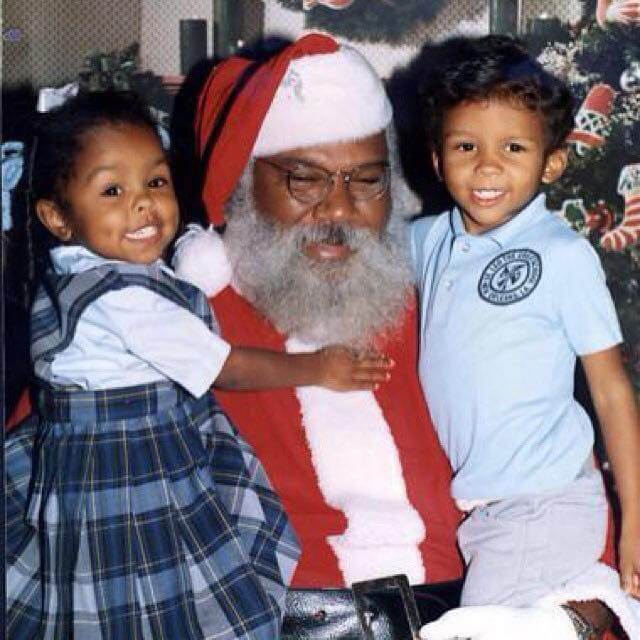

Angie Dyer, a native New Orleanian, said her first picture with Chocolate Santa was when she was about 3 years old.

“He used to be a bus driver for the school board, and my mom worked for the school board and that’s how she met him,” Dyer said. “My mom would have these parties at her house and Santa would come and it was always Mr. Fred. He would come in through our back door that led to the living room, because we didn’t have a chimney. I went my entire life knowing that Santa Clause was Black.”

Dyer said that pictures with Parker tied families together for generations.

“My cousin who is a few years older than me, she has a picture with Black Santa and so does her daughter,” she said. “The fact that they look exactly the same in these photos, it goes across those lines as well.”

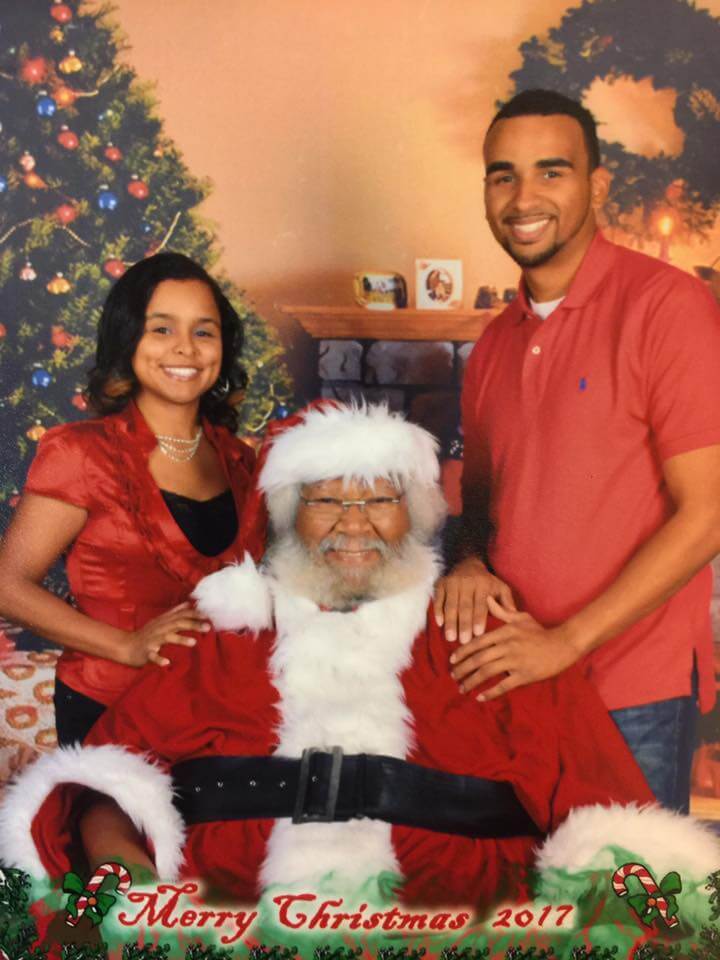

While Hurricane Katrina may have taken many of our childhood photos, 7th Ward Santa was something that was here well before Katrina, and lasted beyond the storm. Unlike second lines or Super Sundays, which have become more mainstream (for lack of a better word) since the storm, 7th Ward Santa was something that was always ours.

“In a time and space where things are constantly being taken away from us, watered down and distorted, sort of erased from our generational culture, I’m really glad Black Santa was a staple and didn’t get caught up in the rapture of gentrification,” Dyer said. “I think especially in this city, because we’re such an old city, there are so many things that are tied to generations upon generations. I think it’s really important especially with Black Santa, it’s sort of a mythical thing. Without him, we’d just be floating in this world where we think that Santa Clause is this jolly white man with rosy cheeks and we would have that same narrative. But to know there’s a different narrative for Black New Orleanians, to have our own story, and our own sort of piece of cultural society that’s ours. I have white coworkers who have never heard of Chocolate Santa before until I would bring it up. It’s amazing how you can go years and live in the same city and have different experiences in New Orleans.”

I asked Dyer to walk me through the first minute after she heard Parker had passed.

“My roommate saw it on Twitter and she was like, ‘Oh my God, Chocolate Santa passed away,’ and immediately she was like, ‘But you know they say that every year,'” Dyer recalled. “There’s just certain people that are ridiculously immortal that when rumors come about of them passing, I won’t believe it until family members confirm it or it’s a real thing.”

Then, Parker’s family members began announcing his death on social media networks.

“I saw one of his family members post it on Facebook and I was just like, ‘Oh no.’ I was in denial for a second,” she said. “The first thing I thought about was the children who will never get a chance to know him in real life.”

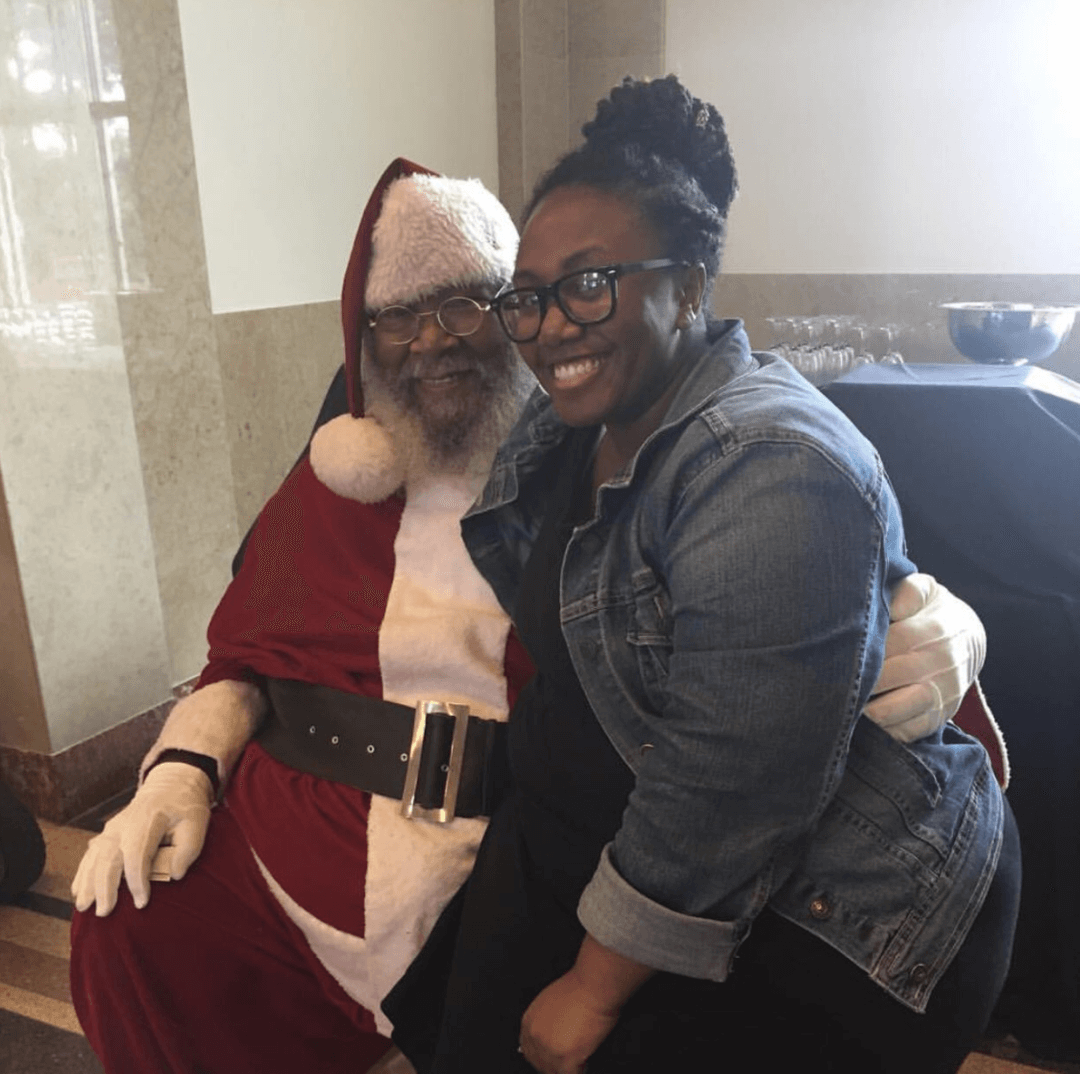

But she added there’s celebration in grief.

“I also got a little bit of joy knowing that they’ll sort of have these folklore tales of Chocolate Santa that once lived in the 7th Ward, and we knew him, and he loved us. He knew mom and all of these different people. It’s one of these things where I find great joy in the grief of his passing because at least his story will live on. And our photos with him, we’re going to get them in really nice frames and put them in our houses and tell our kids, ‘Yeah, I told you Santa Clause was Black.’ It’s going to live on for generations to come.”